Oil-flushing Mississippi River pulse also boosted coastal wetland production

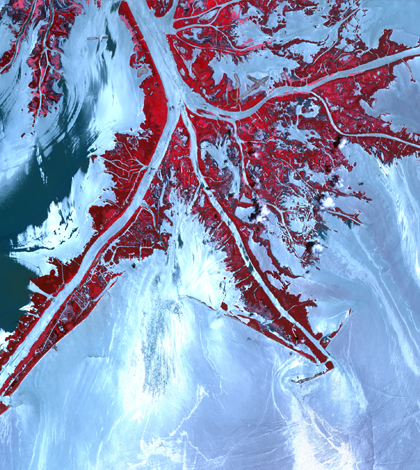

Oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill approaches the tip of the Mississippi River Delta in this May 24, 2010 satellite image. (Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

The baldcypress trees in one patch of Louisiana wetlands thrived following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, according to a new study. A strategy to release extra water from the Mississippi River to push oil away from the coast mimicked a tactic that conservationists hope could slow the loss of coastal wetlands.

Rising sea levels and subsiding land are sinking coastal wetlands while dams along the Mississippi have cut off the supply of silt that could build the land back up. Louisiana’s state plan for coastal restoration and hurricane protection recommends increasing freshwater flows through diversion structures to deliver silt and water to nourish wetlands. That was more or less what happened when the all state’s diversions were opened to full or near full capacity after the spill to flush oil away from coastal wetlands.

Beth Middleton, a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Louisiana-based National Wetlands Research Center, for two growing seasons measured the effects on trees from the extra water moving through the Davis Pond Diversion and into long-term wetland study sites within the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve.

“It was a rare opportunity,” she said. “Something that isn’t going to happen very often — an accidental experiment.”

Middleton and her colleagues set leaf litter traps to measure tree productivity. (Credit: Beth Middleton/U.S. Geological Survey)

The results of the study, co-authored by Brian Roberts and Darren Johnson and accepted for publication in Ecohydrology, were surprising, she said. For four months after the spill began in April 2010, six-times more water flowed through the Davis Pond Diversion than usual. After that, the canopies in the study sites produced 2.7-times more leaf litter than usual. Root production dropped off at first, but rebounded in the second growing season after the pulse. Leaf production remained high the second year.

That production boost is important because the extra organic material could help the baldcypress forests keep up with the rate of sinking. There are a number of factors contributing to that rate, including oil and gas development, shifting faults and a lack of new sediment flowing in from the Mississippi. But if plants are growing healthily, they can often stay ahead of sinking land and rising seas and shore up the land with organic matter.

Justin Stelly with a pore water sipper for taking salinity measurements. (Credit: Beth Middleton/U.S. Geological Survey)

This study, funded by a National Science Foundation rapid response grant, isn’t the first research to show freshwater pulses can boost plant production in wetlands near the coasts. An Australian study found that, for two growing seasons after two months of freshwater releases in the Murray River drainage, healthy eucalyptus trees “vigorously grew more foliage,” Middleton and her colleagues wrote in their report. Another study in other Louisiana wetlands found that baldcypress trees grew twice as fast with occasional pulses of river water than without. The freshwater inputs appear to help by flushing out water that has grown too anoxic or saline for wetland species to grow well.

Though some water managers would like to see more freshwater diversions near the Louisiana coast to boost wetland production, not all of them feel that way, Middleton said. Water management is controversial in the state, and there are other interests to consider beyond wetland trees. For example, the pulse studied by Middleton has been implicated in the declining oyster harvests that have occurred since the oil spill.

Though diversions may not be the perfect solution, the study shows how management might use them to foster wetland tree growth, especially in times of drought or as the effects of climate change become more dramatic.

“A study like this can’t speak to the whole,” she said. “It can speak to how the trees perform, though.”

Top image: Oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill approaches the tip of the Mississippi River Delta in this May 24, 2010 satellite image. (Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

guodong wang

May 10, 2015 at 10:20 pm

very cool! I am proud that I joined this study as a volunteer.