Model of slow-moving river may make erosion predictions more precise

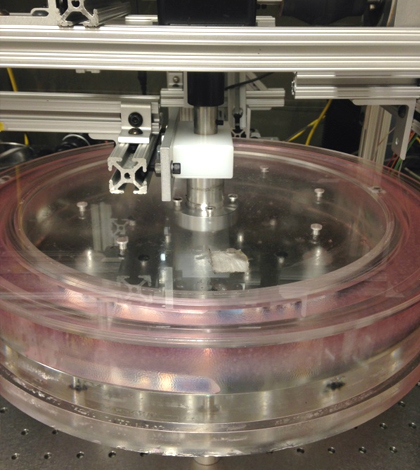

The simulated river, held in this donut-shaped container, has been dyed with a fluorescent dye to help scientists image the movement of small particles inside. (Credit: University of Pennsylvania)

Heavy flow conditions impact river sediment in sometimes dramatic ways, reshaping waterways and transporting large portions of dirt and silt downstream. But what about the slower flows, those that come through with much less notice and force? Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have found that these low flows are still mighty, impacting sediment both on and beneath rivers. As the low-speed flows come through, scientists found that river sediments creep forward, reshaping waterways in similar ways to faster flows. Their work, which relied on models of sediment transport built using custom equipment, may help make future erosion predictions more accurate.

“If we can understand when and how erosion occurs and show that our model is robust, some other smart person is going to take our result and develop a useful tool from that,” said Douglas Jerolmack, associate professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania, in a statement. “We’re producing a basic science result right now, but the applications are probably only as limited as our imaginations.”

Understanding how and when erosion occurs sheds new light on a question that has long puzzled geologists: Why do observations from nature rarely match patterns of sediment flows that they predict?

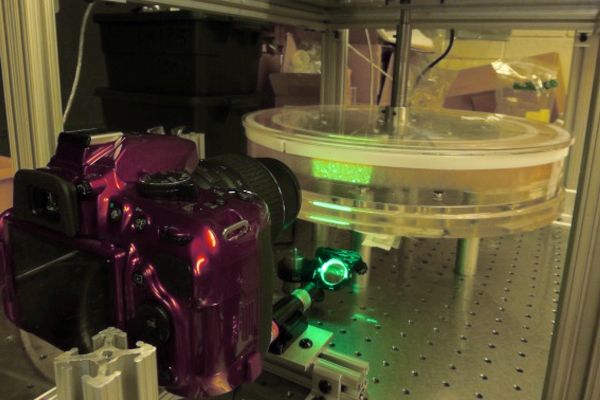

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania built this system in their lab to simulate the effects of water flow on river sediment. (Credit: University of Pennsylvania)

To get at the answer, scientists built their own miniature river. The device is shaped like a donut and is about the size of a fish tank. A spinning top helps churn the water around, while round particles on the bottom simulate river sediment. From there, researchers add fluorescent dye to the liquid and produce images of the simulated river bed with lasers.

The approach helped them track sediment motion all the way down to the movements of individual particles, but measuring a river’s creep, or the amount of overall erosion it contributes, is still difficult.

“We can’t say anything about the level of creep in rivers because no one has ever measured it,” Jerolmack said in a statement. “However, the slow creep of soil down a hillside due to gravity is well known, and a next step is to examine whether the underlying physics are the same.”

By taking slower, longer-term measurements in the field like the scientists have done in their lab, it may be possible for other geologists to better quantify sediment transport caused by river creeping. Such improved figures could make erosion estimates more accurate, as well as predictions of how landscapes nearby may change as a result.

“People often wonder how long they have to measure sediment transport in rivers to get a reliable result,” said Morgane Houssais, a postdoctoral researcher in earth and environmental science at Penn, in a statement. “We were able to infer the time you need to overcome the variability of the system and show that this time increases the slower your system moves.”

Top image: The simulated river, held in this donut-shaped container, has been dyed with a fluorescent dye to help scientists image the movement of small particles inside. (Credit: University of Pennsylvania)

0 comments