Modelers tap centuries-old charts, collect new data to predict future of U.S. estuaries

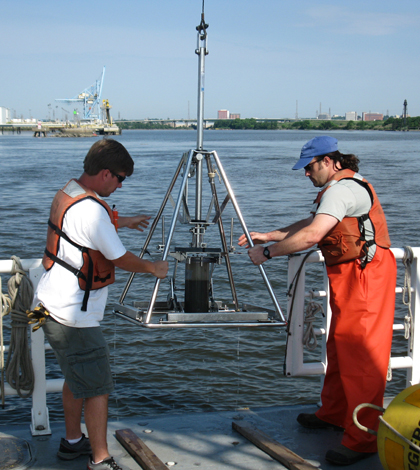

Technicians collecting riverbed sediment samples in the Delaware Estuary. (Credit: University of Delaware)

For oceanographers studying coastal estuaries, predicting the future means looking to the past.

Estuaries influence water quality, hold vital shipping canals and provide protection from coastal storms. With funding provided by the National Science Foundation-Science, Engineering and Education for Sustainability (SEES) program, a team of researchers is developing simulations to predict future human influences on several Eastern U.S. estuaries. The first step will be to digitize old hydrologic charts housed in archives at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The records go back about 150 years. Some go back to the 1800s.

“We’re digitizing old charts and bathymetry surveys into digital terrain models to see how similar those are to changes that have taken place,” said Chris Sommerfield, associate professor in the College of Earth, Ocean and Environment at University of Delaware. “I call it data rescue.”

Sommerfield, alongside researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Rutgers University and Drexel University, will be looking at the Delaware, Hudson and Raritan River estuaries along the Atlantic Coast. By looking at how those have changed in the past, the researchers will develop models to estimate future changes.

“The numerical modelers are going to start ramping up, doing hydrodynamic models on tides and weather,” said Sommerfield. “Once the models are calibrated for the present day, we’ll run mid-19th to mid-20th century simulations.”

The Hudson and Delaware Rivers will be studied for one to two years beginning in fall 2014. Sommerfield says there will be acoustic current meters at 12 different sites across the estuary, 30 meters apart to obtain data for model calibration. Study on the Raritan River will come later.

This satellite image captured in 2000 shows the New York–New Jersey Harbor Estuary–which receives water from the Hudson and Raritan Rivers–to the north and the Delaware Bay estuary to the south (Credit: NASA)

So what makes these rivers ideal for the study?

“These three estuaries are related in that they share the same watershed,” said Sommerfield. And since the United States was first settled in the area, there are more historical data from which to start.

After the river estuaries have been mapped, Sommerfield says the data set will be unprecedented in terms of study scope. The group is also charting nearby wetlands so that untouched estuaries can be compared to those impacted by human activity.

The advanced modeling is needed for growing populations that will increasingly rely on larger cargo vessels, and subsequently larger canals, as well as for predicting environmental costs associated with the expansions and their effects on water treatment systems.

“The models do a good job at capturing water flows and sediment transport from which to make predictions about changes in the bottom over time,” said Sommerfield. But the future models will be much more accurate and flexible. “So we can put a deeper harbor in, see what that will do to the estuary, to the wetlands. We could even throw in a Hurricane Sandy.”

Top image: Technicians collecting riverbed sediment samples in the Delaware Estuary. (Credit: University of Delaware)

0 comments