Delaware Bay Estuary’s zooplankton getting a closer look for first time in 60 years

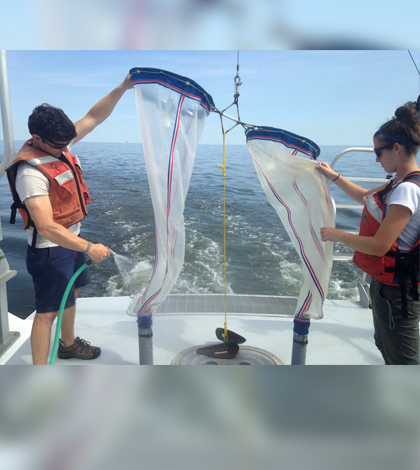

Adam Wickline and Corie Charpentier rinsing down the zooplankton sample after the plankton net has been recovered (Credit: Heather Cronin)

There has been little work done to study zooplankton in Delaware Bay Estuary in the past 60 years. The last comprehensive effort was completed in 1953 by researcher Joanne Daiber at the University of Delaware.

With more study needed, present-day researchers in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean and Environment are undertaking zooplankton surveys in the estuary this year. They’re using net tows, a YSI 6600 water quality sonde and imaging software to amass a visual library of zooplankton that will help future scientists. As the image library expands, water quality data that are collected along the way will reveal what changes the estuary is seeing from climate change.

And there is an old friend helping them too – the work they’re completing is being carried out on the R/V Joanne Daiber. “It’s neat that the boat that we’re using was christened in her name and that we’re doing a reassessment of her study in the bay,” said Jonathan Cohen, assistant professor of marine biosciences at the University of Delaware and principal investigator on the project. But he points out the estuary is pretty neat itself, and is affected by many different land uses.

At several points along its banks, lands are urbanized. Near Philadelphia, runoff from oil operations flows in. But if you go a little further down the bay, large sections of coast are undeveloped, protected by refuges or held in marshy park lands.

Studying the estuary is no walk in the park, but zooplankton, which are an important member of the food chain, provide a good snapshot of its health. “There’s a significant fisheries concern that relies on zooplankton,” said Cohen. “What we want to find out is: Can we develop tools that will allow for quicker assessment of the larvae of zooplankton?”

Adam Wickline transferring a zooplankton sample into a jar for preservation. The sample will later be analyzed with our ZooScan system. (Credit: Corie Charpentier)

A great deal of the work depends on net tows to bring up zooplankton. Cohen and graduate student Adam Wickline are using 200-micron bongo nets with flow meters on them. The nets are deployed about five meters off the bay’s bottom. Using a little geometry, they’re able to take the water’s angle and the net line to find water depth.

The zooplankton they pull up are analyzed and then imaged by a ZooScan optical instrument. Using the library of images that have been amassed so far, pattern-recognition software sifts through the bulk to identify zooplankton types.

“We’re comparing the unknown to the known,” said Cohen. “If we can have a semi-autonomous database for the bay, maybe we can expand it to other bays.” And that, Cohen says, would save other researchers a lot of time. Plus, those using the tool wouldn’t need to be trained experts to identify zooplankton – the database could do it for them.

Alongside the zooplankton tows, Cohen and Wickline are using the YSI 6600 sonde to look at temperature, salinity, turbidity, dissolved oxygen and chlorophyll-a.

“After we finish the net tows, we cast a cage that has the sonde and a hyperspectral radiometer that gives us measurements of downwelling irradiance,” said Cohen. “We’re interested in the light climate throughout the bay because they (zooplankton) vertically migrate up to feed when the sun is down and down when the sun is up.”

The YSI sonde and HydroRad mounted to a cage being lowered into the water (Credit: Heather Cronin)

Levels of chlorophyll-a are important to measure because that’s what zooplankton eat, and Cohen says measurements collected by the sonde will help with other investigations at the university.

“We’re in the early stages of developing a library and getting the ZooScan system going,” said Cohen. And there are few expectations for what they’ll find. “In terms of the gelatinous zooplankton, we may see an increase.”

All the work will inform researchers of changes occurring in the bay. “This can give us a baseline for where we are,” said Cohen. “If we can have this done now, it puts us in a nice position to see how zooplankton are impacted by climate change in this region.”

Funding for the project is provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration through Delaware Sea Grant.

0 comments