Future of eDNA could bring easier, low-cost marine species monitoring

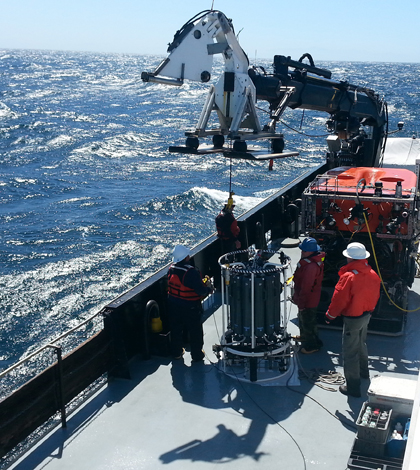

Researchers collect water to test with a new eDNA tool created by the Center for Ocean Solutions that can identify marine species in the water sample. (Credit: Jesse Port)

Jesse Port imagines a future where fishery managers and conservationists might rely on a few quick water samples to determine great white shark populations or human waterborne pathogens, rather than spending dozens of hours and significant resources on traditional monitoring approaches. An early career fellow at Stanford University’s Center for Ocean Solutions, Port believes the key to this feat is environmental DNA, or eDNA, the genetic information left in an environment by animals.

“The approach was well-established prior to this in the world of microbes,” Port said. “It’s been here for a long time… only recently has it been applied to higher organisms: vertebrates, invertebrates, etc.”

Port is a co-author on a paper published in research journal Science alongside scientists from the University of Washington and the University of Copenhagen. The paper proposes the use of eDNA sampling for assessing the biodiversity of marine ecosystems. The microbial studies that Port mentioned focused largely on uncovering new species. The methods proposed in the paper would help researchers, aquatic managers and others locate and quantify known species of concern.

Environmental DNA has been used to monitor aquatic species in the past. University of Idaho researchers tracked amphibians using eDNA sampling, while University of Illinois researchers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service used the technique to monitor the presence of invasive Asian carp in the Great Lakes. But in both of these instances, eDNA was only used to signify the potential presence of a species, and Port says the possibilities could extend far beyond simple detection.

“We’d like to move to a more quantitative application, but we’re just not there yet,” Port said. “It’s probably years in the making, but right now it’s just getting a feel for baseline diversity, learning who’s there and in what relative abundances.”

Science illustrator Kelly Lance’s interpretation of the potential marine diversity represented by the eDNA in a single water sample (Credit: Kelly Lance)

Environmental DNA is often cheaper to analyze and more descriptive than other indicators of a species’ presence. For aquatic applications in particular, the benefits are even more apparent. Many current aquatic species sampling methods are inefficient, require taxonomic expertise, and may be destructive to marine environments. A solitary water sample provides everything eDNA has to offer, though important hurdles remain before scientists can use that information to its full potential.

One problem, Port says, is that it can be difficult to obtain an eDNA sample that is representative of the larger population in an uncontrolled environment. Sequencing and DNA amplification errors are also common issues that can lead to false positive or false negative detections, but they will likely be resolved as sequence data improves. In aquatic applications, the dynamics of oceans and rivers make it difficult to determine from where DNA is sourced. Because of these challenges, eDNA sampling is best used in conjunction with other methods for now, such as visual surveys or trawls.

As the obstacles facing eDNA sampling are overcome, Port says he sees great potential for the technique in monitoring invasive and threatened species as well as tracking shifts in community composition due to environmental and human stressors. As older methods are replaced by cost-effective, non-invasive eDNA sampling, conservation managers could obtain more accurate population figures to inform changes to protective policy. Protective measures enacted under the Endangered Species Act, the Invasive Species Act and the National Environmental Protection Act all stand to benefit from the improved sampling technique.

The bottom line for the rising use of eDNA sampling is simple, Port says: “There are new ways to actually go about doing environmental monitoring.”

Top image: Researchers collect water to test with a new eDNA tool created by the Center for Ocean Solutions that can identify marine species in the water sample. (Credit: Jesse Port)

0 comments