Ocean Nitrogen Fixation In South Pacific Lower Than Predicted

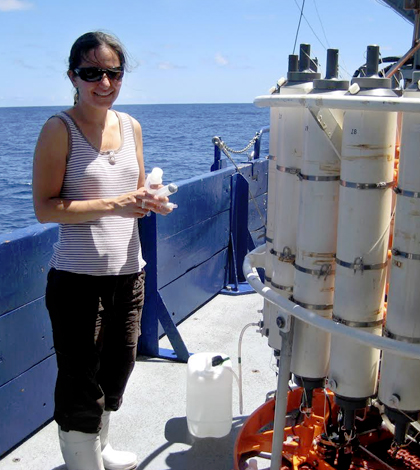

Angela Knapp stands next to a niskin rosette that was used to take water samples at various depths in the eastern South Pacific Ocean. (Credit: Florida State University)

Back in 2007, University of Washington-led modelers predicted that a region of the South Pacific Ocean had the highest rates of nitrogen fixation around the world. There was some agreement from experts in remote sensing at Oregon State University and University of California, Santa Barbara, who had predicted similar rates just a year before. But many biologists were left scratching their heads because there just wasn’t that much iron deposition in the area, an important supporter of nitrogen-fixing microbes.

The confusion needed to be resolved for a few reasons. One was that knowing about nitrogen fixation in the region would help to make ocean models more accurate. But more advanced understanding of the process would also reveal insights into the needs and functions of organisms responsible for making it happen, the nitrogen fixers.

Angela Knapp, an assistant professor of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science at Florida State University, has recently led an investigation looking to reduce the uncertainty brought about by the two studies. But because she works with both groups and respects their judgment, she had to approach the work with some impartiality.

“I was torn because I’m close colleagues with both the modelers and the remote sensing group,” said Knapp. “I guess I thought we’d find higher rates than we actually found.”

To see which prediction won out, Knapp and a crew of researchers journeyed to an area in international waters off the coast of South America. It was far from the coast in the heart of the South Pacific. Getting there, over the course of a few years, required obtaining passage on Research Vessels Atlantis and Melville.

The idea behind the expedition was to directly test the predictions that had been made concerning nitrogen fixation in the South Pacific.

“We used all the tools you could possibly use to measure carbon and nitrogen fixation,” said Knapp. Biologists onboard were using molecular tools to look at DNA and RNA abundance of nitrogen-fixing organisms. Geochemists, meanwhile, were relying on measurements of nitrogen concentrations and isotopic compositions.

But considering those things required lots and lots of water samples, which were gathered by a rosette of 12-liter Niskin bottles. This was lowered down to depths of 5,000 meters while pre-programmed triggers sealed off bottles as they reached various points.

“We collected at several depths — 0, 20, 50, 75, 100 — all the way down to 5,000 meters,” said Knapp. “It takes a long time to go that far. Many hours.”

Some nutrient-concentration measurements were made at sea because they were easier to do there, she says. But then all the of the samples collected were frozen and taken back to the lab for analysis.

“They’re (samples) pretty constant. They don’t change much,” said Knapp. “Keeping them frozen is a viable method for preserving them.”

All of the data revealed some surprising rates of nitrogen fixation going on in the region, ones that went directly against previous predictions.

“We found very low rates of nitrogen fixation in this region of the ocean,” said Knapp. “This is important for a couple reasons. The first is that it’s inconsistent from the modeling and remote-sensing work.”

But another reason is that it tells us about the sensitivities of organisms that carry out nitrogen fixation in the area, Knapp says. There are microbes there that scientists know have high requirements for iron. It seems likely that there just isn’t enough iron being deposited there in the form of dust from deserts.

“There’s not a lot coming off the Atacama (Desert in Chile),” said Knapp. “The fact that we see low fixation is consistent with the fact that we see low rates of dust.”

The findings essentially confirm biologists’ predictions that nitrogen fixation rates would be low there. But why do they contrast with those from the two older investigations so greatly? It appears that the models discounted the importance of iron for nitrogen fixers.

“One of the important findings was that there’s really no nitrogen fixation here. We don’t understand the distribution of nitrogen fixation in the ocean and how it’s controlled by biology. These microbes are sensitive to oxygen, iron and phosphorus concentrations,” said Knapp. “Our work supports the hypothesis that the low rates of nitrogen fixation are due to low iron concentrations, but does not prove the hypothesis.”

Top image: Angela Knapp stands next to a Niskin rosette that was used to take water samples at various depths in the eastern South Pacific Ocean. (Credit: Angela Knapp / Florida State University)

0 comments