Study tracks nitrogen lost through insect emergence in Costa Rican streams

Mayfly on the River Kennet, Berkshire (Credit: David Hill, via Wikipedia Commons)

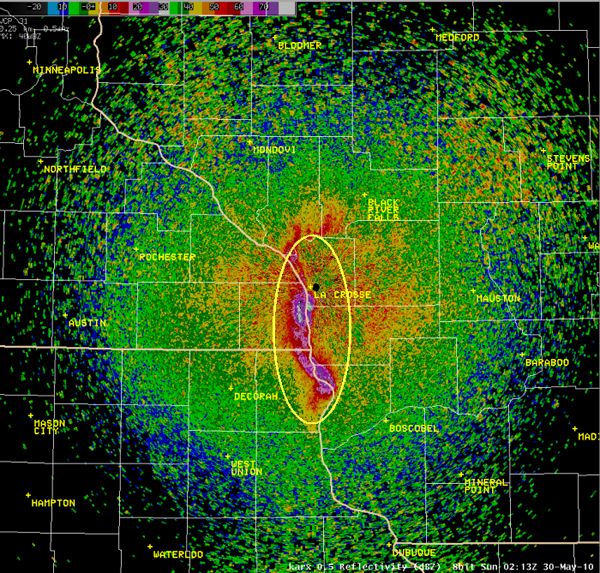

Some species of mayflies occasionally emerge from Midwestern rivers in such great numbers that the swarms show up on Doppler radar readings.

That gives an idea of the massive size of the emergences, but here’s another matter of scale to consider. Bound up in those buggy bodies is nitrogen that the insects took up as aquatic larvae — nitrogen that might have otherwise stayed in the stream, potentially sticking around long enough to flow out into a coastal ecosystem. Once there it would have contributed to a dead zone like the one in the Gulf of Mexico that grew to the size of Connecticut this year.

The excess nutrients that human activities like agriculture are sending into streams has researchers especially interested in the pathways through which nitrogen can naturally leave the water before causing problems downstream.

“In setting guidelines and trying to modify agricultural practices, it’s good to know how much of that nitrogen that enters the streams is actually going to make it all the way to coastal ecosystems where it’s going to have negative effects,” said Gaston Small, an assistant professor of biology at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn.

Nitrogen exits streams through insect emergences and microbial processes that transform nitrate into a gas that escapes into the atmosphere. But stream researchers tend to focus on one or the other. In a study led by Small recently published in the journal Freshwater Science, researchers measured both in streams flowing through the La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica.

A mayfly hatch along the Mississippi River mainly south of La Crosse, Wis. (Credit: National Weather Service, via Wikimedia Commons)

La Selva is an ideal place for nutrient cycling experiments because geothermal springs in the region send naturally high-phosphorous groundwater to some streams but not others.

“It’s kind of a natural laboratory for nutrient loading and nutrient pollution experiments,” Small said. “We’ve taken advantage of that system to ask some interesting questions about how phosphorous moves through the food web.”

Despite the convenience of highly varied phosphorous levels in nearby streams, the research was no tropical getaway. Though Small said he would occasionally stop and watch brightly colored macaws flying overhead, those sorts of moments were the exception.

“It’s pretty muggy and we’re up to our knees in mud and hiking miles through the forest carrying lots of heavy gear,” Small said. “It’s not glamorous.”

The gear included tent-like emergence traps that the researchers set up over several study streams, returning after a few nights with a modified Dust Buster to suck up the insects that were caught as they tried to leave the stream. By weighing the combined samples and assuming that about 10 percent (a proportion verified by past research) of bug biomass is nitrogen, the researchers could calculate the amount of the nutrient leaving the stream via insects each day.

Gaston Small alongside a stream in the La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica

The researchers also collected sediment samples to measure the denitrification rates at which benthic microbes in each study stream transform nitrate in the water column into nitrogen gas.

The researchers hypothesized that the streams with higher phosphorus levels would produce more insects and therefore have higher levels of nitrogen leaving the stream through insect emergences. That turned out not to be the case, as they detected no relationship between phosphorus levels and emergence rates.

“What that seemed to suggest was that in this extra insect production is really getting eaten by the fish,” Small said. “The bigger streams where there were more fish had lower emergence rates as well.”

What they were able to conclude was that insect emergence varied somewhat between streams, but not nearly as much as denitrification varied. Denitrification rates varied over orders of magnitude, whereas insect emergence varied over a three-fold range.

That means that the relative importance of insect emergence as a nitrogen flux is fairly significant in streams with low denitrification rates.

“Not that insects are going to change the nitrogen budget on a continental scale or fix the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico or anything like that,” Small said. “But if you’re talking insect emergence rates being 5 or 10 percent of denitrification … that’s significant. That’s worth looking at in these kinds of studies.”

Top image: Mayfly on the River Kennet, Berkshire (Credit: David Hill, via Wikipedia Commons)

0 comments