Newly restored wetlands are carbon sinks but may be net sources of methane

Long-lost wetlands converted to farmland can be turned into carbon sinks if they are restored to their former glory, scientists have found. But in a short window after restoration, the young wetlands may be net sources of methane emissions as they grow new aquatic plants.

Researchers at Dartmouth College, assisted by others at the University of California, made the discovery using eddy covariance towers deployed at four experimental sites in the San Joaquin River Delta, an area long-altered by drained wetlands used for farming.

“We chose this area because it used to be wetlands 150 years ago,” said Jaclyn Matthes, assistant professor of geography at Dartmouth. “We wanted to see if we could restore wetlands in an area after they’d been drained to see if we could turn them back into carbon sinks.”

Four sites were monitored using towers outfitted with Gill Windmaster Pro sonic anemometers; LI-COR 7500 carbon dioxide and water vapor sensors; and LI-COR 7700 methane sensors.

“One of the exciting developments for our work is the 7700 is the first low-powered sensor that can run off solar panels,” said Matthes. “That let us take measurements in the first place.” To power other methane sensors, she says, a generator or direct line power is often needed.

All the technology helped scientists measure the exchange, or flux, of greenhouse gases between the sites and their surrounding atmosphere. This was done by tracking the correlation between carbon dioxide and methane while considering vertical wind velocity.

Throughout the course of study, which began in 2010, Matthes and others made some useful findings. Farm fields were net sources for greenhouse gases. Fields that had been converted back to wetland were carbon sinks, but were emitting noticeable levels of methane.

“We saw the methane emissions increase over the first two years and then level off,” said Matthes. “And we’re continuing to measure this to see what they do in the future.”

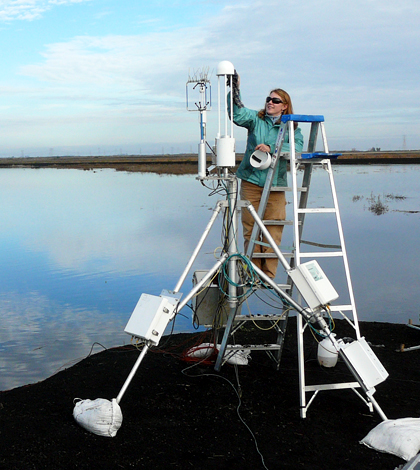

Researchers program an eddy flux tower at the wetland in summer 2012. (Credit: Jaclyn Matthes)

The finding is important for government agencies working to manage greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere because methane is 20 times better at trapping heat than carbon dioxide.

“Wetlands are carbon sinks, but there’s another way of evaluating,” said Matthes, especially considering that methane is more efficient at trapping heat. “If you evaluate it from that perspective, it looks like wetlands are greenhouse gas sources to the atmosphere.”

She and other researchers were surprised at how heavily methane weighed on the greenhouse gas balances of ecosystems they were studying. The investigation, she says, is one of the first to look at the methane levels consistently over time.

“It helps us by refining our definitions of methane emissions that wetlands make,” said Matthes.

Top image: Jaclyn Matthes cleaning the eddy flux tower shortly after it was installed at the newly flooded wetland in winter 2010. (Credit: Joe Verfaillie)

0 comments