The Birds and the Bees: Understanding the Diversity of Pollinators

A Dark Paper Wasp and Western Honey Bee feeding together on goldenrod. (Credit: Emma Jones)

A Dark Paper Wasp and Western Honey Bee feeding together on goldenrod. (Credit: Emma Jones)Pollinators of all shapes and sizes are vital to ecosystems around the world. From the wide array of food people eat to the diversity of life around the planet, life would be very different without them. Pollinators are organisms that help carry pollen from one plant to another, and over 350,000 species can be found worldwide, according to The California Department of Fish and Wildlife. With the strong relationship between plants and pollinators, losing either would have detrimental impacts on ecosystems.

Over millions of years, both plants and pollinators have evolved alongside each other and formed unique adaptations that allow them to work together, expediting and enhancing the process of pollination. In order for a plant to reproduce, pollen grains from the anther must reach the stigma of another flower. Once fertilization happens, the flower can yield seeds to produce the next generation.

Pollinators around the world are responsible for much of this process. Due to simultaneous adaptations over the years, many pollinators and plants have symbiotic relationships where they both benefit from pollination.

Evolving Together

Various species, including bees, wasps, birds, butterflies, moths, flies, bats, beetles and other small mammals, are key players in pollinating the planet. Having adapted alongside the plants they pollinate, pollinators create a perfectly balanced system. To protect this balance, it is important to support both the pollinators and local flora.

Many flowering plants have evolved adaptations that attract either large numbers or specific types of pollinators in order to streamline the pollination process and become more effective. These adaptations include scent, food sources and visual traits.

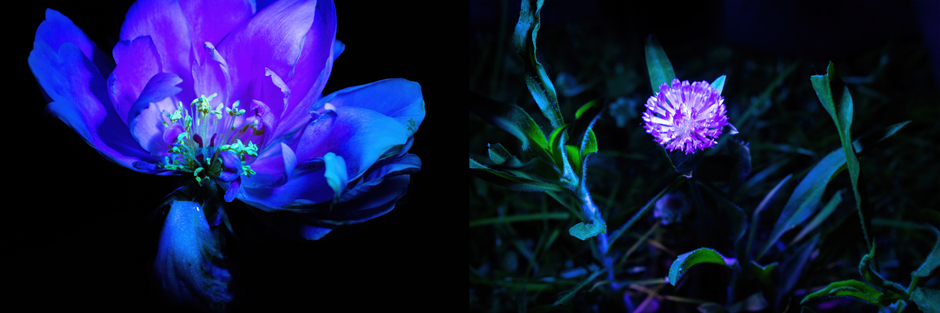

Under an ultraviolet light, people can get a glimpse of how pollinators view these flowers. With glowing colors and vibrant markings, the flower guides the pollinators to the flower and towards the most pollen and nectar-rich parts of the plant. (Credit: Emma Jones)

One example is the ultraviolet patterns found on the petals of many plants. While invisible to the human eye, bees and some other pollinators have evolved special photoreceptors to see UV light and take advantage of this adaptation, using it as a landing pad and guide to find the nectar and pollen.

A 2019 study revealed that the presence of ultraviolet-reflective color adaptations significantly increased the visitation rates of the flowers studied. When completely removed, the visitation rates of these flowers dropped and the landing behaviors of bees were altered, proving that this adaptation makes a difference in pollination success with vision-dominant pollinators.

Additionally, some plants have evolved their flower shape to cater to specific pollinators, such as the cardinal flower. Cardinal flowers attract hummingbirds specifically with their vibrant red color, sweet-tasting nectar and deep, tubular shape that only a hummingbird’s long, curved beak can reach. These complex adaptations ensure that every species receives both the food and pollination they require to survive and thrive.

Bees and Wasps

Although not the only pollinators, bees are some of the most important for the planet due to the large number and variety of flowers and agricultural crops they visit each day. According to the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, there are an estimated 20,000 species of bees worldwide, each with their own adaptations that assist with pollination.

When visiting each flower, the pollen sticks loosely to hairs on the bee. When carried dry, like in the case of solitary bees, the pollen is more likely to fall off of the bee during their journey, pollinating and cross-pollinating 95% of the flowers they land on.

Conversely, social bees make some of the pollen into a wet paste and store it in saddlebags on their hindlegs, which prevents them from losing more pollen, but can make their pollination less effective, according to Crown Bees. Many bees, however, practice flower constancy, in which many insect pollinators favor a specific plant within a trip or lifetime, a method that streamlines the pollination of specific plants rather than contributing to cross-pollination, as stated by the University of Florida.

