Digital Mayfly Data Logger Sensor Stations Monitoring Watersheds

Shannon Hicks and Rachel Johnson from Stroud Water Research Center with installed Mayfly sensor station.(Photo Credit: Stroud Water Research Center)

Shannon Hicks and Rachel Johnson from Stroud Water Research Center with installed Mayfly sensor station.(Photo Credit: Stroud Water Research Center)For most humans, mayflies seem like a nuisance, hovering over the waterways as we try to enjoy them. However, for anyone hoping to monitor the health of watersheds, mayflies are important aquatic species—and now, a digital version of the mayfly is helping some scientists keep an eye on the water. Research scientist Dr. Scott Ensign, who serves as Assistant Director of the Stroud Water Research Center, spoke to EM about how the digital mayfly technology developed.

“Shannon Hicks is the engineer who started developing the Mayfly six or seven years ago,” explains Dr. Ensign. “The Mayfly, which is a printed circuit board, is similar to other open-source hardware such as Arduino because initially, Shannon was using various kinds of off-the-shelf Arduino based loggers.”

However, many data loggers are designed for a wide range of uses, from robotics to the Internet of Things, not specifically designed for someone who wants to connect environmental sensors.

“Since that’s what we’re all about, it was her goal to refine one of those and develop something very specific for connecting environmental sensors to the Mayfly,” details Dr. Ensign. “The Mayfly evolved as an effort to strip away the things that aren’t necessary, and add all the things that you do need, so you have a really convenient device that’s built just for environmental sensors. Shannon has iterated that through multiple stages over time, and continues to refine all of the hardware that’s on that printed circuit board, making it do more, more efficiently, while maintaining flexibility, and without making it overlap with existing off-the-shelf data loggers that allow you to do lots of things but not one thing specifically very well.”

Mayfly data logger on White Clay creek, Pennsylvania. (Photo Credit: Stroud Water Research Center)

Along the way, the team realized that they weren’t alone in their need for this kind of tool.

“That led to the overall effort of EnviroDIY, an initiative out of the Stroud Center, which is designed to enable online communities of people to share ideas for doing environmental monitoring,” Dr. Ensign describes. “The Mayfly serves as a core part of that because again, it’s built specifically for environmental sensors.”

EnviroDIY and do-it-yourself, community electronics

Although the Center’s Mayfly has become the default core of EnviroDIY, there’s no restriction on its use. EnviroDIY is intended to be a community resource to promote DIY electronics.

“The EnviroDIY forum has been a useful tool for people to get together, ask questions, and answer community questions related to using different sensors in conjunction with different data loggers,” emphasizes Dr. Ensign. “Mostly, it happens to be the Mayfly Data Logger on EnviroDIY. Ideally, it provides a home base for people to create a community to help each other, answer questions, and build new things.”

For people who just need a little assistance to get to the next stage, the Stroud Center also offers education.

“That’s part of why we offer additional workshops to folks here in the region, and we also travel,” remarks Dr. Ensign. “This summer we’re in Michigan doing a series of workshops, and we’ve traveled all over to do full-day and two-day workshops to a range of audiences, from teachers to community groups. Trout Unlimited is becoming a big user of the Mayfly and EnviroDIY.”

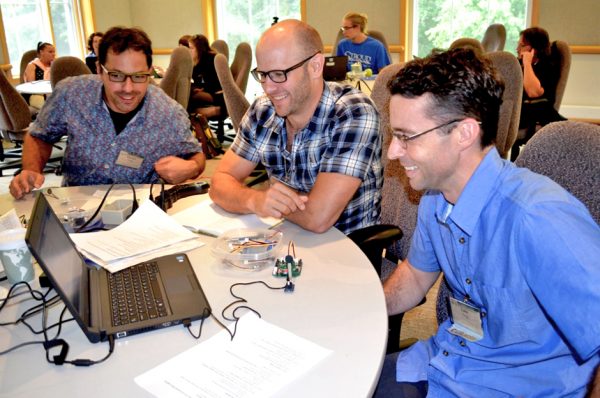

(top and bottom) Workshop participants with Mayfly. (center) the waterproof housing for the Mayfly. (All Photos: Stroud Water Research Center)

The team walks new users through the entire process of deploying the sensors in the field.

“We’ll do a road tour workshop and walk people through the first steps of what the Mayfly is, and how you connect it to your computer and communicate with it,” comments Dr. Ensign. “We show them how to make it do simple monitoring tasks and connect sensors, and then take them through the process of building a fully-fledged sensor station that collects data and sends it online from out in the rain beside a river.”

Right now, to the Stroud team, it seems like more academic users are DIYing it the most—but this may be changing.

“Based on the activity that I see on the forum, my first reaction would be that most of the users are academic researchers,” states Dr. Ensign. “At least the ones that we’re seeing communicating on the forum the most online are graduate students and faculty. There are a few government folks who are using the device too, but I think academic researchers are probably the biggest user, at least in an online way.”

More citizen scientists and commercial users are becoming comfortable with the technology now—and it is available online.

