No Evidence of Natural Gas From Fracking In Ohio Drinking Water

UC geology professor Amy Townsend-Small uses gas chromatography to study water samples taken from groundwater wells in Ohio. (Credit: Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services, https://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/pub/170963.php)

A recent study of Appalachian Ohio drinking water from private wells found no evidence of natural gas contamination from “fracking” (drilling for oil and gas) despite concerns about the practice. University of Cincinnati geologists investigated drinking water in Carroll, Harrison, and Stark counties, a rural area in the northeast portion of the state, where private underground wells are the only source of drinking water for many residents.

Associate professor of geology Amy Townsend-Small described the time-series study, which is the first to measure sources and concentrations of methane in the fracking region of Ohio, to EM.

“Most of the groundwater wells in our study had methane with an isotopic signature that indicated it had a biological source, so not from natural gas,” explains Dr. Townsend-Small. “Methane itself, from any source, isn’t toxic, but it can present an explosion hazard at high concentrations. A few of our groundwater wells did have biological methane at the levels that could present an explosion hazard. If natural gas methane had been detected, that could have indicated the presence of other hydrocarbons that are present in natural gas that are toxic like benzene, but we didn’t measure that in our sites.”

In fact, there are multiple potential sources of methane in these kinds of wells.

A typical shale gas well in Ohio next to a farm. (Credit: Dr. Townsend-Small, via communication)

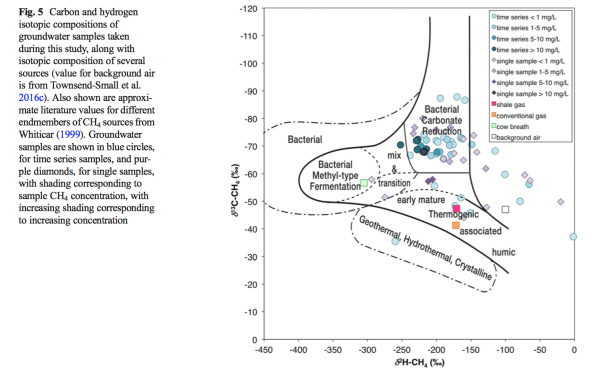

“We measured carbon and hydrogen stable isotopic composition of methane, and that dual isotope approach can distinguish between many different sources of methane,” details Dr. Townsend-Small. “You can see the different sources in Figure 5 of our paper.”

Originally, the team selected counties and individual wells for monitoring based on demand for permits.

“We started the monitoring in Carroll County in 2012, which was the location of the most permits for fracking wells at that time,” Dr. Townsend-Small recalls. “Later in the study, we added groundwater wells in the surrounding counties which were expected to have fracking activity so that there would be a baseline. The groundwater wells were all selected based on homeowner interest and on a voluntary basis.”

The team of UC researchers collected a total of 180 groundwater samples in homes within the three counties under investigation. They sampled multiple times at some of the sites. Over the four years they studied the area, they found no change in methane composition or increased concentration in the groundwater—even though new drilling sites opened in the study area. Additionally, methane levels did not rise with close proximity to drilling sites.

“We used an isotope ratio mass spectrometer for measuring the stable isotopes of methane, and we also measured the radiocarbon age of methane in some of the samples using accelerator mass spectrometry,” adds Dr. Townsend-Small.

Figure 5: Isotopic compositions of groundwater samples. (Credit: Botner et al., https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10661-018-6696-1.)

Obviously the team tested for evidence of methane, but they also looked for changes in the acidity or pH of the water, and changes to its conductivity.

“We measured pH and conductivity because we thought they would be good indicators of the presence of fracking wastewater, which is known to be acidic and high in salts (high conductivity),” comments Dr. Townsend-Small.

Understanding the chemical composition of the methane itself helped the team to identify the sources.

“We actually analyzed the chemical composition of methane—the number of neutrons in each atom in the methane molecule,” remarks Dr. Townsend-Small. “The ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12 and hydrogen-2 to hydrogen-1 in methane in the groundwater identifies the methane production pathway—which can be from different biological pathways or from the chemical and physical process that converts plant material to natural gas.”

The correlation between gas drilling and methane in wells has been observed elsewhere—in Pennsylvania, for example. However, the connection was not observed in this research.

“The researchers who found the natural gas in the groundwater wells in Pennsylvania think it was caused by failed gas well casings, and hopefully that won’t happen anytime soon in our study area in Ohio,” adds Dr. Townsend-Small.

The team did detect a wide range of methane concentrations in local drinking water. In fact, methane concentrations varied from 0.2 micrograms per liter to a flammable 25.3 milligrams per liter. The team found no relationship between these observed methane levels and the drilling sites.

However, as drilling increases in the area, further monitoring will be important. Moreover, it will be important to expand this study to seek out carbonate isotopes associated with drilling for natural gas, and to include other hydrocarbons such as propane.

Author Claire Botner (left) with students Frida Akerstrom (right) and Caset White (middle). (Credit: Dr. Townsend-Small, via communication)

“We only used one indicator of methane source—isotopes of methane—in our groundwater study,” comments Dr. Townsend-Small. “The other indicators would help confirm the source, which would be really helpful, especially in the case of contamination of natural gas.”

Of course, for the people in this area, this kind of testing is critically important since they rely on their wells entirely.

“People with private groundwater wells are responsible for their own water testing,” remarks Dr. Townsend-Small. “We provided free water testing for methane concentration, isotopic composition, and pH and conductivity during the study period, but we don’t have any more funding, so people are on their own now. They can send water samples to a private lab and pay to have them analyzed.”

The study area is situated directly above the Utica Shale formation, a geological feature rich with oil and natural gas. Between 2012 and 2015, the years of the study, drilling permits in the region went from 115 to almost 1,600, signaling a need for ongoing monitoring of the issue. Despite the current good news for residents, private well contamination is always a looming threat—one that careful monitoring can help defang.

Top image: UC geology professor Amy Townsend-Small uses gas chromatography to study water samples taken from groundwater wells in Ohio. (Credit: Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services, https://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/pub/170963.php)

0 comments