Researchers pitch ocean floor tents to examine coral’s role in an acidifying ocean

A team of researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography examined small patches of coral reef with ocean floor tents to understand how the organisms regulate an increasingly acidic ocean.

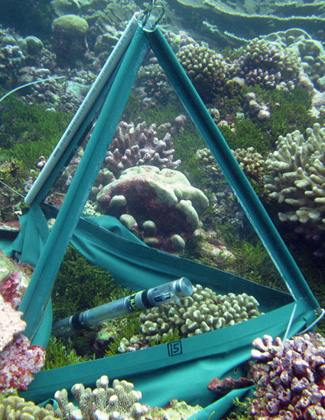

The researchers honed in on several small patches of reef using 24-hour, small-scale observations. Each run, they isolate six areas the size of a school desk with small tents, which seal in a small volume of water. Then they monitor the water to observe how coral reefs interact with the surrounding waters.

“We swim down and it’s just like pitching a tent when you go camping,” said Nichole Price, a Scripps post-doctoral researcher.

It’s like camping, except the site is a vibrant coral reef, sharks coast around investigating who’s in their territory and the scientists are in full scuba gear.

The Scripps researchers conducted the study on the remote northern Line Islands in the Central Pacific. There, coral reefs shelter and build the coastlines surrounding a string of small, low-lying atolls situated just above the equator. Three islands visited during the expedition are inhabited and part of the Republic of Kiribati; another three islands are unpeopled and are protected under the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

The team started traveling to these reefs in 2005. Their goal was to find pristine, untouched reefs to study. “These Islands provide an excellent juxtaposition of different levels of human impact for a research purpose,” Price said.

The researchers monitored seawater pH, dissolved oxygen, salinity and temperature for a 24 hour period with Eureka sondes (Credit: Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

They surveyed the area and found pristine coral reefs near uninhabited islands and reefs affected by islands inhabited by the Kiribati people. The different areas acted as foil models for researchers to study.

The researchers monitored seawater pH, dissolved oxygen, salinity and temperature for a 24 hour period with Eureka sondes, Price said.

A circulation pump keeps water moving in the tents and extracted water samples. They sample once they pitch the tent and again 24 hours later.

Data collected shows a vivid picture of coral respiration and calcification. “(The reefs are) so built up with living structure that you can visualize the reef accreting, inhaling, and exhaling,” Price said.

She explained that coral reefs, like any other photosynthesizing organism, operate on a daily schedule. When it’s light, they photosynthesize, consuming carbon dioxide and raising ocean pH levels.

“At night the various breathing organisms are exhaling carbon dioxide and because it’s dark there’s no longer photosynthesis to consume it,” Price said.

Nightly carbon dioxide increases contribute to lower nightly ocean pH levels on all reefs. However, the researchers noticed that reefs near populated islands had more extreme pH lows at night.

The ocean works to maintain chemical equilibrium as pH fluctuates, but increased atmospheric carbon dioxide is moving the equilibrium point toward a more acidic ocean.

The oceans’ acidity increased by 30 percent since the industrial revolution, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Increased ocean acidity is bad news for coral: It can lead to a lower saturation of calcium carbonate, which coral use to build the reef. Price said that means trouble for the Kiribati inhabitants too, because they rely on the reefs to feed and protect them.

Ocean pH is not the only thing harming the coral. Pollution runoff and heavy fishing near inhabited Christmas, Fanning and Washington islands can foster harmful seaweed growth over coral reefs compared to pristine examples near uninhabited islands.

Despite somewhat bleak findings, Price said studying rare pristine reefs will help scientists find solutions to coral’s man-made ailments.

She said initiating sustainable land management practices would be a good start for the Kiribati people and the coral.

Price and some of her fellow researchers will be part of an American Museum and Natural History Center for Biodiversity and Conservation symposium on managing land resources to maintain island ecosystem health.

So far researchers have not been able to confirm whether or not their small scale observations can be expanded to a larger scale. The Scripps research team will travel to the southern Line Islands next fall to expand the study and continue learning about the Islands’ coral populations.

Top Image: Instruments within tent chambers help gauge the health of coral reefs (Credit: Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

0 comments