Satellites and sensors track ice-out timing on Alaska’s lakes

Ice-covered Lake Teshekpuk on Alaska's Arctic Coastal Plain as seen from NASA's Terra satellite on June 6, 2012 (Credit: NASA)

The timing of ice breakup on the frozen lakes and rivers across Alaska has a cultural significance in the state. Take for example the Nenana Ice Classic, a 97-year-old contest to guess the exact time a big black-and-white tripod set out on the frozen Tanana River will break through the ice. Last year’s winning guess of May 20 at 3:40 p.m. was good for a $318,000 jackpot.

But the ice-out date has broader implications than big bucks for good guessers.

“It’s a pretty good indicator of changes in the timing of spring or the timing of fall, and it’s been linked to changes in climate,” said Christopher Arp, associate research professor in the Water and Environmental Research Center at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. “Also, it’s a process that is responsible for how ecosystems on the landscape operate.”

And in a state with regions where lakes make up 40 percent of the land cover, it’s a process worth keeping track of. Arp and other researchers are using satellite data and ground-based sensors to track the ice-out date on dozens of lakes across the state. So far, they’ve gathered 7 years worth of data that will serve as a baseline for future studies and contribute to ice-out phenology modeling.

Ice-out’s physical influences on the landscape include effects on energy balances. Iced-over lakes reflect around 90 percent of solar radiation, while open water absorbs around the same amount. Biological influences include rising water temperatures the drive productivity and trigger fish behavior. Ice-out also makes the lake surface available for wildlife like migrating waterfowl.

Arp and colleagues kept track of ice-out dates by visually inspecting images collected by NASA’s MODIS Terra satellite. They ground-truthed the satellite observations and monitored lakes too small for MODIS to resolve with sensor stations on dozens of lakes across the state.

Scientists embarked on snowmobiles to deploy sensors on lakes in the Minto Flats region (Credit: Guido Grosse)

Some of those stations are made up of a temperature- and light-sensing data logger attached to line running between an anchor and a surface buoy. The researchers set the rig out on the frozen lake, and when the ice breaks up the anchor drags the sensor down to the bottom. When the researchers go back and look at the data, they can assume the ice broke up on the day that light level readings dropped to near zero and the temperatures lose the daily variation driven by daylight cycles.

Other lakes are outfitted with temperature sensors on the bed and at the surface. For that system, ice out is indicated by the bed temperatures gradually rising and then quickly dropping to zero degrees when the ice-free lake mixes. Surface temperatures, on the other hand, hover around zero before rising quickly after ice out.

Arp said those sensors are deployed in April during weeks-long snowmobile expeditions made necessary by the lack of roads in areas like the Minto Flats. On a recent trip on the North Slope, Arp said they put around 800 kilometers on their snowmobiles, which pulled sleds full of fuel and field and camp gear.

They retrieve the data loggers in August via float plane, returning to the GPS coordinates marked when the buoys were deployed. But shifting, broken-up ice can drag buoys across the lakes, complicating retrieval.

“There are definitely some issues with relocating some of those buoys,” Arp said. “If they get moved, we have to circle around the area with a float plane and look for them. Sometimes we don’t find them, but most the time we do.”

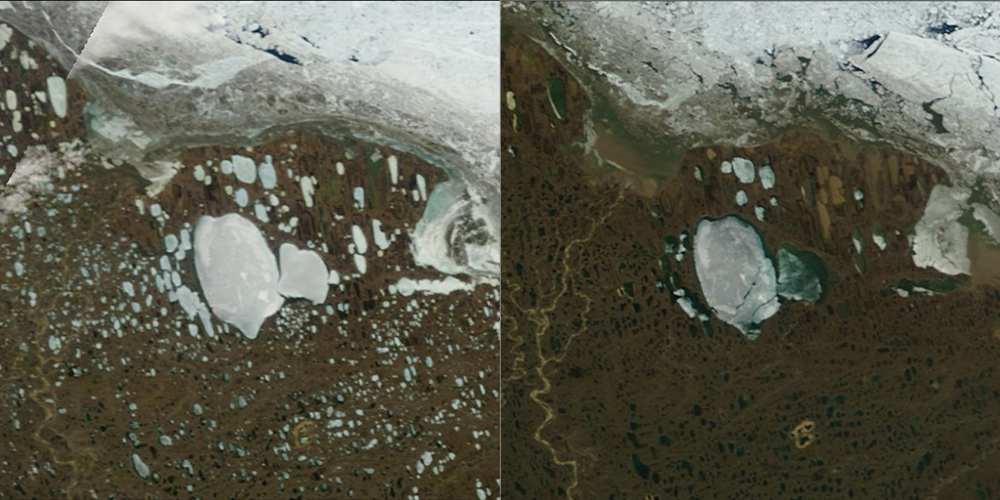

Images from NASA’s Terra satellite show the difference in ice cover from June 21 to July 4, 2012 (Credit: NASA)

So far the data has shown little year-to-year variation in ice-out date, which ranged from May 7 in southern Alaska to July 6 on the Arctic Coastal Plain to the north. The exception was the spring of 2013, which came much later than usual and kept lakes frozen longer. It also made for the latest-ever tripod fall for the Nenana Ice Classic.

Just as the late spring was a boon to the jackpot winners, it also helps scientists modeling ice-out timing.

“Having observations that are more similar to what we saw in the past are really helpful to informing those types of models and developing more accurate hindcasts of those records,” Arp said. “Now if we could get one that’s a really early ice out, that would really help us.”

Top Image: Ice-covered Lake Teshekpuk on Alaska’s Arctic Coastal Plain as seen from NASA’s Terra satellite on June 6, 2012 (Credit: NASA)

0 comments