Predicting and Responding to Wildfires: Canada’s Scientific Approach to Fire Management

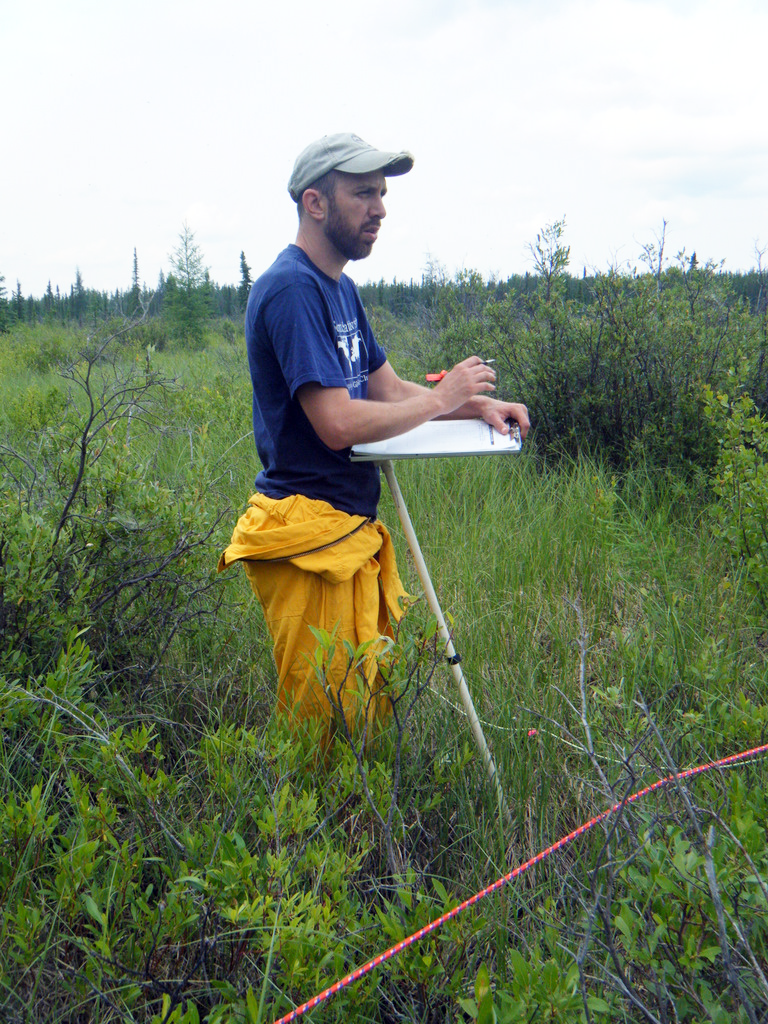

NRCan researchers conducting fieldwork in Nahanni National Park Reserve, Northwest Territories (Credit: NRCan)

NRCan researchers conducting fieldwork in Nahanni National Park Reserve, Northwest Territories (Credit: NRCan)High temperatures and prolonged dry spells lead to increased chances of wildfires sparking across the world. In order to combat fires, federal and local governments have developed fire management programs and policies to prevent and respond to wildland fires. Many of these policies and strategies are influenced by research emerging from scientists that study landscapes across the world.

In Canada, Marc-André Parisien, a research scientist for Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), spends his days surveying and sampling forests to help better understand wildfires and inform future management. Over the past 23 years, Parisien has worked to help compile and understand foundational data on wildland fires. He explains, “The better we understand them, the better we can live with wildfire.”

Beyond fire research, NRCan works on a range of initiatives that support operations and help develop policies in provinces and territories. While research is conducted across the country, land management is relegated to the respective province and territories, not the federal government. As such, it is the responsibility of the Canadian Forest Service to guide and support local initiatives through research, funds and guidance.

How Canada Monitors Forests and Wildfires

Canada monitors above and below the tree line to survey land and monitor fires. In terms of ground monitoring, forest inventory plots are used to sample vegetation and assess forest health. Vegetation sampling in these plots can explain the composition of the forest in terms of species and structure.

Parisien expands, “So how big are the trees? Is it an open forest? Is it a closed forest? Is there a big shrubby layer or it’s just wall to wall, kind of like tall, thick trees? Those kinds of things. So it’s fairly detailed measurements to get to the composition and structure of this forest.”

