Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program sets sights on Lake Ontario

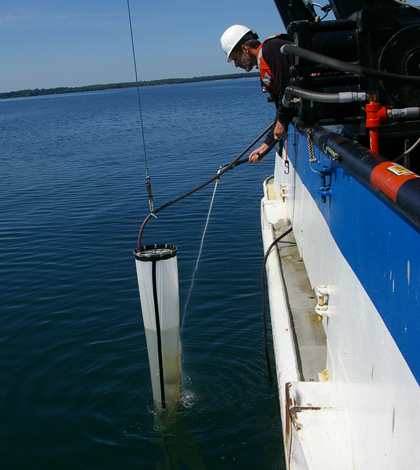

Researchers aboard the EPA's R/V Lake Guardian sample plankton as part of the Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program (Credit: Michael Milligan)

Combating pollution in the Great Lakes has been a priority for scientists over the past few decades. However, the battle continues to be an uphill climb. Just as researchers start to understand the impact of past pollutants in the lakes, new sources of contaminants inevitably pop up.

Nonetheless, the continuous need to monitor water quality in the Great Lakes hasn’t deterred researchers from Clarkson University, the State University of New York at Oswego and the State University of New York at Fredonia to continue the fight of trying to understand how pollution is affecting the Great Lakes.

In 2011, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency awarded Clarkson University a $6.5 million grant to conduct the Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program. The program, which is part of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, is in the third year of a scheduled five-year research period. As part of the project, researchers focus their study on one of the Great Lakes per year. The team studied Lake Superior in 2011 and Lake Huron in 2012

Earlier this summer, the researchers boarded the Lake Guardian, an EPA research vessel, to study Lake Ontario for four days.

The team tested the lake for pesticides, PCBs, mercury and a host of other contaminants using air samplers from Tisch Environmental, Inc., specially designed water samplers constructed by Clarkson University and an EPA-designed benthic sled, which was dragged behind the research vessel to collect surface sediment.

The researchers also collected phytoplankton, zooplankton and mussels. In addition, the researchers will study forage fish provided by the U.S. Geological Survey to examine how pollutants are accumulating in the lake’s organisms.

Although the results of the Lake Ontario study won’t be known until researchers analyze samples in the lab, the scientists are looking to previous studies to try to understand how certain pollutants accumulate within the Great Lakes food chain.

According to researchers, preliminary findings on mercury levels in the great lakes mirror what is happening in lakes throughout the world: Mercury levels are low in organisms at the bottom of the food chain (like zooplankton), however, levels increase dramatically towards the higher end of the food chain. Additionally, as mercury accumulates higher in the food chain, relatively harmless elemental mercury and other non-toxic mercury forms get converted to methylmercury–a highly toxic form of mercury.

The EPA’s R/V Lake Guardian carried researchers on Lake Ontario for the Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program (Credit: Michael Milligan)

Understanding how mercury bioaccumulates in Great Lakes fish is important for protecting the lakes’ wildlife as well as the people who might consume contaminated fish.

The researchers are also interested in how emerging and legacy contaminants are affecting the Great Lakes. Emerging contaminants are pollutants such as personal care products, pharmaceuticals, flame retardants and other industrial chemicals that wastewater treatment plants have a difficult time effectively processing. Legacy contaminants are pollutants such as PCBs and DDT that still exist in the Great Lakes even though their use was banned in the 1970s.

And while legacy contaminants are dwindling in the Great Lakes because of past regulatory action, there is still action that needs to be taken to control the influx of emerging contaminants in the Great Lakes.

“For legacy contaminants, where there aren’t sources that can be turned off, there isn’t really a lot that can be done. We are just kind of monitoring things, making sure the systems are behaving like we expect,” Clarkson Civil and Environmental Engineering Professor Thomas Holsen said. “However, for the emerging contaminants, things like flame retardants and pharmaceuticals, clearly we know the sources of those, and so if we can demonstrate that concentrations are increasing, then there can be regulatory actions.”

This is the second time researchers from Clarkson University have helped lead the Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program. Clarkson was previously awarded a five-year grant from the EPA to monitor the Great Lakes.

Top image: Researchers aboard the EPA’s R/V Lake Guardian sample plankton as part of the Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program (Credit: Michael Milligan)

0 comments