Monterey scientists refine phytoplankton modeling with robotic observation

Phytoplankton drifting in the ocean probably never cross one’s mind on the morning commute. However, the exhaust fumes left behind may eventually be consumed by those simple plants as part of a complex process Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute scientists study with modern technology.

The long-term study is called the Controlled, Agile and Novel Observing Network, or CANON. Scientists need all those adjectives and more than a few aquatic unmanned vehicles to keep up with phytoplankton in the ever-changing ocean.

“The most challenging thing is observing the same plankton at the same time twice in a row,” said Jim Bellingham, chief technologist of the aquarium research institute and a founder of Bluefin Robotics.

Bellingham said that unlike tracking weather and ocean currents “you don’t have an equation to show how an ecosystem changes.”

Francisco Chavez, aquarium research institute senior scientist and chief scientist of the most recent CANON mission, is trying to change that by improving models of phytoplankton in relation to the ocean’s consumption of carbon.

Chavez and a group of researchers traveled to out into in the Pacific Ocean hoping to track down phytoplankton to study. They based their coordinates on modeling and autonomous glider surveying indicated they would likely find a high concentration of ammonium, which phytoplankton consume. It worked. That alone was a great discovery, Chavez said.

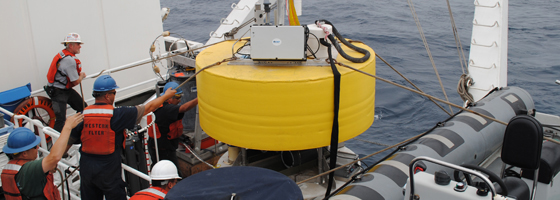

On the latest CANON mission, AUVs surrounded a submersible robotic DNA laboratory that autonomously collects samples and runs tests at multiple depths. Chavez said the submersible lab tells researchers two important things: what organisms are present and what genes are being expressed.

Gene expressions indicate portions of phytoplankton’s fast metabolic processes, Chavez said. Metabolic processes tie into a recycling loop that sustains life and consumes carbon. “As we move off shore, what tends to take over is the recycling of the organisms that are consuming the plants,” Chavez said.

Zooplankton feed on phytoplankton out in the ocean where there are few nutrients. Then, the zooplankton excrete ammonium which the phytoplankton consume. The predator sustains the prey, and vice versa.

Phytoplankton and zooplankton recycling creates a consistent passageway for carbon dioxide to enter the ocean, but it doesn’t always happen in the same place at the same time. Scientists on the recent CANON mission found ammonium turns over every five days.

Once phytoplankton die, they sink to lower layers of the ocean creating nutrients and affecting ocean acidity.

Chavez said that researchers still have much work to do to understand the complexities behind this biological process, but unknowns encourage the team to keep working. New questions push Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute scientists to comprehend yet another part of the ocean’s biological pump and the little plant flecks riding the currents.

Image: A crew deploys an Environmental Sample Processor as part of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute CANON project (Credit: Alba Marina Cobo Viveros)

0 comments