Novel seabed camera detects uptick in East Coast scallop numbers

A recent survey of juvenile scallops using an advanced underwater camera rig on the U.S. East Coast revealed that the population there experienced a substantial upshift.

The study by scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center found that juvenile scallops are particularly prolific in an area of Delaware Bay.

Preliminary numbers for the 2012 study show between 2.5 billion and five billion juvenile seed scallops in the Mid Atlantic study area. Scientists are waiting for the results of a second study next year to give final numbers, said Deborah Hart, mathematical biologist with the fisheries science center and leader of the sea scallop stock assessment.

Surveys in 2002 and 2003 found record numbers, turning up six billion to eight billion seed scallops. The 2012 count may be the second-highest ever if a follow up study confirms the numbers.

Similar numbers were seen by unaffiliated organizations in the fishing industry and the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences, according to a press release on the findings.

The Habitat Camera’s angular shape earned it the “Seahorse” nickname. (Credit: Shelley Dawicki/NEFSC/NOAA)

The special monitoring rig, called the “Seahorse” for its angular shape, was developed by scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Scientists tow the Seahorse at cruising speed of around seven knots. It glides two meters over the sea floor collecting data, according to a NESFC press release.

The rig carries a fluorometer, spectrometer, dissolved oxygen sensors and a conductivity, temperature and depth sensor. It also has a side-scan imaging system to plot benthic topography.

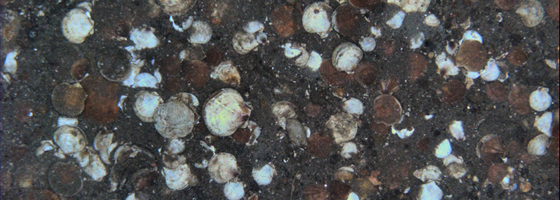

The Seahorse’s main tool is the latest version of the Habitat Camera Mapping System, or HabCam. The HabCam takes strings of pictures, which can be intertwined to give a mosaic of the ocean floor. The Seahorse allows scientists to observe bottom dwelling fish in their element.

Hart said the camera adds a new facet to scientific observation of scallops. “You’re not just catching what’s at the bottom,” she said. “You can actually see where the scallops are and see what other animals are doing there as well.”

For example, the camera showed scallops tend to stay together in the troughs of sand waves at Georges Bank. Sand dollars, on the other hand, aggregated on the crests of sand waves. That’s not something that a dredge tow would necessarily show.

The HabCam also shows tracks from fishing dredges, which can help researchers and regulators identify what is being fished in the area.

The HabCam took 7 million photographs during one 30-day leg of the journey. The researchers couldn’t sort through all 7 million images by hand. Instead, they went through every 200th picture, or about 35,000 total. That’s a picture approximately every 100 meters, Hart said. Other survey techniques have data points every four miles at best.

HabCam data showed that scallop population estimates from dredges were not far off. Hart said the validity of dredge counts has been a controversial topic, but the Seahorse only showed about a ten percent deviation in findings.

Scallops are the most valuable fishery on the East Coast. One reason scientists monitor them is to create sustainable fishing quotas. Once mature, the estimated seed scallops from the 2012 survey should bring in more than $500 million at the dock.

Hart said it’s hard to be certain why seed scallop populations ballooned this year, but she has a few ideas.

First, 2011 saw several strong rains from tropical storms and hurricanes. This flushed more nutrients into Delaware Bay, where seed scallops were most prolific. Nutrients fed plankton growth, which could have fed more young scallops and helped them flourish. Still, that’s a big “could,” and Hart certainly is not ready to point to the bloom as anything other than an unproven possibility.

A second possibility is that ocean currents may have carried young scallops into the study area from a nearby section of the ocean that is periodically closed to commercial fishing. Hart said when scallops spawn, they float up into the upper layers of the ocean, and the current could have sent them southward. She said she has twice seen populations spike after fishing closures. “Both times the biomass skyrocketed after the closure,” Hart said.

Despite these ideas, Hart said scallop populations spike and fall in unpredictable patterns.

Scallops on the ocean floor in the Great South Channel as seen by the HabCam on the Seahorse monitoring rig. (Credit: NEFSC/NOAA)

0 comments