Controlling Invasive Carp at a Blue-Ribbon Fishery

At Big Muddy National Fish & Wildlife Refuge in Missouri, an invasive Asian carp leaps high out of the water to escape biologists’ nets. (Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters [Public domain])

At Big Muddy National Fish & Wildlife Refuge in Missouri, an invasive Asian carp leaps high out of the water to escape biologists’ nets. (Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters [Public domain])Utah’s Pelican Lake is a hotspot for fishing among locals and tourists alike, but for the past several years it has fallen upon hard times thanks to an invasive species. Recently, officials have been working to alleviate the problem and restore a more balanced ecosystem to the lake. Utah Division of Wildlife Resources regional aquatics manager Trina Hedrick spoke to EM about the process.

“Pelican Lake is a nationally renowned, blue ribbon fishing hole, and has been since the 1970s,” explains Ms. Hedrick. “It’s had its ups and downs over the years, but within the last 10 years, quality of the fish has declined dramatically. There are two things going on, one of which is the carp.”

Carp have been in the lake for a while without causing problems, just in low numbers. Managers suspect that carp were flushed into the lake in high numbers in 2008 and 2009, which tipped the balance and caused this recent decline.

“At first there weren’t that many carp,” describes Ms. Hedrick. “The largemouth bass could just feed on their eggs and keep the carp population in check. But in 2008 and 2009, we had so many carp enter the system because they were doing a dam repair and had to drain a reservoir. It just flooded Pelican Lake with carp, and now, suddenly, these adult carp are producing way more eggs, so the population just grew.”

At the same time, the lake was experiencing increased sedimentation from the canal.

“It’s over 100 years old,” Ms. Hedrick details. “The water has eroded around drops in the canal, and we’ve seen a lot of sediment coming in and down, as water cuts in and through the canal. All that sediment coming in filled in the inlet and created a really shallow habitat that the carp loved.”

In other words, the erosive properties of water have given the carp approximately 40 extra acres to spawn every spring.

“So, we had these two things happening at the same time which just tipped the balance, and we started really following the bluegill population in about 2013, just to track it and see,” states Ms. Hedrick. “But we didn’t even need to do that; anglers could see the difference in growth rate and also just their condition. Bluegill were so skinny these last few years and we also observed declines in the condition of largemouth bass, which makes sense if they’re not getting enough nutrition from their prey. I think a lot of anglers stopped coming, beginning in around 2015, maybe earlier.”

Searching for solutions

Deciding on the right strategy for controlling the carp wasn’t a simple choice.

“It’s extremely difficult to eradicate common carp with mechanical removal techniques,” comments Ms. Hedrick. “I don’t know that anyone has ever done it, though many have tried. Initially, we had talked about treating just the cove in the spring and other shallow areas, when we know that we’re mostly going to get common carp, instead of treating the whole lake. At that time, the fishery didn’t look terrible, but as time wore on, and we were tracking the fishery and seeing things get worse and worse.” So we got anglers and agency folks together and developed a management plan, in which all parties agreed that we wanted to see the bluegill and bass fishery restored.

A common bluegill. (Credit: Ltshears [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)])

In fact, the team did inquire about collaborating with commercial fishermen, but the remoteness of the fishery made it impossible to survive as a commercially viable enterprise.

“Carp are a non-game species here in Utah, but we encourage folks to try and fish for them anyway because we don’t want them,” remarks Ms. Hedrick. “We try and find ways to make it appealing, because they fight really well, for example, on a fly rod, especially, and it’s a ton of fun. But we realized onsite it was so murky because of the carp, you couldn’t spearfish or bow fish very effectively. This little fishery had changed back to a pond, you know, a mud hole, that nobody cared about. It’s a very important regional fishery. We didn’t want to see that happen and there was a lot of people who also didn’t want to see that happen.”

In the end, the team realized that their choices were limited.

“We really didn’t have very many options, and it just made more sense, if we were really going to make a difference in this lake, to eradicate all the carp and restore the bass and bluegill fishery,” adds Ms. Hedrick. “The only real way to do that is chemical.”

Chemically controlling carp

In 2016, the Pelican Lake Management Team, composed of anglers and agency representatives, decided to remove carp from the lake with a chemical called rotenone.

“It stops the flow of oxygen from the gills to the rest of the body, in any gill breathing organism,” Ms. Hedrick says. “It will hit the aquatic macroinvertebrates, in their aquatic phase, pretty hard, and we’ll see a significant reduction in their numbers, which is why we’ve always tried to keep the chemical out of fishless areas. Off-channel sites where there are no fish, but there should be macroinvertebrates, you don’t treat and allow that area to repopulate the lake with bugs. You want the food base to come back pretty quickly, and it usually does with warmer water temperatures, in my experience.”

However, Ms. Hedrick points out, rotenone is not absorbed by birds or mammals. And of course, soon the fishery will be home to bluegill and bass again.

“We will be restocking soon, pre-spawned fish,” states Ms. Hedrick. “Probably sometime in March or April, depending on when it fits into the work plan and when it’s easiest. We’re holding fish, both bass and bluegill, we salvaged from another regional watershed.”

In fact, the team restocked 2,000 bluegill and 6 bass in December with a couple of transfer days from Steinaker Reservoir. By starting with mostly bluegill, they hope to allow the prey fish to recover without their predators for a year.

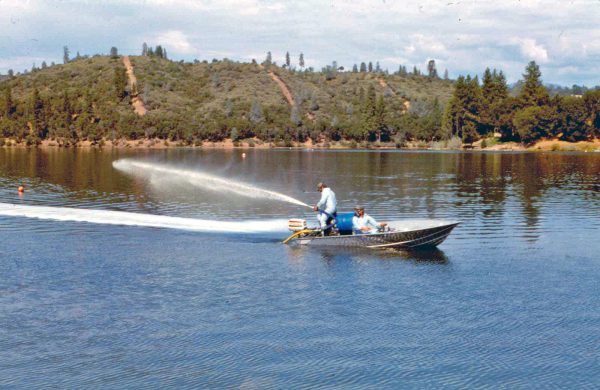

A team applies rotenone to kill diseased trout in a different lake. (Credit: California Department of Fish and Wildlife from Sacramento, CA, USA [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)])

Ms. Hedrick and the other managers will also be monitoring the lake’s water quality.

“Because we received 319 funds from the EPA and our State Division of Water Quality,” explains Ms. Hedrick. “We’ll be monitoring the lake and the changes to the lake.”

The team will also be doing sediment control work at the catchment basin, and some canal improvement and wetland improvement at the inflow.

“The premise is that by repairing these points we can allow less sediment into the lake, and we might hopefully also be able to reduce total phosphorus and pH, which are the two variables that are outside the expected parameters,” details Ms. Hedrick. “Obviously, they want to know that their funding works. So the canal started running November 1st and we’ll be monitoring it every month until it stops running, typically through June, and when it starts running again, we’ll be right back out there monitoring.”

Utah’s Division of Water Quality will also be monitoring water quality parameters regularly using a data buoy—providing critical data for the fishery managers.

“That’s the information, actually, that we use to quantify just how bad it has become, that murkiness,” Ms. Hedrick points out. “I’ve found no instance in the literature where bluegill out-competed carp. It was always carp out-competing bluegill. We hate having to reset a fishery, and you know, although I respect their survival strategy, carp are a pain to manage. If you’re trying to manage for another fishery, they’re a pain.”

Pingback: FishSens Magazine | Stopping the Spread of Asian Carp - FishSens Magazine

Pingback: FishSens Magazine | Stopping the Spread of Asian Carp - FishSens Magazine