New Standards Target Perfluorinated Compounds in Colorado

Senior Airman Allen Stoddard, 60th Civil Engineer Squadron, blows a small sea of fire retardant foam that was unintentionally released in an aircraft hangar at Travis AFB, Calif., Sept. 24, 2013. The non-hazardous foam is similar to dish soap and eventually dissolved into liquid, which was helped by high winds. The 60th Air Mobility Wing firefighters helped control the dispersion by using powerful fans and covering drains. No people or aircraft were harmed in the incident. (Credit: U.S. Air Force photo/Ken Wright/Released)

The State of Colorado has recently adopted new standards targeting perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) in water. The change rests on the events of the past few years, during which the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) instructed states and municipalities to investigate their public water systems for these PFCs. Federal Facilities Remediation and Restoration Unit Leader Tracie White with the Hazardous Materials and Waste Management Division (HMWMD) of the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment (CDPHE) discussed the change in standards with EM.

Perfluorinated compounds in focus

Perfluorinated compounds are a group of human-made chemicals. Developed for use in products that resist heat, grease, oil, stains, and water, PFCs do not occur naturally in the environment. They are frequently found in coating additives, cosmetic products, dental floss, certain types of food packaging and clothing and carpet surface protection products. PFCs can also be found in firefighting foams; in fact, that was how they came to contaminate the water in this case.

As you might guess based on how common it is for products to contain PFCs, human contact with these compounds is widespread. Principally, people and PFCs come into contact via personal care products and food; almost all people have detectable levels of PFCs in their blood.

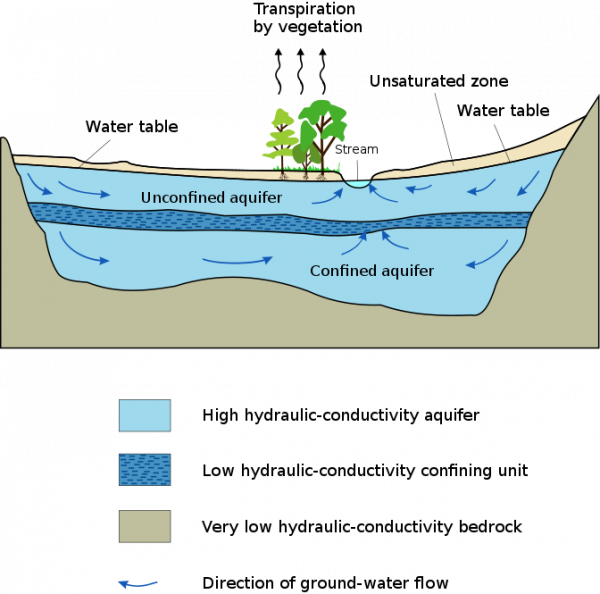

This also means that perfluorinated compounds are routinely released into the water supply and the environment more generally. As compounds settle, they seep into aquifers and other places where water is sourced for consumption. The EPA took this issue on in 2013 and 2014, requiring states and cities with large public water systems across the nation to collect water samples and test for PFCs as part of the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UMCR).

The UMCR is a national monitoring program developed to determine where unregulated substances enter drinking water sources and in what amounts by gathering data. In this way, the EPA monitors a range of substances to determine whether they should be regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). This national monitoring effort detected PFCs in 108 water supply sources across the country, and the EPA issued a new health advisory concerning PFCs on May 19, 2016.

PFCs in Colorado

On April 9, a Colorado state water panel adopted new standards for PFOS and PFOA, two varieties of PFCs. The standard is 70 parts per trillion for each PFOS and PFOA. This site-specific standard for groundwater quality was proposed by the CDPHE’s HMWMD, correlating with the May 2016 EPA Health Advisory. As yet, there are no federal EPA PFOA or PFOS standards for drinking water or groundwater.

“The EPA’s third unregulated contaminant monitoring rule (UCMR 3) required testing for 30 unregulated contaminants—28 chemicals and two viruses,” explains White. “Six per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were on the list, including perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS), perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA). As a result of this testing, we discovered the PFOA and PFOS contamination.”

Aquifer diagram. (Credit: © Hans Hillewaert/Released [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.)

“The boundary for the site-specific groundwater standard encompasses the contaminated aquifers, as well as the hydrologically connected alluvial channels,” adds White. “Facilities in the area affected by the site-specific groundwater standard will be required to sample for these contaminants and address them, as required.”

The monitoring should start the first week in July and will adhere to EPA protocols.

“Barring any unforeseen administrative issues, the site-specific groundwater standard for PFOA and PFOS will become effective on June 30, 2018,” details White. “The turnaround time for sample results will vary, as a function of the laboratory. EPA Method 537 typically is used.”

EPA Method 537 dictates that liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) is the preferred technique for detecting selected perfluorinated alkyl acids (PFAAs) in drinking water. There are no plans to change wastewater treatment processes at this time.

As of February 20, 2018, PFOA and PFOS were listed as Appendix VIII hazardous constituents by the Colorado Solid and Hazardous Waste Commission in the Colorado Hazardous Waste Regulations. The listing, which became effective on April 14, 2018, requires facilities to monitor and take necessary corrective actions, giving regulators the authority to hold polluters accountable and require cleanups to a safe standard.

One final technical detail in the mix for those doing the monitoring is the problem of contamination, as White points out.

“Given the presence of PFAS in many common consumer products and equipment often used to collect soil, groundwater, and surface water samples, together with the need for very low reporting limits, great care needs to be taken during sampling, to avoid sample contamination,” remarks White. “Sources of potential contamination during sampling may include Teflon™ and other fluoropolymer-containing materials, waterproof/treated paper or field books, stain-resistant and water-resistant clothing, Tyvek material, aluminum foil, personal care products and food and beverage wrappers/containers.”

Top image: Senior Airman Allen Stoddard, 60th Civil Engineer Squadron, blows a small sea of fire retardant foam that was unintentionally released in an aircraft hangar at Travis AFB, Calif., Sept. 24, 2013. The non-hazardous foam is similar to dish soap and eventually dissolved into liquid, which was helped by high winds. The 60th Air Mobility Wing firefighters helped control the dispersion by using powerful fans and covering drains. No people or aircraft were harmed in the incident. (Credit: U.S. Air Force photo/Ken Wright/Released)

0 comments