Wildfire’s effect on endangered Houston toad milder than feared

Male Houston toad (Credit: Donald Brown)

After a 2011 wildfire in Texas burned through much of the endangered Houston toad’s remaining habitat, scientists and managers doubted many amphibians survived and assumed the land was spoiled as a home for toads.

But as the scientific process bore out, some unexpected results surprisingly revealed a rare piece of good news for the toad’s future.

A study published recently in the Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management suggests that, two years after the Bastrop County Complex Fire, climatic variables like temperature and soil moisture — important controls on amphibian habitat — did not differ significantly between burned and unburned lands.

That was a surprise to Donald Brown, wildlife ecologist and lead author of the study.

“I had a lot of ideas going in, most of which did not bear out in the results. Pretty typical for me,” Brown said. “I guess you can say that’s the fun thing about science: You prove yourself wrong all the time.”

The fire was the most destructive in Texas history in terms burned structures, and killed nearly all the living trees across 40 percent of the Lost Pines ecoregion, an an isolated population of loblolly pines that make up the western-most edge of the species’ distribution. The fire burned all of Bastrop State Park, which Brown said is “ground zero” for the federally endangered Houston toad.

The fire burned more than 34,000 acres, killing around 80 percent of overstory trees and eating through pine litter that had piled up more than a foot deep in some places.

“All of a sudden you’ve got bare ground — nothing, no vegetation — and a dead overstory,” said Brown, who conducted the study while a doctoral student at Texas State University-San Marcos. “It was a dramatic change in the landscape immediately post-burn.”

The Lost Pines ecoregion post-fire (Credit: Donald Brown)

Brown, now a post-doc with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wanted to know the effects of those changes on the local climatic variables that can influence an amphibian’s ability to preserve moisture. That was driven by his interest in the Houston toad, which is endemic to East Central Texas and is in severe decline. Extirpated from Houston in the 1960s, it was among the first cohort of amphibians listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1973, though that failed to spur much action.

“This is a species that was essentially listed and forgotten about for 30 years,” Brown said.

Michael Forstner, professor of biology at Texas State, co-author of the study and Brown’s adviser while he a student there, picked up research on the species around 2000.

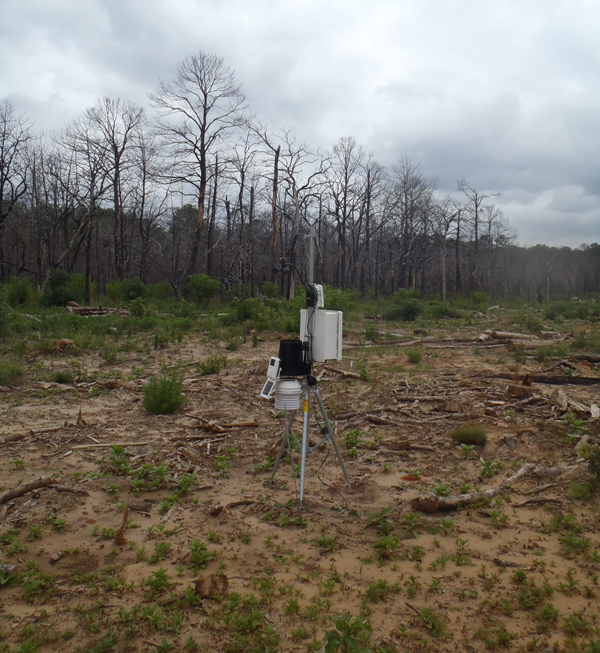

For this study, Brown acquired two portable weather stations from Davis Instruments to measure air temperature, humidity, wind speed, and soil temperature and moisture. The stations were used to measure variables in burned and unburned areas in Bastrop State Park and Griffith League Ranch, two properties that the Houston toad will likely depend on for its recovery. The researchers also measured the same variables within burned areas that had been clearcut and areas where dead trees were left standing.

Portable weather station in a clearcut area of a burned region (Credit: Donald Brown)

The results showed that both maximum and average wind speed was higher in burned and clearcut areas. But air temperature, humidity, soil temperature and soil moisture did not differ between burned and unburned areas, or between clearcut and uncut areas.

Brown speculated that the extreme drought conditions that persisted throughout the study period may have had something to do with the results, especially in terms of soil moisture: It was just very dry everywhere.

Along with post-fire population surveys that have turned up live toads within burned areas, studies have so far produced results that were unexpected but quite welcome.

“In terms of conservation, that’s a good result to get,” Brown said. “You don’t want to get the one that says 50 percent of the Lost Pines is now unsuitable habitat for the Houston toad”

Top image: Male Houston toad (Credit: Donald Brown)

0 comments