New sensor could shed light on understudied ultrafine particles

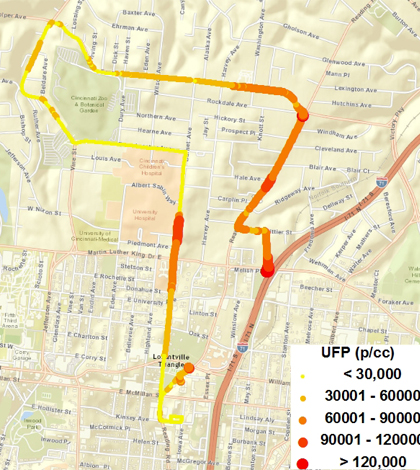

A map of ultrafine particle concentrations collected with the PUFP by Patrick Ryan around his neighborhood. (Credit: Patric Ryan)

Scientists studying the health effects of airborne particles around one thousandth the width of a human hair are closing in on their holy grail: wearable sensors that capture what individuals are truly exposed to.

The so-called ultrafine particles are less than 100 nanometers — much smaller particulate matter than the PM2.5 particles that are regulated, monitored across cities, and known to be associated with respiratory and cardiovascular health effects.

“The smaller these particles are, the deeper they can get into the airways, into the gas exchange regions,” said Patrick Ryan, an epidemiologist at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “These can actually go through the olfactory hub and directly into the brain and cause neural inflammation.”

The health effects of exposure to ultrafine particles haven’t been thoroughly studied because they’ve been difficult to measure, Ryan said. Their concentrations tend to be high near their sources — diesel traffic, for example — but as the particles collide and combine, they drop to background levels a few hundred meters away from their origin. While a dozen PM2.5 monitoring stations across a city might work for those larger particles, a similar network would miss the variability of ultra fine particles.

(Credit: Enmont, LLC)

While more stations and statistical modeling could help fill those gaps, Ryan says the “holy grail” of air pollution monitoring are personal sensors that track a person’s exposure as they move about their daily life. A new study led by Ryan suggests the field is getting closer to that. The researchers tested a recently developed ultrafine particle sensor on school children, asking 20 students to wear the device for 2 to 5 hours.

“We took it out of the laboratory for the first time and actually put it on some kids that had asthma,” said Ryan, who is also an associate professor of pediatrics and environmental health at the University of Cincinnati.

The Enmont personal ultrafine particle sensor, or PUFP, measures ultrafine particle concentrations once per second, along with GPS location that allows the data to be mapped. It could stand to be a little smaller and quieter, according to feedback from the participants. Though the device isn’t perfect, the results show that it can capture a variety of personal exposures while holding up against the rigors of being strapped to a kid’s backpack.

Prior to the PUFP, the standard devices for measuring ultrafine particles were the size of a shoebox or bigger and couldn’t be spun around or turned upside down. Sang Young Son, study co-author, assocaite professor of mechanical and materials engineering at the University of Cincinnati, and the engineer behind the PUFP, managed to shrink it down while measurement mechanism that isn’t as sensitive to jostling.

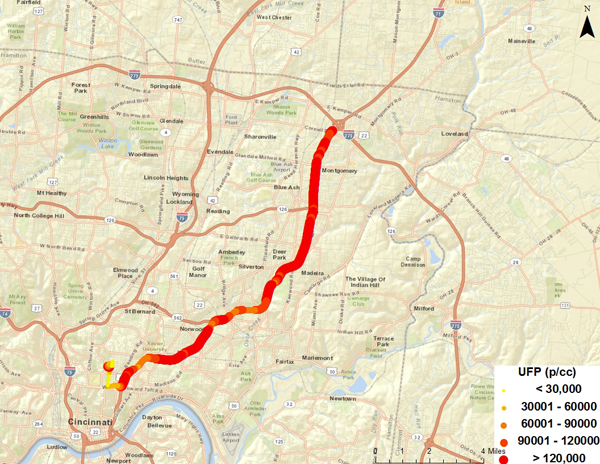

Ultrafine particle concentrations collected by Patrick Ryan with the PUFP during his daily commute. (Credit: Patrick Ryan)

The study was mostly a proof-of-concept that shows the device could be useful in a larger epidemiological study, but some of the data collected for the study is telling in its own right. The results, published in the journal Science of the Total Environment, showed no clear pattern in personal exposures, Ryan said. Some students saw their highest exposure at home, some while at school, and others while in transit between the two.

“The overall message is that those personal activities really do matter,” Ryan said. “Emphasizing the point that really need some way of capturing personal exposures if we’re going to try to look at health effects.”

The plan, depending on funding, is to further shrink the PUFP while dampening the noise from the motor that pumps in air. That could be followed by a larger study that asks around 100 students to wear the device for up to 8 hours a day for a week straight.

“The kids were willing to wear it for our study for two hours and a few days,” Ryan said. “We’ll find out in the future whether they’ll be willing to wear it for a week at a time.”

Top image: A map of ultrafine particle concentrations collected with the PUFP by Patrick Ryan around his neighborhood. (Credit: Patric Ryan)

0 comments