From submerged logging to mapping habitat, sonar can help

Access to sonar system technology for mapping underwater surfaces was once limited by five-figure price tags. But now side-scan sonar is more affordable and its applications are broad, from ecologists mapping aquatic habitat to underwater loggers pulling valuable 200-year-old sunken timber from riverbeds.

The Cape Fear River, which flows through North Carolina and into the Atlantic Ocean at Wilmington, once carried longleaf pine logs cut from the region’s old-growth forests to downstream sawmills. Modern pine lumber might have 2 to 3 growth rings per inch, according to John Payne, co-owner, along with Bill Moore, of Cape Fear Riverwood. Old-growth longleaf logs, already hundreds of years old when they were cut as far back as the 1700s, have 20 to 30.

“They’re extremely dense,” Payne said. “And they’re so dense, of course, they don’t float.”

As a result, the bed of the Cape Fear River is littered with old logs that escaped the rafts on their way to the mill. And as a source of high-quality wood that could otherwise only come from cutting old-growth forests, the logs are too valuable to leave down there.

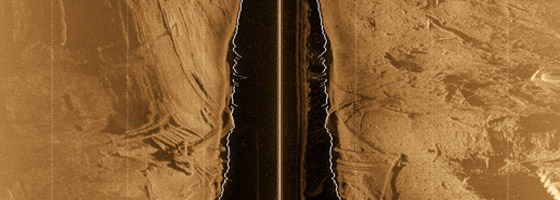

That’s where Cape Fear Riverwood and underwater imaging technology comes in. After scouting the depth of a section of the river where Payne and his crew are legally permitted to pull logs, they’ll come back with a 17-foot johnboat towing a Starfish brand side-scan sonar system. The instrument plugs into a onboard PC that displays an image of the riverbed and GPS coordinates.

“When you put this thing in the water, you immediately see logs.” Payne said. “This river is full of logs.”

When the crew spots promising logs, they plot the coordinates on Google Earth. Back on land, they’ll review their map and notes and plan a return trip with a barge-mounted boom and retrieve 300 to 350 logs over a few days. That provides enough lumber to produce floorboards, paneling and mantle pieces for a few months.

Payne said Cape Fear Riverwood’s customers appreciate the historical value of wood that was originally claimed by and cut for King George III, the monarch who lead Great Britain during the Revolutionary War. The company appreciates the history, too. Payne recognizes that the company’s use of these logs, which North Carolina considers state artifacts and requires a permit to retrieve, is a privilege. He’s happy to work with the state’s archaeological community whenever they come across anything that could be historically significant.

“If we pull up logs and there is some other kind of artifact there—a boat part, whatever it is—we immediately stop, we call the archaeological people, and they come out and they do their own investigation,” Payne said. “We’re providing that service to them in return for them allowing us to use these state artifacts. So it’s a great deal.”

Habitat mapping breakthrough

Submerged logging in the Southeastern U.S. also led Adam Kaeser to side-scan sonar, though his goals were much different.

In 2006, Kaeser was working for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, which wanted to gather information on the distribution and ecological role of sunken pre-cut logs. While surveying rivers for logs with a sonar system manufactured by Humminbird, Kaeser saw how clearly it displayed important habitat features of the riverbed like sand, gravel and woody debris. That led Kaeser and DNR GIS specialist Thomas Litts to pioneer a method for developing large-scale underwater habitat maps—a tool once largely limited to land-based wildlife researchers and managers.

The method involves floating a section of stream with a boat-mounted sonar, manually capturing overlapping screenshots of the river bottom from the sonar display. Using tools developed by Litts, the images are processed and brought into a GIS program and reassembled to fit the bends and course of the stream. From there, various habitat features are manually interpreted and labelled.

So far, Kaeser and Litts have produced complete habitat maps for 15-mile-long streams—a revelation for river and stream ecologist who are often limited to working on a smaller scales of a hundred yards to a mile.

“It just opens up a lot of doors for analyses of habitat use at the landscape scale,” Kaeser said. “That type of thing has been difficult to do for fish or other organisms in large non-wadeable riverine systems simply because it’s difficult to map those areas completely.”

Now a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Kaeser has used these habitat maps to study turtle habitat as well as competition and habitat overlap between three species of black basses. He and Litts have published several articles on the method in journals including Fisheries and River Research and Applications, and have taught workshops at venues including meetings of the American Fisheries Society.

“I’m constantly getting phone calls and emails with all kinds of questions from people who are either picking up this technique or are in the middle of projects right now,” Kaeser said. “As far as I can tell, it’s definitely gaining momentum.”

Top image: An image produced by a Starfish side-scan sonar system reveals sunken logs in the Cape Fear River (Credit: John Payne)

0 comments