Michigan Tech’s ROUGHIE gliders will follow their own path

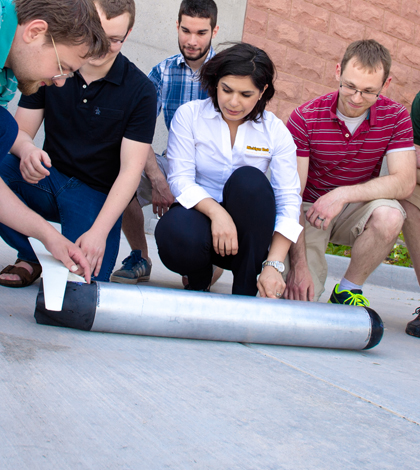

Nina Mahmoudian and students from her lab along with the ROUGHIE glider prototype. (Credit: Sarah Bird/Michigan Tech)

Autonomous underwater vehicles only operate on their own after they’ve been programmed, following the plan and survey course they’ve been given. This is good for monitoring and data collection, but existing AUVs are less ideal for locating items lost underwater.

Researchers at Michigan Technological University are working to solve that problem by developing gliders that operate more independently and are capable of knowing what their search target is. If the new AUVs work well, scientists and disaster-response teams could use them to pinpoint the locations of pipelines, cables or sunken vessels more quickly than is possible today.

Nina Mahmoudian, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, has spearheaded the gliders’ design. Along with graduate and undergraduate students from her lab, she is getting ready to test gliders named with the acronym ROUGHIE, for Research Oriented Underwater Glider for Hands-on Investigative Engineering.

Key to making the devices capable of searching underwater environments on their own is an integrated navigation sensor system that allows them to use situationally aware search algorithms. A modular design allows for many environmental sensors to be deployed at a time and internal components can also be swapped in or out for tests or service.

Testing the ROUGHIE prototype in the Portage Waterway (Credit: Sarah Bird/Michigan Tech)

Each ROUGHIE is three feet long and weighs only 25 pounds, making them one-person deployable and retrievable. With their small size, Mahmoudian sees ROUGHIEs as being most useful in shallow water regions where they can be used to map currents, measure coastal pollutants or monitor around harbors and ports. Four of the vehicles should be ready for testing in December 2014.

“A ROUGHIE fleet will give me the opportunity to implement the efficient-motion planning algorithms I have developed,” said Mahmoudian. By using those algorithms in real-world environments, she hopes to learn what adjustments need to be made so that they better account for challenges that arise.

The Portage Waterway, which sits beside Michigan Tech in Houghton, Mich., is the ideal proving ground. Mahmoudian plans to use the deep commercial waterway to run the gliders through real-world conditions like strong currents, low visibility and high sediment loads. The passage also sees steady vessel traffic and several underwater cable and pipeline crossings.

“Robust winter ice cover, as a direct surrogate for polar regions, makes our test site unique and highly valuable,” said Mahmoudian.

ROUGHIE in the Portage Waterway (Credit: Sarah Bird/Michigan Tech)

The Michigan Tech team is working out the kinks with a functional prototype before building a fleet of four. Mahmoudian says they are working through small tweaks, reconfiguring some parts and making new ones along the way to finalizing the ROUGHIE design. With the gliders’ advanced tech, they’re still aiming to keep costs down so that each one runs about $10,000.

Building the four gliders is supported by a grant from the Office of Naval Research.

Top image: Nina Mahmoudian and students from her lab along with the ROUGHIE glider prototype. (Credit: Sarah Bird/Michigan Tech)

0 comments