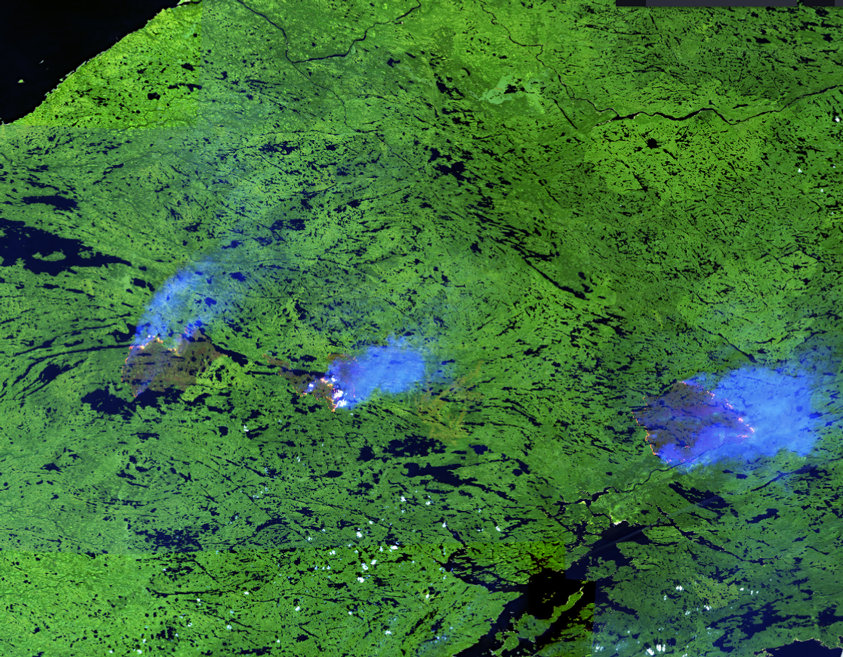

Data gathered can be used to predict the likelihood and severity of fires—it all depends on what is being predicted. In some case, ground monitoring may be necessary, while other circumstances may be better suited for monitoring from the sky. Satellites provide imagery of the environment from above and can capture much wider visualizations of fires and forests.

“It always depends what you’re predicting, right? If you’re predicting something that’s supposed to happen tomorrow, then you can use very detailed weather data, weather forecasts, and things like that. If you’re trying to predict a wildfire that may occur over the next 20 years you can use different types of information but it’s all based on what drives wildland fires,” states Parisien.

Parisien conducting fieldwork in Wood Buffalo National Park, Alberta and the Northwest Territories. (Credit: NRCan)

Weather monitoring is also a significant part of fire prediction as fire-conductive weather, like hot, dry and windy conditions, can create an ideal environment for a wildland fire. Once the fires have been ignited, flammable vegetation allows the fire to spread. Surveying and documenting the percentage of flammable vegetation, also known as fuels or the flammable portion of the biomass, is another way to study and predict wildfires. In hot and dry years, more vegetation is likely to be considered a fuel, allowing wildfires to spread further.

While the satellites help provide greater insight into how far-reaching everything is, they provide limited information on what’s going on at the ground level. The combined use of satellite imagery and ground monitoring allows researchers to build a better understanding of forests.

“There is a variety of ways that we can measure what’s going on in the forest and then evaluate the health of the forest or things like tree regeneration, how these forests progress through time and are affected by the various disturbances and changes in climate,” says Parisien.

Causes of Wildfires and How to Prevent Them

In a typical year, the majority of large wildfires are usually ignited by lightning strikes in remote areas, igniting available fuel sources. This year’s fire season was unique in that a majority of the first wave of wildfires in the spring and early summer were presumed to be human-caused since there was no evidence of lightning strikes or links to a holdover fire.

“The warmer the atmosphere is, generally the greater the convective and lightning activity. So that makes a lot of sense. But then, in terms of human caused ignitions, many, many, many of these are preventable. And it’s a little bit disappointing to see how many of these large fires we have at this stage,” Parisien explains.

The responsibility of wildland fire response and prevention are both assigned to individual provinces and territories, but many of them include similar strategies as a result of the comprehensive wildfire information provided by NRCan. Management approaches like prescribed burns and sustainable land use are two strategies recommended by NRCan and often deployed locally in provinces.

To support these initiatives and contribute to the greater understanding of wildfires, NRCan monitors, maps and predicts wildfire occurrence—all of which is shared with the public through the Canadian Wildland Fire Information System.

The data gathered by researchers like Parisien helps provinces develop more comprehensive plans and increase public awareness. “The research is essential because it leads to tools that help the broader public to understand and map, wildland fire risk, those kinds of things,” states Parisien.

Sentinel-2 imagery of wildfires in Quebec. (Credit: NRCan)

Conclusion

Depending on characteristics and location, fires aren’t always suppressed. Parisien explains, “Some wildland fires get full fire suppression treatments—so kind of hit them hard and hit them fast—and others that ignite in remote areas that are not a threat to communities are often not actioned.”

If the isolated fires spread toward communities or other infrastructure, then the province will move to suppress them. Parisien continues, “There’s a lot of priority setting that is going on when you have so many fires burning, as is the case right now.”

Canada’s fire season this year was particularly severe, with the greatest area burned on record since they started measuring wildfires. While the beginning of the season was largely connected to human-caused fires, a majority of the fires that occurred later were caused by lightning strikes.

Even though this season has been particularly active, Parisien notes that previous years demonstrate a trend of fewer human-ignited wildfires on average, contrasting the increasing trend in lightning-caused wildfires in some areas. While human-caused ignitions can hopefully be reduced through awareness and education, naturally caused fires are a result of environmental variables that will continue to change.

0 comments