Gordon the supercomputer models endangered species movements in 3-D

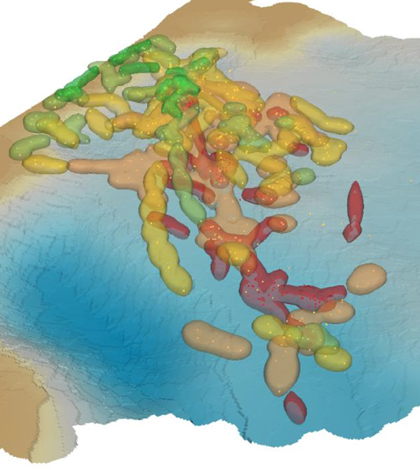

A 3-D probability map of where dugongs are likely to be at various tide levels (Credit: USGS)

Protecting threatened species is never an easy task, but those that cover large swaths of land, air or water in their lifetime can be especially troublesome. The U.S. Geological Survey and the San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research have developed new models to estimate the three-dimensional range and movements of threatened species using a supercomputer named Gordon.

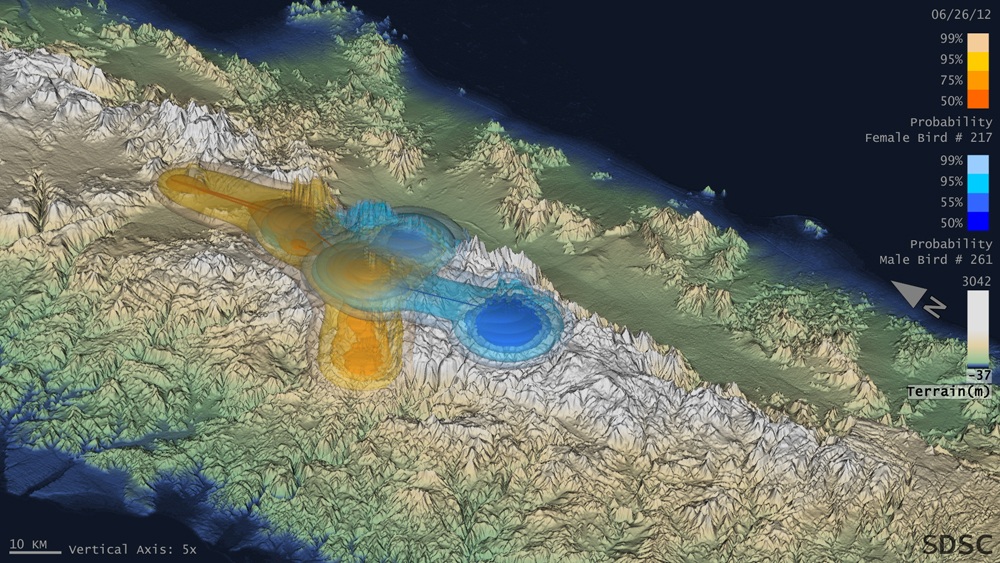

Focusing on the California condor, giant panda and dugong, the team worked with researchers at the San Diego Supercomputer Center and Gordon, one half of the Center’s supercomputing duo, to produce detailed 3-D visualizations showing an individual’s location across time and space. The three chosen species represent iconic threatened animals that have proven difficult to track due to their choice of habitat and movement behavior.

Jeff Tracey, a USGS computational ecologist and author of the study in which the models were developed, said that the project took off after his coauthor-to-be saw his presentation on animal movement behaviors.

“[James Sheppard] contacted me and basically explained that they had these condors that they bred in captivity and release in Baja, Mexico,” Tracey said. A researcher at the Institute for Conservation Research, Sheppard wanted to learn how condors used the landscape and what hazards they encountered there.

“We talked about different approaches we might take, and we decided to extend some of these movement-based 2-D models and extend them into the third dimension,” Tracey said.

The study’s authors used GPS transmitter data that other scientists had gathered from tagged animals. Sheppard gathered the condor and dugong data, while the Chinese Academy of Science in Beijing contributed the panda location data.

The study analyzed movement data from three endangered species: the California condor, the giant panda and the dugong (Credits in order: USFWS; John J. Mosesso/USGS; Julien Willem/CC BY-SA 3.0)

By moving from the second into the third dimension, the researchers were able to understand the behavior of their tracked subjects in new ways. Condors, for example, prefer to fly at certain altitudes. The researchers used the 3-D models to determine where wind turbines could be placed without affecting condor flight patterns.

The models provided insight into the other species’ movements as well. Pandas change elevation based on temperature and bamboo availability while roaming across wide stretches to find mates during the breeding season. And dugongs move between deep and shallow waters as the tide allows.

“One of the things that surprised me was that in the paper we described how the dugongs use space in three dimensions at different tidal levels,” Tracey said. “When the tide is high they tend to stay close to shore, and stay in deeper water at lower levels.” Understanding these movements, he said, could help the researchers learn when dugongs are most vulnerable to boating injuries.

The blue and orange surfaces, respectively, represent one pair of male and female birds analyzed in the study. ((Visualization credit: Amit Chourasia/Jeff Tracey/James Sheppard/ Glen Lockwood/Mahidhar Tatineni/Robert N. Fisher/Robert Sinkovits/San Diego Supercomputer Center/San Diego Zoo Global/USGS)

None of the modeling and visualization would have been viable without Gordon. Computations that took days on high-end PCs were accomplished in minutes with the supercomputer’s help. But that feat required plenty of code optimization by the folks at the SDSC, something that Tracey called “one of the main challenges” of the study.

Eventually, Tracey hopes that the research will expand to cover other raptor species in southern California, such as the golden eagle. As the methodology is refined over time, the modeling software will be released under an open-source license.

“Once we release this software, it’s going to be available for anyone to use,” Tracey said. “That’s ultimately the point: broader applicability for a variety of conservation uses.”

Top image: A 3-D probability map of where dugongs are likely to be at various tide levels (Credit: USGS)

0 comments