Jellyfish Database Initiative records evolving jellyfish distribution

Golden jellyfish (Mastigias) jellyfish in Jellyfish Lake, Palau (Credit: Chris Lubba)

Believed to be the world’s oldest multi-organ animal, the jellyfish has captured the fascination of both the public and scientific communities for centuries. However, relatively little is known about the relationship between these spectral creatures and the global ecosystem due to a lack of historical data.

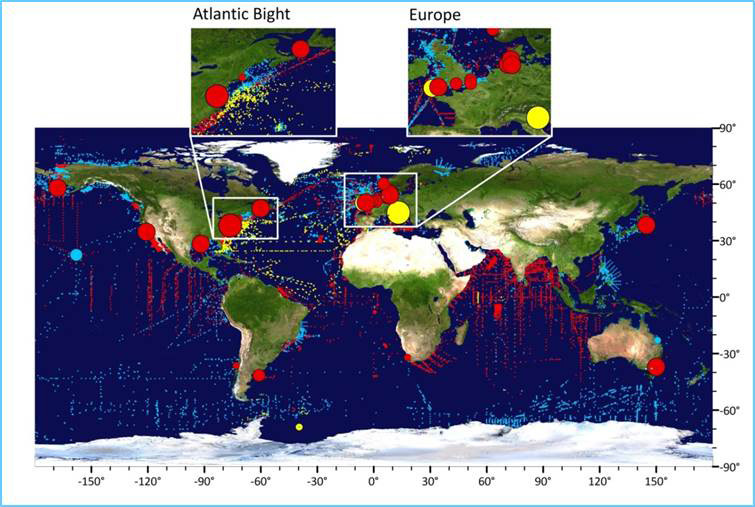

The Jellyfish Database Initiative, or JeDI, maps global jellyfish biomass, serving as an evolving record of jellyfish distribution patterns and the environmental factors that shape them. An international study led by the University of Southampton produced the database, which holds over 500,000 data items related to jellyfish.

“Up until recently, there’s been a perception of an increase in jellyfish globally,” said Robert Condon, assistant professor at University of North Carolina Wilmington. “This paradigm is based on no scientific evidence at all.”

Anecdotal evidence and a few sparse studies popularized the perception. Condon admitted that he and some of his colleagues once helped spread that notion, but a study, led by Condon and published in 2013, would set the story straight.

“About four years ago… I started a project based in Santa Barbara,” Condon said. “We found a bunch of working groups to come in and look at some big picture questions.”

These questions revolved around global jellyfish populations, and the relationship between jellyfish and environmental characteristics such as temperature and dissolved oxygen. To answer them, Condon and his team needed a way to establish a baseline dataset. The project resulted in the 2013 study, the findings of which grew into the JeDI database.

Constructed by Jim Regetz of University of California, Santa Barbara, and managed by Condon and the Global Jellyfish Group, JeDI incorporates data from resources such as ship logs, scientific studies and older datasets.

World map showing the location of jellyfish data held in the Jellyfish Database Initiative, JeDI

At the time of Condon’s study, the perceived increase in global jellyfish abundance was attributed to a decline in ocean health. Examining the dataset that would become JeDI, the researchers discovered a telling trend.

“The interesting thing that we found from synthesizing all this information is that jellyfish are not increasing globally,” Condon said. “Jellyfish are actually going through successive rise and fall periods every 20 years.”

The baseline data helped Condon establish correlations between jellyfish biomass, temperature and dissolved oxygen. He found that temperature has a positive correlation with biomass, whereas dissolved oxygen is negatively correlated with biomass. Condon stressed that this relationship isn’t necessarily the product of global climate change, but it does have global implications.

“We’re trying to identify the mechanisms that are controlling these cycles,” Condon said. “These are all unknown to science.”

While JeDI is a powerful standalone tool, it can be used to great effect in conjunction with other resources. One of Condon’s students is using JeDI to compare jelly, turtle and fish distributions. His goal, Condon said, is to identify ocean conservation “hotspots.”

As JeDI continues to grow, Condon said he would like to develop a smartphone app that allows users to upload jellyfish images and GPS data to the database. An app produced by citizen science project JellyWatch inspired the concept.

Moon jellyfish (Aurelia) beach stranding at San Francisco in November 2010 (Credit: Ocean Beach Bulletin)

But why monitor the humble jellyfish at all?

The elusive organisms play a more important part in the ecosystem than the average beachcomber might know. Jellies provide food for turtles and other fish, and help transfer carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the deep ocean. There’s a human element, too:

“From a human impact point of view, jellyfish both negatively and positively affect human activity,” Condon said. Humans depend on the ocean for fisheries, tourism and recreation, but the presence of even one box jellyfish, for instance — with venom capable of killing an adult in minutes — can halt marine activities.

“There’s potential to use this as a tool to sort of assess a particular area, and find what the impact of species ‘x’ is in that area on something like tourism,” Condon said. “People are going to be able to access all of this information.”

The open-access version of JeDI is nearing completion, and will be available to the public at the University of North Carolina Wilmington website. Until then, researchers can still request or submit data by contacting Condon.

When asked if JeDI is an intentional reference to the Star Wars film series, Condon laughed.

“No,” he said. “My wife actually came up with that.”

Top image: Golden jellyfish (Mastigias) jellyfish in Jellyfish Lake, Palau (Credit: Chris Lubba)

Pingback: Media Digest Archives | E-Voice