Old Rocks In Kansas Help Geologists Solve Century-Old Question

The age of an outcrop of rocks near Elkhart, Kansas has baffled geologists for more than a century. (Credit: Kansas Geological Survey)

The study of rocks holds a lot of beauty in its own way. Slow and methodical, the hands-on work relies on well-known methods and standard tools like hammers. Perhaps that’s one reason geologists love what they do.

The time-tested approaches that the field has relied on over the years have yielded much in the way of new discoveries, including dating the Earth and the Moon. Except, that is, for the age of a small outcrop of rocks in Kansas that they’d missed.

The rocks, a stark red in the midst of green shrubbery and grassland near Elkhart, are mostly red shale and sandstone. For more than a century, the age of the rocky layers have baffled geologists across the state of Kansas. But new finds from the Kansas Geological Survey have finally determined just how old they are, using some of the same old-fashioned methods — with a twist.

“It’s funny about how this came about. But if you read in the literature, it seems like a lot of people didn’t go out and actually see them (the rocks) themselves,” said Jon Smith, a research scientist at the Kansas Geological Survey. “It took me about seven hours to drive there. But in the old days, in the 1920s, it was harder to cover more territories.”

So that was one reason that the age of the rocks was disputed for so long, dating back 115 years. Another is that rocks from different ages — 300 million years’ old versus 50 million years’ old, for example — can look quite similar. Outcrops of rocks in the surrounding area dated to different time periods had also misled a few researchers throughout history, including during times where there was a reliance on fossil finds to date rocks much more so than there is today.

It was the mission of Smith and others to find a more reliable and foolproof method for dating the rocks — one that would finally put the guessing game about their age to bed.

“We tried to cut through all of that. We were going to cut through all of that by using a special technique,” said Smith. “That’s where the zircons came in.”

Zircon crystals have been used for some time in geological research. Though large ones are rare, smaller ones embedded in the grains of sedimentary rocks aren’t hard to come by. What’s more, they give researchers a perfect time tracker: The crystals contain uranium when they form.

Now it’s not really the uranium that does the trick for geologists — it’s the rate at which it decays, typically over the course of millions, or billions, of years.

To analyze the zircon crystals in the rocky outcrop, geologists with the state’s survey used some of those same old methods to grab samples. “We basically used a rock hammer, Jacob’s staff and a sight level to measure the site’s rock beds,” said Smith. For clarity, a Jacob’s staff is a widely used geological instrument that is placed on the ground near sites being surveyed to support compasses or other instruments.

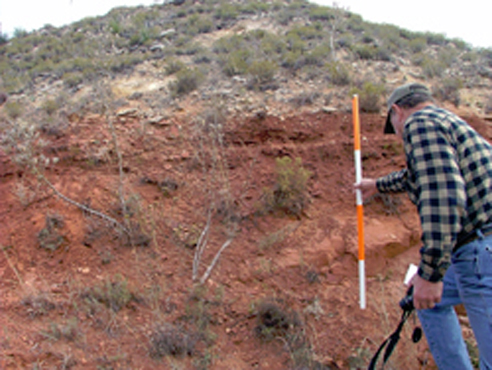

A geologist samples one of the red rock outcrops in Southwest Kansas. (Credit: Kansas Geological Survey)

The samples gathered, four in total, were then sent to a Kansas Geological Survey lab as well as another on the campus of the University of Kansas. Within these, the samples underwent a complex procedure to assess the zircons they held. One sample was unsuccessfully dissected, but the other three came through.

After being crushed, scientists worked to sift out the zircons in each sample using liquid separation techniques, relying on zircon’s greater density, when compared to other minerals, to sink to the bottom of test tubes.

“The takeaway point is that the liquids we used are very high-density. So most silicate minerals will float but the zircons are so dense that they’ll sink,” said Smith. “The zircons are taken and individually zapped with a laser and we’re looking for the ratio of lead vaporized to uranium because uranium decays to lead over time. We know that curve and we’re able to identify individual zircons and their age.”

From just one sample of sedimentary rock, Smith says, you’ll get a spectrum of uranium-lead ages. A bunch will hit a certain age, while others will range. The ones that are the youngest show a limit to the age that the deposits can be.

For the rocks near Elkhart, the zircon analysis decimated an old theory that they hailed from the Jurassic Period and determined a much older age: The rocks were formed in the Permian Period, when all of the Earth’s major landmasses were gathered into the supercontinent Pangaea.

“I wasn’t surprised one way or the other because no one had really taken a close look at it,” said Smith. “A couple folks here at the Survey had thought about it for a while. And it just stuck in somebody’s craw that we didn’t have a good line of evidence to propose an age for these rocks.”

But there are still many implications for the results, beyond just dating the rocks. Smith says that knowing their age will help inform future understanding of what the Permian Period was really like, including variables like the locations of coasts or high and low points making up geography then. Those dynamics are often the foundation of exploration for oil or gas by the energy industry in the present day.

As for climate change effects, knowing more about these rocks tells scientists more about periods of Earth’s past that had similar climates to the one we live within today.

“By reconstructing pictures of the past, we can make predictions about the future,” said Smith. “If current conditions change to match, maybe these are some of the things we’re going to see. It’s a way to predict the future more than anything.”

Top image: The age of an outcrop of rocks near Elkhart, Kansas has baffled geologists for more than a century. (Credit: Kansas Geological Survey)

0 comments