“David Bressler coordinates our Citizen Science Program within our Delaware River Watershed Initiative Project and interfaces with our citizen science teams who deploy the Mayfly Data Logger,” remarks Dr. Ensign. “It’s being used along with commercial, off-the-shelf sensors in a variety of ways to assist citizen science monitoring efforts in the Delaware River Watershed and beyond. We also sell the standalone Mayfly Data Logger board or the Mayfly Data Logger along with a few accessory components—a few very inexpensive but useful educational sensors and a few of the other parts that you can use to expand on the connectivity of the Mayfly—on Amazon. We maintain that Amazon storefront, and we package up the Mayflies and kits and send them. Therefore, we know where those are going to a certain level of detail.”

Watching the digital swarm

Ordering a digital Mayfly from, say, Amazon, lands you with the small, green circuit board that Dr. Ensign has described, the Mayfly Data Logger itself.

“What we focus on in the workshops is outfitting that with a Pelican case, with the solar panel, the sensors connected that are down in the stream behind the device,” remarks Dr. Ensign. “That’s the focus of the workshop, to walk people through the important steps of learning how to do that.”

The Mayfly itself can work with many different sensors.

Participants at Stroud Water Research Center Workshop.(Photo Credit: Stroud Water Research Center)

“As part of the effort, if you go to GitHub, you’ll find hordes and hordes of code that’s been written to connect various sensors to the Mayfly,” Dr. Ensign says. “There is currently code for 35 different environmental sensors written by Sara Damiano and Shannon Hicks at the Stroud Center and Dr. Anthony Aufdenkampe, Beth Fisher, and other contributors to this open-source effort.”

Once users connect their Mayfly to the internet, they can send their data to MonitorMyWatershed.org. MonitorMyWatershed.org is a free data portal which allows anyone to share data online—such as time-series data from sensors that are measuring water, air, or soil—and display them on a map.

“It lets people to discover and view your data, and to do some basic data exploration through a tool there, Time Series Analyst,” adds Dr. Ensign. “That tool enables you to dig into the data, look at different parameters, and create some custom graphical displays of your data. That offers the capability of using the Mayfly to send data to the web in a mappable, open, easily discoverable way for people to share the data that they’re collecting with whatever type of sensors they’re using with the Mayfly.”

Those efforts are linked to an extent through an entirely different online resource called ModelMyWatershed.

“The model, ModelMyWatershed.org, is an online tool for understanding on a watershed basis, land use, land cover—the different features of the landscape such as development that affect runoff and water quality,” explains Dr. Ensign. “It includes a modeling component, with two different types of models. One predicts the amounts of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment coming off the existing landscape. There are also a series of tools for exploring how changes in the landscape, such as different types of cropping techniques or varying degrees of development, would change that runoff.”

Because the Stroud team can mostly see where their swarm goes, and users do often log in, they have a good idea of where the sensors are and how they are being used.

“You can see in the tool the locations where people are sharing data to the Monitor My Watershed portal,” remarks Dr. Ensign. “They’re color-coded with a key that indicates the freshness of the data that’s being collected at those sites. Obviously, there’s a big cluster and intensive monitoring throughout the Delaware River Watershed associated with the Delaware River Watershed Initiative: an effort to monitor environmental quality throughout the watershed and engage different stakeholder groups in collecting data and helping address some of the water quality problems. Stroud participates in that effort.”

Electrical Engineer Shannon Hicks From Stroud Water Research Center Teaching A Citizen Science Workshop. (Photo Credit: Stroud Water Research Center)

The Stroud team has received positive feedback from users.

“I think what it speaks to is the continued and increasing use of EnviroDIY, the forum there, and the addition of new members to that forum over time and the increasing traffic of people contributing,” states Dr. Ensign. “We’re providing a platform, and to some degree, we’re providing the kernel for do-it-yourself electronics and environmental sensing with the Mayfly, but it’s really intended to be an open project and a community-led effort.”

Another technology that has been built into the Mayfly and coupled with Monitor My Watershed to further this community-led goal is the ability to upload data to the web through cellular networks.

“There’s an additional, little board that goes onto the Mayfly, and with a cellular service provider, you can use it to communicate your data back to Monitor My Watershed to post it in real-time,” Dr. Ensign says. “And again, what we’re trying to do is provide an open-source way to share the data. The participant has to pay for the cell service, but the technology to share your data and upload the data is free.”

For some applications and decisions, it’s important to have that data in real time—such as determining when to make a field visit.

“It’s easy to put stuff out, and it’s also easy to forget about it and say, ‘Well, it was there last week, it’s probably good until next week,’” remarks Dr. Ensign. “But the live data gives you the capability to check in on it every day. It’s really easy. You look at your data online and get a sense of whether there’s a problem with the sensors becoming fouled, for example, so it’s time to make a trip out there to clean the lens of the sensor or address a power problem before you start losing data. Having online data, real-time data does definitely increase long-term data quality because it gives you that information to take action before there’s a problem that either leads to poor data or no data.”

0 comments