(Left) A mining bee carrying a large clump of pollen on its hind legs. (Right) A brown-belted bumble bee feeding on a gray-headed coneflower. (Credit: Emma Jones)

Bumble bees are able to fly in colder temperatures and lower light conditions than other bees, making them more effective at pollinating, especially at places with higher altitudes and latitudes. They are often the first and last species of bees seen each year because of this adaptation.

Despite being despised by many, wasps are another type of pollinator that bring major ecological benefits to the environment through pollination and pest control. Although sometimes less effective than bees due to having less hair, wasps are important pollinators of flowers and food crops around the world.

Some wasps are considered generalist pollinators, meaning they visit a wide variety of flowering plants, while other species of wasps are considered specialist pollinators, who are more selective and only visit specific species.

As stated by the CMNS Department of Entomology, the majority of wasps can only obtain nectar from shallow flowers due to their short mouths and tongues. Some plants have evolved to be exclusively pollinated by wasps, featuring dull colors, shallow blooms and a strong scent that other pollinators don’t favor. Bees and a few species of wasps are the only pollinators who purposefully pollinate plants, while many others pollinate accidentally as they feed.

(Left) A dark paper wasp covered in pollen feeding on Goldenrod. (Right) European paper wasp. (Credit: Emma Jones)

Butterflies and Moths

A common sight in warmer months, butterflies are extremely active during the day, spending their time traveling from flower to flower and feeding on the nectar they find. Butterflies visit a wide variety of wildflowers of many different shapes and colors. They prefer plants with flat landing platforms, such as sunflowers, or clusters of flowers like goldenrod and milkweed.

Additionally, they also prefer blooms that are red, orange, yellow, white, pink or purple in color because of their ability to see both high-frequency colors and colors on the ultraviolet light spectrum. With this specialized vision, many of these colors listed glow, making them easier to find for short-sighted butterflies, according to the Australian Butterfly Sanctuary. Some studies show that butterflies may even learn which color flowers produce the nectar they prefer, says Weekand.

As stated by the USDA U.S. Forest Service, many butterflies produce flower-like scents to attract members of the opposite sex. A variety of these scents are similar to those of the flowers the species favor, which can attract more of these butterflies to pollinate, as well as help them find food.

(Left) A viceroy butterfly. (Right) A Yellow-collared Scape Moth feeding on a clover. (Credit: Emma Jones)

While the diurnal pollinators are sleeping, the pollination party doesn’t stop. With nearly 11,000 species of moths in the United States alone, these insects play a major role in the ecosystem as prey to larger creatures, as well as pollinators for many different plants.

Due to the often nocturnal lifestyle and dull coloring, moths are one of the lesser noticed pollinators, despite outnumbering butterflies 10 to 1. Recent research conducted by the University of Sussex has shown that moths are even more efficient pollinators than bees.

Some species of plants have evolved to be nocturnal with the moths who feed on them, adapting traits to help lure them in. These plants have evolved to open their blooms and smell stronger in the evenings, catering to moths’ methods of finding food. Many of these flowers are also paler in color, reflecting the moonlight and acting as a glowing, pungent beacon for moths, according to The Oregonian.

Beetles and Flies

Before bees, wasps, butterflies and other common pollinator groups existed, beetles were the primary pollinators, dating all the way back to the late Jurassic era, around 150 million years ago, according to the Xerces Society. Even with more competition today, these insects are necessary for plant reproduction, especially for ancient species of plants, such as magnolias and spicebush, who evolved alongside them.

In addition to being the oldest, beetles are also the largest group of pollinating organisms. They are very important for plant reproduction and are responsible for pollinating 88% of the 240,000 flowering plants across the planet, as stated by the University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources. Many species of beetle love to eat pollen as well, visiting species of plants that produce a surplus of pollen so that there is enough for both the beetle’s diet as well as pollination.

(Left) A trio of iris weevils feeding. (Right) A member of the Blowfly family. (Credit: Emma Jones)

Like beetles, flies are one of the most efficient accidental pollinators around, picking up and distributing pollen unintentionally as they go about their day-to-day lives. They are critical to the pollination process in both wild plants and cultivated crops, with hoverflies and blowflies being some of the biggest contributors.

Flies visit a wide variety of plants and, due to their tolerance of cooler temperatures, many flies are more active earlier in the year than bees and can provide more consistency in early spring pollination. According to Australia-based biologist, Romina Rader, while some species have their drawbacks, pollinating flies will be incredibly important for ensuring food security in the future, especially in the cultivation of greenhouse crops.

