Monitoring the Lake-shaping Plant Growth in Lake St. Pierre

A diver collects plants from Lake St. Pierre. (Credit: Patricia Bolduc)

A diver collects plants from Lake St. Pierre. (Credit: Patricia Bolduc)Researchers in Quebec are taking underwater photos to get a fish-eye view of lake-shaping aquatic plants. They’re proving the use of a technique that could expand the study of plant populations that impact everything from a lake’s plankton and fish populations to its water levels.

Photo analysis could replace more expensive and labor-intensive methods.

“If you want to have good data, you have to dive and collect plants and dry them and weigh them,” said Andrea Bertolo, a professor of environmental science at the University of Quebec at Trois-Rivières. Soon, anyone with an underwater camera and a selfie stick could be contributing to this valuable science.

Bertolo, along with his graduate student and the principal investigator, Patricia Bolduc, outlined their new method and findings about the relationship between plant communities and zooplankton diversity and size in research published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research in January.

Proving that cheaper also means accurate

“The goal of the paper,” Bertolo said, “was to find a way to assess plant biomass in a more cost-effective way.

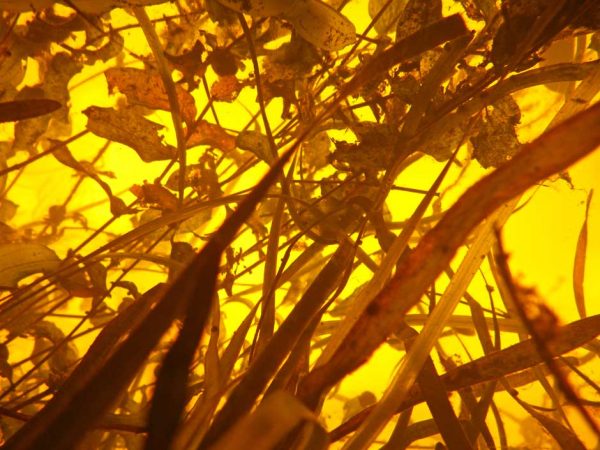

Researchers dive to gather information about plant diversity and abundance in Lake St. Pierre. (Credit: Patricia Bolduc)

They took the photos back to the lab, counted the pixels that contain plants and those that contain sky (as seen through the water) and found a measure of plant cover and abundance. Averaging the plant cover from the photos taken at different points around the boat provides measures of plant abundance that are nearly as accurate as those gathered by divers who collected plants in the area directly after. Similar photographic methods are used in forestry to determine tree cover in an area of forest, Bertolo said.

Researchers can also use these photos to assess plant diversity by identifying different leaf types and structures in the photos.

The manual nature of this photo analysis means that the work is still relatively labor-intensive. But that could change with applications of deep learning, which could allow computers to identify the differences in color or leaf shape on their own, Bertolo said.

Full automation of the analysis process is complicated, Bertolo said. Because water can be crystal clear, cloudy or anywhere in between, it can be difficult for standard computer tools to tell the difference between plant and sky, which could appear differently colored from day-to-day.

The process could be even easier, using selfie sticks and cheap underwater cameras.

Divers taking upward-facing photos of aquatic vegetation is a cheaper and easier method of estimating plant abundance and diversity in lakes. (Credit: Patricia Bolduc)

Instead of diving, researchers would only need to pilot a boat above the area they want to monitor, submerge the camera to a standard depth and take photos from several spots around the boat.

Citizen scientists could expand understandings of lake health

With faster, automated analysis of photos and the involvement of citizen scientists, aquatic plant monitoring could greatly expand.

Bertolo suggested that people who live or vacation yearly on lakes could easily help create a long-term series of photos that provide information about the microscopic communities there and the spread of invasive species.

This research found that more plants meant more and bigger zooplankton, Bertolo said. Bigger plankton more effectively control phytoplankton populations by grazing. Plants provide shelter to zooplankton that might be eaten in the open.

The researchers also tested whether plant structural diversity led to zooplankton diversity by providing more types of shelter. They found that it was an important predictor of zooplankton diversity.

Plant life shapes lake life

Aquatic vegetation determines more than just plankton populations though.

In research published in the Science of Total Environment in May, Bertolo and another graduate student, Matteo Giacomazzo, found that declines in plant abundance in Lake St. Pierre corresponded to declines in the lake’s yellow perch fishery. Since about 2000, plant abundance and yellow perch have been declining. Commercial and sport fishing of yellow perch in Lake St. Pierre was banned for five years in 2012. In 2017, the ban was extended until 2022.

Analysis of underwater photos like this can provide accurate measures of plant abundance and diversity. (Credit: Patricia Bolduc)

Gauging historical plant abundance is difficult. To do so, the researchers used the fact that plants hold back the flow of the lake, which is part of the St. Lawrence river system.

Before plants begin to grow in earnest for the year, around April, there is a natural drop in water level of 40 centimeters from the lake’s inlet to its outlet. When plant growth reaches its peak, the difference can be closer to 90 centimeters. Because water level data goes back to the 1930s, they had a rough estimate of plant growth for the lake reaching back decades to compare to fish population records the government has kept for years.

The downward turn of plant abundance and yellow perch populations in 2000, matched an increase in the lake’s turbidity that started at that time, Bertolo said. The increased cloudiness was cutting plants off from the sun.

All these connections tell a compelling story of the changing ecology of the lake, even though the estimate for plant abundance isn’t based on clear, specific records of plant abundance throughout the lake, Bertolo said. A long-term record of plant abundance from specific locations throughout Lake St. Pierre, and many others, doesn’t yet exist.

With cheaper, faster and more accessible strategies for monitoring aquatic plant life, a long-term, specific record could be within reach.

0 comments