Water in the Desert: The USGS and Arizona’s Water Challenges

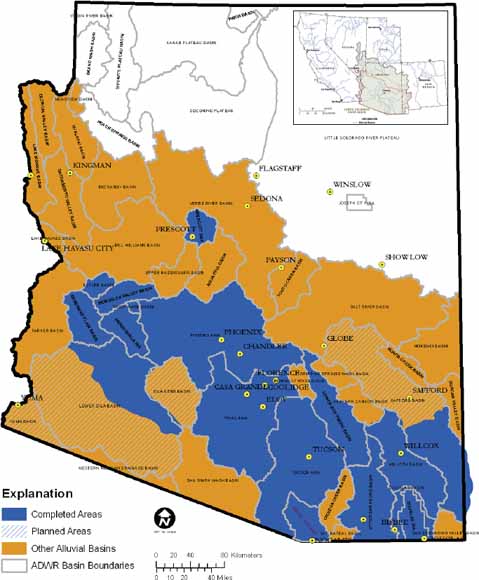

Groundwater conditions in Arizona. (Credit: USGS.)

In a state that knows water is perhaps the single most decisive factor in its continued existence, the Arizona Water Center (AWC), part of the United States Geological Survey (USGS), plays a critically important role. James Leenhouts, Director of the AWC and a hydrologist by training, has lived in Arizona for decades, and devoted his career to helping Arizonans cope with the unique challenges water presents.

“A key part of what we do is provide information for resource managers to answer their questions,” Leenhouts explains. “For example, if someone wants to put wells in a certain place in the aquifer, how will it affect nearby wells?”

It’s a fair question. Key to the mission of the AWC is the production of unbiased hydrologic data and studies that can readily be applied to a broad range of water-resource management issues throughout the state. About 80 percent of the state’s water goes toward agricultural uses, with the remaining reserves meeting domestic demands. Add to the mix the water needs of the 21 Native American tribes of Arizona—19 of which are recognized by the federal government—and their reservation lands which comprise more than 25 percent of the State. Along with explosive growth in urban populations and related demands on local water, and you’ve got the complex tangle of water rights stakeholders in the state.

“We’ve got a really rich database of water use from across the state,” Leenhouts offers. “In fact, although you might not expect it, water use has gone down since 1980 despite population growth, and this is all management related.”

Gages and groundwater

In a state like Arizona, these kinds of management questions have always been important. In fact, the center has data going back to gage observations taken in 1903, nine years before Arizona was a state. Today there are 225 gages in select streams throughout the state, a network used to monitor streamflow conditions. These gages help the AWC team advise stakeholders in a variety of matters, including bridge design, flood-plain zoning, flood warning and frequency, recreation, reservoir operations, water rights, water supply, and many other water uses. Each is checked every four to six weeks.

A rider fills his keg from a desert well in the territory of Arizona in 1907. (Credit: By Unknown or not provided (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

In Arizona, the skill and experience to understand the data are almost as important as the data itself.

“So much of what happens with water depends on what happens with precipitation, what happens with temperatures,” Leenhouts clarifies. “We have to interpret the data, and figure out why things do what they do, and what are the processes that cause contamination in one area and not another.”

The task of the AWC is also unique due to the difference in the way groundwater in Arizona is recharged.

“The southwest is unusual in its climate and how we get precipitation and streamflow. Most of our streams are dry most of the year, and this has several implications,” Leenhouts explains. “If there are surface contaminants building up, rain causes them to move off all at once. Groundwater in humid areas it recharges all year long, but not here. We can have little to no recharge for years, and then a wet season recharges things in a massive way, 5 to 10 years at once that affects groundwater, how streams respond, and connections between streams and aquifers.”

The AWC team can study these forces in action in specific locations to find out how aquifers and streams that enjoy substantial recharging only once in awhile are affected by things like human interventions and weather events. For example, the team can study and interpret the recharge rates and other issues as water is diverted from a stream or pumped from an aquifer, both immediately and over time.

Water gages in Arizona, December 3, 2017. (Credit: USGS.)

Answering management questions

Sometimes the AWC takes on projects guided by a particular problem or a specific management question. For example, the team has been collaborating with the National Park Service to determine how mass aerial spraying of Roundup, a broad-spectrum systemic herbicide and organophosphorus compound, impacts the groundwater and water quality. Specifically, the teams are assessing the impact of spraying on buffalo grass.

Another example Leenhouts describes is the Saguaro National Park project.

“Historical mines were abandoned there and became part of the park, so they inherited all of these problems,” Leenhouts states. “Open shafts, for example. Can they take waste rock from mines to close in shafts? If they did take that approach, would that cause groundwater contamination? What’s in the waste rock—lead, other contaminants maybe, or not. They need to know, because if they choose to dump the rock, there may be consequences.”

Fortunately, the AWC team is there to help policymakers and management make the best possible choices based on sound science.

Top image: Groundwater conditions in Arizona. (Credit: USGS.)

0 comments