Cornell-developed, fingernail-sized sensor measures moisture from within plants

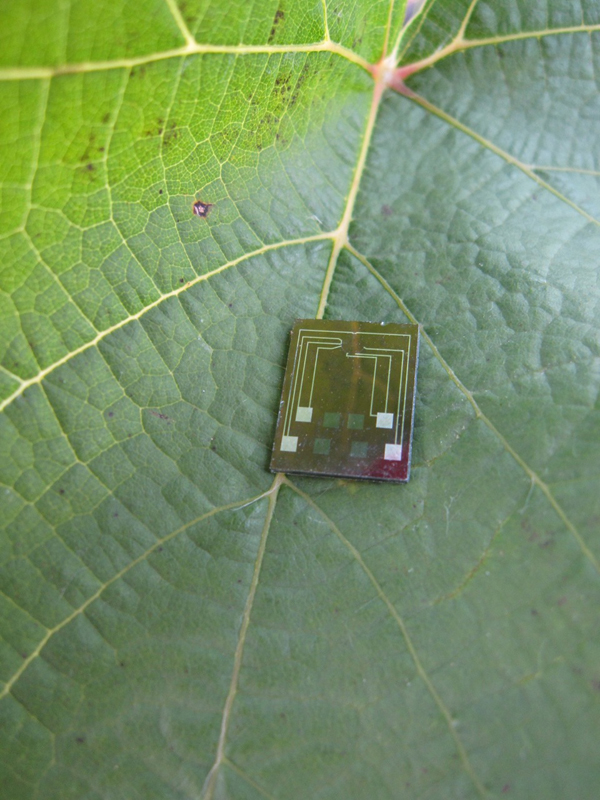

The new moisture sensor would be ideal for plants with dense, meandering root systems like grape vines. (Credit: Alan Lakso)

Soil probes are commonly used in agriculture to measure soil moisture. It’s an important parameter for an important job: growing food. But as it turns out, soil moisture sensors on the market today may not be ideal for all plants, especially ones with dense, meandering root systems like grape vines.

Using a standard soil probe, or a tensiometer – an old-school soil moisture measuring device – only gives a moisture reading for a small section of soil, about the size of a baseball. That’s a good sample, say researchers at Cornell University, but it’s far from comprehensive. The researchers say they’ve developed a better sensor, one that’s as small as a fingernail and easily implanted into growing vegetation.

“In soil, it’s a much more stable environment. We’re starting there first,” said Alan Lakso, professor of horticulture. “In the plant, inside a biological organism, will it try to exclude the chip or grow around it and integrate? No one’s ever done this before.”

Lakso says lab tests have shown that plants normally accept the implanted silicon sensor and grow with it in place. Putting one in the hard, woody part of a plant is easier than placing it in the fleshy green part. Whereas the wood portion will tend to grow in a predictable way, the green will grow, wind, shrink, swell and adapt to its environment as needed.

The sensor operates similarly inside plants as in soil, which is partly owed to its construction. Two thin sheets of silicon on one side bond with a layer of glass. In between the two halves is a small water-filled cavity encased by a porous material. This membrane is the key to the sensor’s accuracy and uses a microfluidic technique developed by Abraham Stroock, associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering. Because it is porous, the sensor’s membrane exchanges moisture with its surroundings to maintain pressure balance, which is converted into a moisture measurement.

“While a tensiometer will measure one bar of tension, these sensors will go zero to 100 bars. Some have measured 200 bars in tests,” said Lakso. In plants and soils, that’s an excessive range, but Lakso says it gives users a big safety factor. And the sensor’s small size makes it difficult for air to work its way into the membrane, maintaining good operation longer.

(Credit: Alan Lakso)

Theoretically, it is possible for the water to move in either direction and overload the sensor. But Lakso says the Cornell team, including doctoral student Vinay Pagay, is more concerned with what’s in the water outside the device. Anything from sugars, bacteria or salts could impact how the device functions, so they’re continuing tests to make sure those effects are minimized.

Collecting data from the sensors may take place in different ways, and Lakso says there is not a single best way of doing it.

“I visualize a push-pin, with the sensor in the pin part. Stick that in the tree,” said Lakso. “The knob could have a wire or wireless transmitter or solar cell on top. There’s quite a few ways of collecting the data.” Wires would connect to an external data logger or meter, says Lakso.

And since the sensors are so tiny, they don’t need much power. Lakso says they could be powered by wave action, though there isn’t yet a standardized method of doing that. If deployed in an industrial setting, vibrations from a factory could also be integrated into a power-supplying scheme.

Not much power is required for the sensors, and they shouldn’t cost much either. If a reliable mass-production method can be established, Lakso says the price for each might be around $5.

“Over an orchard or vineyard, one sensor gives you a very small sample. But if you could afford 10 to put in the same area,” said Lakso. “It’s much more inexpensive for researchers, hydrologists to take measurements, and lots of them.”

0 comments