Learning at Biological Field Stations Across America

Dr. Jill Zarestky, Assistant Professor, School of Education, Colorado State University, (Credit: https://fieldstationoutreach.info/the-team)

Biological field stations (BFS) are invaluable tools for researchers whose work takes them outside. But they’re also filled with opportunities for the general public—and when laypeople learn about science and nature at biological field stations, everyone benefits. EM spoke to Colorado State University assistant professor Jill Zarestky about her recent research on the ways learning happens at BFS across the US.

For Dr. Zarestky, the work began with questions she and her colleagues couldn’t answer. For example, they wanted to know how field stations were approaching outreach, but they didn’t know, and there was no literature on the subject.

“I don’t necessarily mean biological research questions,” clarifies Zarestky. “I mean the fundamental issue of what should education for the public look like at field stations? What are ways to do that well? And that brought us to bigger questions about how the missions of field stations and educational opportunities connect.”

All scientists ask questions; that’s what research is all about. But that’s not the kind of question that was bothering Dr. Zarestky and the team.

“A lot of this stemmed from questions that Rhonda [Struminger of Texas A&M] was having about what they were doing at their research station in Mexico that people in the bio-science disciplines couldn’t answer,” explains Dr. Zarestky. “[Collaborator] Michelle Lawing is a bio-scientist and she calls herself a field station groupie. For me in education, I had a lot of questions myself, but also no answers. We came together with the social science, the natural science, and the practical experience to address these questions from a place of needing practical answers.”

Educational outreach at biological field stations

At the beginning of their research, the team saw educational outreach happening at various BFS, often in informal ways.

“We saw a lot of folks doing educational outreach because the field station personnel, the scientists, and the staff think it’s fun, and they want people to know about their field station,” details Dr. Zarestky. “Or they’ve got NSF funding and have some broader impacts obligation to address, so there was this funding requirement. But whether it’s fun, or because you have to—there’s more to it than that. What purpose does it serve in the bigger picture of the field station’s operations?”

The researchers wondered how to modify the language we use to describe biological field station missions so that their educational components could be part of the “baked-in” design instead of tacked on at the end for whatever reason.

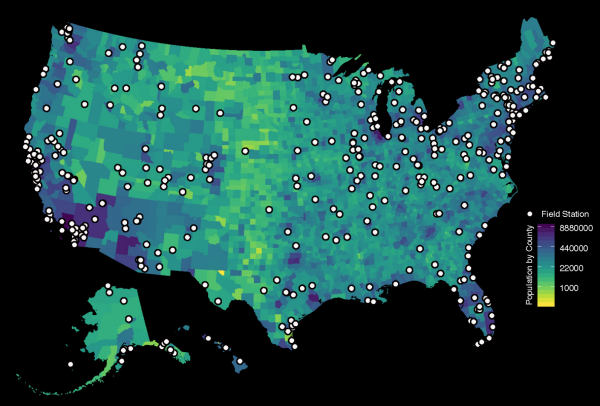

Map of biological field stations in the US. (Credit: Struminger et al., Bioscience, https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article-abstract/68/12/969/5114605?redirectedFrom=fulltext)

“If people could see how educational outreach for the general public connects to the mission of the field station, that it’s not just a fun sideline or a thing you have to do for your funding requirements, then it becomes a thing that can benefit the field station as a whole in fulfilling its research mission and connecting the field station to its local community and other stakeholders,” states Dr. Zarestky. “We can think about our experiences at field stations as opportunities for the general public to learn science by connecting to nature. Those are big, worthwhile things that deserve some real attention.”

The outstanding question became: how?

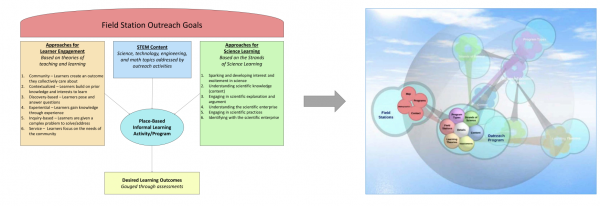

“A lot of our work at this point, including the conceptual framework, has been helping people think through their educational outreach with a baseline of intentionality,” remarks Dr. Zarestky. “You can do whatever you want to do, but first figure out what it is that you want to do, and then design to achieve that purpose.”