Many flies have fast life cycles and can adapt to a wide variety of habitats and conditions, can spread pollen even further than bees in search of food since they do not have families to provide for, and can tolerate colder temperatures and harsher weather, braving conditions that bees and other pollinators would typically avoid.

Birds and Bats

Another unique category of pollination is the pollination of flowers by birds. According to the U.S. Forest Service, there are 2,000 species of birds around the world that feed on nectar as well as the insects and arachnids associated with nectar-producing flowers. In the U.S., hummingbirds are essential in the pollination of native wildflowers.

With a heart rate of up to 1,200 beats per minute and wings that flap 70 beats per second, hummingbirds require a large amount of sustenance to survive and must eat several times their weight in nectar each day. Additionally, they supplement their diet with insects for added protein. As they feed, reaching deep into the flowers with their slender bills, their faces become dusted in pollen, spreading pollen to more flowers.

According to the National Park Service, hummingbirds who breed in North America spend the winter in Mexico, following various migration corridors in their travels depending on the species. These pollinators time their migration with the flowers they feed on, ensuring that they will be in bloom when they arrive at their destination. Unfortunately, due to habitat loss, a changing climate and changes to the population and distribution of nectar-producing plants, this synchronization between the hummingbirds and plants may be altered, putting both at risk.

(Left) A ruby-throated hummingbird using its long, slender beak to feed on a royal catchfly. (Right) A brown bat clinging to the wall of a barn at the Fondriest Center for Environmental Studies. (Credit: Emma Jones and Steve Fondriest)

The pollination of plants by bats is another important side of pollination. Like moths, bats are nocturnal pollinators, supporting many evening-blooming flowers. According to the Bat Conservation Trust, over 500 species of plants and fruits rely on bats for pollination, while bats rely on their flowers and produce to survive.

One of the major contributors to the bats’ decline is human disturbance in their habitats and food sources, with one example being the farming habits of agave plants, which are used to make tequila. During production, farmers often harvest before the plant blooms. This limits the bats’ food sources as well as the pollination of the plant, which already has very little genetic diversity. Disease, habitat destruction and lack of food are major risks for bats and can have a domino effect if it continues, lowering the populations of a variety of plants and animals.

Protecting Pollinators

With many threats impacting this delicate process, the survival and quality of life of many animals, plants and people around the world hangs in the balance. According to Britannica, the diversity and availability of fresh food will diminish, leading to declines in human nutrition. Many crops would not be cost-effective to grow and would lead to a drop in those plants’ numbers. While hand pollination is possible for most crops, it is very labor-intensive and expensive. In addition to losing crops, the planet would lose many wild species in all tiers of the food chain.

The good news is that it is not too late. There is a lot that people can do to help protect these organisms. Among the most important initiatives are planting native plants for pollinators, educating others and eliminating or reducing the amount of pesticides and herbicides used.

Offering a place for pollinators to get a safe drink, such as a shallow water dish filled with stones and sticks, is another great way to support pollinators. Leaving dead leaves and plant material in the fall can give a variety of pollinators a home to support them through the winter season. During nesting season, according to the National Park Service, potential nesting sites can include trees, shrubs, brush piles, bare ground and bee boxes. When planning a pollinator garden, it is always best to do research and learn about the native species and what they require to thrive.

(Left) An assortment of native wildflowers planted at the Fondriest Center for Environmental Studies. (Right) A Monarch Butterfly feeding on Swamp Milkweed, a native Ohio species of the Monarch’s host plant. (Credit: Emma Jones)

At the Fondriest Field Station, environmental scientists and naturalists have been working to improve conditions for pollinators in a variety of ways. The biggest initiative has been the planting of native flowers and pollinator gardens. These gardens feature a variety of native wildflowers and plants that local pollinators prefer.

Best practice is to plant for continuous bloom throughout the growing season, which means there will always be something in bloom from spring to fall for pollinators to feed on. In the early spring, people can help by not removing dandelions and other native plant life, even if they are considered weeds, as these are often a pollinator’s first food sources of the year.

Downed tree limbs, logs and shrubs have been left in the treelines for pollinators to nest in as well. Additionally, plans for pollinator structures, such as bat houses and bee condos, are also underway. If built properly, these structures can provide a safe place for a variety of bats, solitary bees and other pollinators to nest in.

Even small efforts by individuals can help pollinators, especially on a local scale. With more people’s help, pollinator populations can thrive once again.

0 comments