Water measurements buried in GPS signals earns international water prize for Colo. team

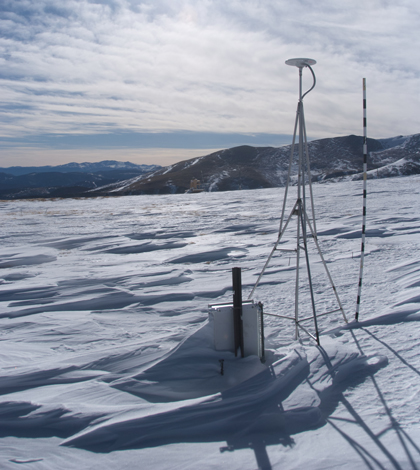

A GPS station at Niwot Ridge in the foothills above Boulder, Colorado, hosted initial snow-depth research. (Courtesy Ethan Gutmann/NCAR)

A group of researchers recently won an international water science award for making use of GPS signals that the team’s leader spent years trying to get rid of.

Kristine Larson, professor of aerospace engineering sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, originally trained to use GPS to measure motion along fault lines. But her career shifted toward figuring out what else besides positing could be mined from GPS data. The move paid off: The award-winning work produced techniques to process the noise in GPS signals into measurements of elements of the global water cycle.

“It’s pretty crazy that you could install an instrument to measure millimeter-per-year fault motions, and then simultaneously measure soil moisture, snow depth and vegetation,” Larson said.

Is especially surprising that the secret to measuring those water elements was buried in the background noise of GPS signals — the sort of noise that Larson had spent years trying to scrub away.

The signal that GPS satellites broadcast to Earth isn’t just a straight line directed at every antenna, but a wide signal that hits the antennas as well as a swath of the Earth’s surface. The antennas pick up the both the original signal as well as the reflections from nearby features.

“The reflected signal doesn’t tell you anything useful for positioning,” Larson said. “But it tells you something about what the signal reflected off of.”

Kristine Larson stands by the GPS station where their methods were first proven. (Photo by Glenn J. Asakawa/University of Colorado)

For example, a measure of the antenna’s apparent height can be derived from the pattern of interference between the direct and reflected signals. That distance will be different if, say, there’s a foot of snow sitting on the ground. The reflected signal will also vary depending on whether the surrounding soil is dry or wet, or vegetation is laden with moisture.

The techniques have since been validated and now serve as the basis for a monitoring network across the Western U.S. accessible through the PBO H2O Data Portal.

The “PBO” in that title is something of an indication of the wide potential for application of these methods. It stands for Plate Boundary Observatory, which is made up in part of 1,100 permanent GPS stations across the West that were installed to measure changes in the shape of the Earth’s surface resulting from shifting tectonic plates. They were notably not installed to measure water dynamics, yet today many of them they are.

“And if we can do it here, we can do it anywhere,” Larson said.

The idea of pulling novel measurements out of monitoring infrastructure that’s already in place goes against a tendency for scientists to want to design their own new networks and instruments that measure precisely what their interested in. That’s a fine approach if you live in a world of infinite resources, Larson said. But that’s not where she lives.

“I live in the world where you share data and you help each other and you try to measure as many things as you can with the existing instrumentation,” she said. “All we have to do is make connections with people all over the world that are already doing this.”

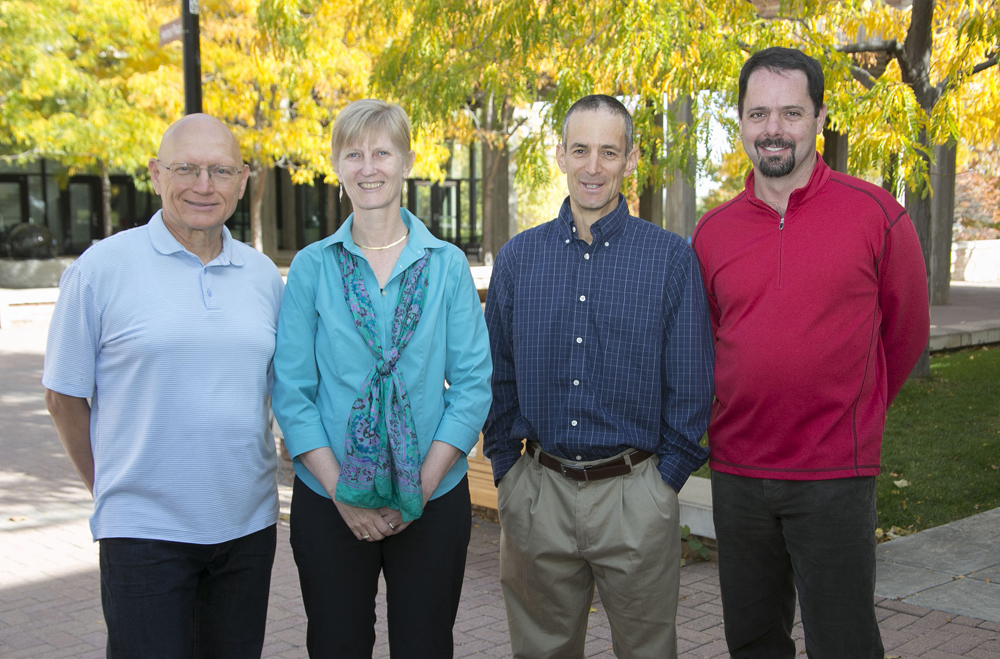

The research team of Valery Zavorotny of NOAA, Kristine Larson and Eric Small of University of Colorado Boulder, and John Braun of UCAR. (Credit: Bob Henson/UCAR)

Larson will accept the 2014 Creativity Prize from the Prince Sultan Bin Abdulaziz International Prize for Water on behalf of the research team, without whom the work would not have been possible, she said. The team includes Valery Zavorotny of NOAA, Eric Small of the University of Colorado Boulder and John Braun of the Boulder-based University Corporation for Atmospheric Research.

The prestigious award is a fine plot point in a story with modest beginnings.

“I started a decade ago, not funded, doing it on weekends and evenings,” Larson said. “Just looking at data.”

Top image: A GPS station at Niwot Ridge in the foothills above Boulder, Colorado, hosted initial snow-depth research. (Courtesy Ethan Gutmann/NCAR)

0 comments