This begs the question: what are BFS across the country doing now? Is it consistent from place to place? Should it be?

“One of the things that’s particularly interesting about field stations is that they cover the entire spectrum of possibility,” comments Dr. Zarestky. “There are field stations who employ teams of professional educators who do excellent work; they’re knocking it out of the park and have a lot that other stations could learn from. And then there’s the one-person-shows where somebody is trying to do everything at a field station all by themselves. That spectrum of possibility and expertise and resources I think connects to the spectrum of who’s winging it and who’s got it figured out.”

Zarestky and the research team don’t profess to have the answers but assert that some of the key work that researchers can do is to make connections with each other so that people working in BFS are aware of the resources that are available to them.

“For example, you want to do a program for third graders on water quality. Perhaps someone at another station already has one of those. Ideally, you could talk to them and support each other,” adds Dr. Zarestky. “There’s a lot of really excellent stuff happening, and some people in the BFS community don’t know where to turn for support or help. If some of this work can create those resources then everybody benefits.”

Moving ahead to meet the challenge

The team’s pilot study results are published in a recent paper, but the full scale-up is still running.

“The data in the published paper was from 20-some stations, and now our current and ongoing study is over 160 stations with over 350 educational programs across the country,” explains Dr. Zarestky. “We learned from that pilot study that the issues were just so much more complex than we were able to capture in that smaller sample. We really needed to figure out a way to capture some of that complexity.”

The ongoing challenge right now is how to process the diverse data.

Informal STEM learning framework based on survey results (left; Struminger et al., Bioscience). The framework will be transformed into an online wiki (right) for the outreach community. (Credit: Struminger et al., Bioscience, https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article-abstract/68/12/969/5114605?redirectedFrom=fulltext)

“We’ve got data on field station descriptive characteristics, funding, distribution of resources, number of personnel hired, number of programs run, training, all the different design elements of a program,” details Dr. Zarestky. “It’s so complicated that it’s a little bit slow for us to see patterns emerging. I think the biggest surprise is how much diversity there is in these programs. To accurately process the data in a way that we can make sense of things that matter to the people who represent all of this diversity, has been really a learning experience for the research team.”

Ideally, the team sees their work helping to usher in a new, two-pronged approach to field stations. Not only is a BFS a piece of scientific infrastructure that needs investment, but a BFS is also a human resources investment, which will demand skill building and mentoring.

“I think the thing that we’ve come back to is that we really need a body of professional development resources,” remarks Dr. Zarestky. “We can’t create solutions to individual problems. But we can think about what kind of problems people might run into, and try to create some generalized starting point solutions. From the data we’re analyzing now we’re getting some good, big picture ideas of how complicated it is; the next step will be figuring out how to turn that into resources field station personnel can use to do a better job with their educational outreach based on whatever a better job means for them in their field station.”

The team is already convinced of one thing: there is certainly a need for their research.

“That’s part of why the project is so well received by the Field Station community,” states Dr. Zarestky. “To have an almost 50 percent response rate on a survey that can take about 2 hours—people don’t do that unless they see the value of it. I think there’s a real need for this in the community and that community is becoming acutely aware of it.”

The larger public also has a lot to gain from well-equipped biological field stations staffed with people trained to educate.

“One of my favorite findings was that approximately 78 percent of the U.S. population lives within 60 miles of a biological field station, and 98 percent lives within 120 miles,” emphasizes Dr. Zarestky. “Most field stations want people to come visit. They want to show off their science. Field stations exist in these sites because they are unique or important in some way, and that’s worth knowing about. This is just a tremendous opportunity and I think we have a lot more bandwidth to increase.”

“I’m hoping that some of the value of this work is going to be helping scientists think a little bit more about how they can leverage their research and their space to connect with people,” adds Dr. Zarestky.

Top image: Jill Zarestky, Assistant Professor, School of Education, College of Health and Human Sciences, Colorado State University, (Credit: https://fieldstationoutreach.info/the-team)

0 comments