Lake Erie data buoy provides warnings for drinking water plants, data for research scientists

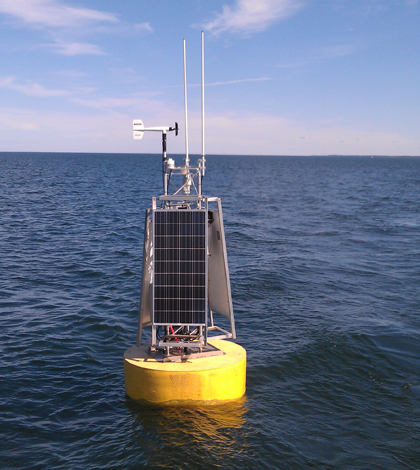

The NOAA data buoy in Lake Erie's off shore waters north of Cleveland (Credit: NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory)

A NOAA data buoy in Lake Erie is giving Cleveland drinking water treatment plant managers an early warning about events that could turn drinking water yellow. Meanwhile, scientists are using the data to learn more about current-related phenomena in the lake that could play a role in pushing low-quality water toward the plants’ offshore intake pipes.

The Cleveland Water Department operates drinking water treatment plants with four intake pipes that range from 3 to 4.8 miles offshore in Lake Erie’s central basin. This area of the lake is prone to seasonal hypoxia brought on by stratification in the spring and summer. The water column separates into an upper layer of warm water over a cooler, denser bottom layer. Oxygen that would normally mix down from the surface can’t pass through the temperature barrier between the two layers.

Decomposing algae depletes oxygen in the lower layer, which can trigger biological and chemical processes that foul the water beyond what standard treatments will fix.

“Once the oxygen goes really low, there’s a change in the makeup of the microbial world and they begin making manganese available,” said Steve Ruberg, a marine instrumentation specialist within NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. “If that gets into the water intake, if it’s not treated with proper warning, it can make the water yellow.”

The hypoxia typically occurs farther offshore than the site of the intakes, but currents and other oscillations of the lake’s water can occasionally move the lower layer of low-quality water closer to shore. That happened in 2006, when hypoxic water passed through the department’s distribution system and generated customer complaints about discolored water.

To help avoid another incident like that, NOAA’s Great Lakes lab has since deployed a data buoy in Lake Erie’s central basin that provides plant managers with real-time measurements of dissolved oxygen near the lakebed, giving them an early warning to ramp up additional treatment mechanisms during hypoxic events.

“It’s something that directly benefits the quality of drinking water for 2 million people,” Ruberg said. “Letting people know when these hypoxic events happen is important.”

Along with the early warning oxygen data, the buoy also carries a string of thermistors that provides a temperature profile of the lake. That data supports research into Lake Erie’s internal waves–oscillations that occur near the temperature boundary in 18-hour periods that may play a role in moving hypoxic water over the intakes.

In addition to the buoy data, the scientists also keep tabs on the movement of hypoxic water with satellite imagery and a circulation model. The model is particularly useful for keeping track of a phenomenon in which wind-driven, west-moving currents, in combination with the planet’s rotation, can shove the degraded cold layer toward Cleveland.

“If you have strong enough northeast winds to cause west-moving currents, you then have a situation where the Earth’s rotation actually moves the water mass to the north, and the cold water layer can get pushed into the water intake,” Ruberg said. “The Earth’s rotation affecting the change in direction of the currents, that’s something that would be unique to oceans or large bodies of water like the Great Lakes. It wouldn’t happen on a small lake.”

0 comments