Custom sensor ring measures extreme mixing in coastal surf zone

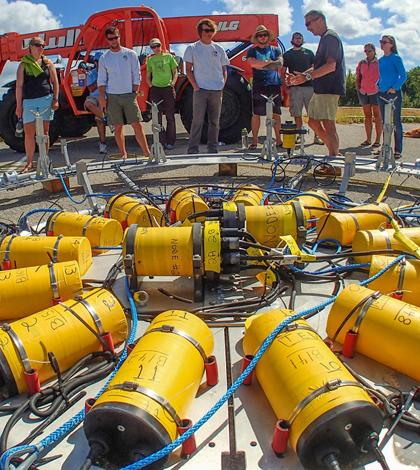

This custom-built ring of current meters measures rapid mixing in the surf zone (Credit: WHOI)

Turbulent seas in Duck, N..C.’s surf zone made installation of a custom-built ring of current meters difficult for a team of researchers, especially with a helicopter overhead lowering the ring with its propeller beating down on the already rough water.

A team from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution deployed the ring and many other sensors into the nearshore surf zone in October. They were measuring how much certain wave actions impact eddies that mix water in the surf zone.

Water in the surf zone mixes rapidly. Energy from several factors create eddies in many directions causing there to be flow in many directions. The team theorizes that some of the ocean mixing that occurs in the surf zone is caused by the edges of waves offshore in deeper water.

“We are measuring vorticity in the surf zone. The surf zone is an area of extreme mixing. If a pollutant or bacterial spill or a person is near the shoreline, it will get mixed up in the surf zone, dispersed, and carried away,” said Steve Elgar, senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “We do not yet know how fast this happens and how far stuff gets mixed.”

The current meter ring consists of 14 acoustic Doppler current profilers and two pressure sensors to measure breaking waves. It was part of a network of sensors the researchers deployed

A total of 26 additional instruments including current meters and pressure gauges also collect data across a 200-meter space around the current meter ring.

A helicopter placed the current ring in rough seas (Credit: WHOI)

Sensors collect data at frequency of 8 hertz. All of the sensors are synchronized thanks to a master clock in the ring. A data acquisition station on shore for the has a GPS synchronized clock. A camera on shore elevated 40 meters photographs the water in time series synchronized closely with wave data.

The research team, led by David Clark, assistant scientist at WHOI, and Britt Raubenheimer, associate scientist at WHOI, theorizes the edges of waves, still in the surf zone, create turbulence as they change from crash and foam to roll and sink in the deeper ocean water.

“As you go in the surf along the shoreline there will be a breaking wave crest, lots of white water and turbulence and dissipation and then suddenly a bit farther down the beach the wave is not yet breaking, so (there’s) no white water no turbulence,” said Elgar. “That change from inside the active breaker to just outside is hypothesized to generate eddies and vorticity.”

Preliminary observations show that there are compacted pockets of energy in surf zone eddies. The eddies observed varied in size and sent water in many different directions. “There appears to be a large amount of energy in quite small motions in the surf,” he said.

The ring is equipped with 14 acoustic Doppler current profilers (Credit: WHOI)

A week into the ring’s deployment, a nor’easter storm hit the area. The sensors recorded waves as high as 4.5 meters and current speeds of almost 4 knots. Elgar said the storm caused erosion, transforming the nearshore zone.

“These strong flows caused tremendous erosion and accretion, and turned the initially long straight beach into a series of crescentic sand bars that touched the shoreline on their ends, and curved offshore about 200 meters,” he said.

Change in the nearshore ocean floor caused flow in the surf zone to change. “The complicated bottom resulted in rip currents, alongshore currents feeding the rips (and) onshore flow to balance the offshore flow,” said Elgar.

The team has just finished collecting data from their current analyzing system and will now begin analyzing and processing it. A write up of their findings will follow.

Clark, Raubenheimer and Elgar designed the ring and experiment. Jay Sisson, WHOI research assistant, designed the ring’s mechanics and oversaw machine work.

Bill Boyd and Brian Woodward, engineers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography, handled the sensor systems electronics.

The project was funded by National Science Foundation and the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering.

Top image: This custom-built ring of current meters, seen here in Duck, N.C. before deployment, measures rapid mixing in the surf zone (Credit: WHOI)

0 comments