Cornell University Biological Field Station at Shackelton Point: Monitoring New York’s Largest Interior Lake for Sixty Years

Intern Omisha water sampling in Oneida Lake. (Photo credit: Michelle Holeck)

Intern Omisha water sampling in Oneida Lake. (Photo credit: Michelle Holeck)Lars Rudstam, Professor of Aquatic Science at Cornell and Director of the Cornell University Biological Field Station at Shackelton Point, says that he has long held an interest in lakes in general, so naturally the Great Lakes, the largest freshwater lake system in the world, have held a fascination for him for many years. He also works on Oneida Lake, the largest lake wholly inside New York. Oneida Lake waters, traveling from the Lake to the Oneida River, then to the Oswego River, ultimately flow into Lake Ontario. “In addition to lakes in general and the Great Lakes, I have been especially interested in the impressive data series that has been collected for Oneida Lake,” Rudstam notes. “Oneida Lake data is some of the best data that has been collected for understanding species impacts and climate change effects.”

The Oneida Lake ecosystem has been the subject of extensive data gathering, some of it going back 60 years. Data has been collected on everything from water quality and nutrients to fish and the birds that eat them. “We are interested in the whole lake,” says Rudstam. “We collect data on many aspects.”

Lake nutrient samples are collected weekly at Oneida Lake. A Hydrolab Datasonde unit is used to collect temperature, oxygen and pH information. Fluorometers are also used to collect information on algae. For those, German Moldaenke fluoroprobes are used. HOBO temperature loggers are also utilized in the field. The water quality data has been taken for 50 years.

Intern Ria collecting water samples in Oneida Lake. (Photo credit: Michelle Holeck)

Data on fish have also been taken for 50 years. Data includes fish abundance, diet and growth rates. Parasites on fish are also monitored. “We see parasitic copepods showing up in fish gills,” Rudstam mentions. “Invasive species are constantly coming into the system.”

Some of the common fish include walleye, yellow perch, smallmouth bass and largemouth bass. “We are also seeing round goby, which eats the eggs of some of the other fish. On the other hand, some of those other fish prey on the goby, and the goby does eat zebra mussels, an invasive species we’ve had for many years,” Rudstam mentions.

A large number of people fish on the public Lake, as many of its fish are tasty game fish, such as the walleye. “The current limit is three walleye a day,” notes Rudstam. “The walleye population has increased in the past decade. About 50,000 walleye are harvested each year from the lake. We’ve also been seeing some increase in cormorants, which are fish-eating birds.” Sheepshead and carp also live in the Lake but are not typically taken as game.

While no plants are specifically being threatened in the Oneida Lake system, European milfoil and starry stonewort, a macroalga, are considered to be invasive and have been affecting the ecosystem.

Intern Omisha water sampling in Erie Canal. (Photo credit: Michelle Holeck)

Lake Oneida data shows differences in the Lake over time that indicate climate change. “We have seen an increase in temperature of about two degrees Celsius since the 1970s,” Rudstam indicates. “We also have less ice cover duration in the Lake than we used to, about a month less than it used to be.”

Oneida Lake’s behavior is partly influenced by the fact that it is a shallow lake that doesn’t stratify like the deeper lakes in the Great Lakes system. It is only 16 meters deep at most, averaging about only 7 meters deep. “Lake St. Clair is similar, it is shallow also and doesn’t stratify,” says Rudstam.

In Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Ontario and Erie, researchers at the Field Station at Shackelton Point have been working with the EPA to monitor zooplankton, chlorophyll and bottom animals such as worms, insects, plants and mussels. Sampling is conducted in April and August, and sometimes at other times of the year as well. The EPA research vessel “The Lake Guardian” is used for these studies. This research is in collaboration with Buffalo State and employs graduate students and several technicians to gather and process data. These data are used to look for trends over time and to create indices for the status of lake ecosystems.

“Blue-green algae is still a problem in the Great Lakes system, as it has been for many years,” says Rudstam. “But we have seen some progress with persistent contaminants PCB and DDT. They have been slowly going down. The numbers have definitely become lower since the 1970s.”

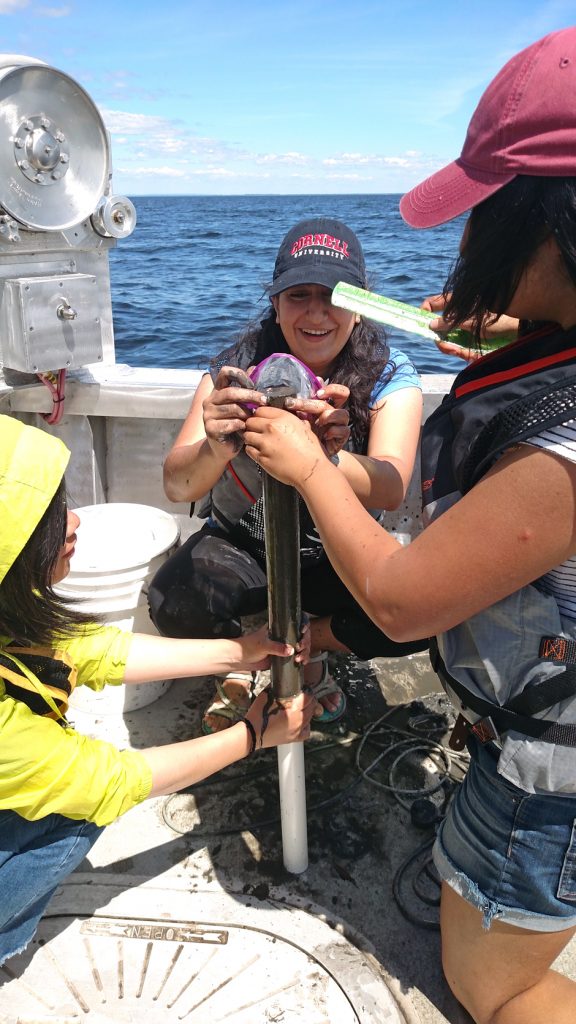

Visiting scientist Carol along with interns Omisha and Ria collecting sediment samples in Oneida Lake. (Photo credit: Michelle Holeck)

While he has had a great familiarity with Lake Oneida and the Great Lakes ecosystems over the years, Rudstam has still been surprised by some observations that have been made. “I’ve been surprised by some effects of zebra mussels, which invaded the lakes many years ago. The mussels have cleared the water, and that has had all sorts of effects for the ecosystem. They are still spreading across North America. In Oneida Lake, they have simply become part of the ecosystem. Instead of trying to eradicate them, I think people have come to realize that we will just have to learn to live with them,” he says.

The Oneida Lake data has made it possible to understand many aspects of the lake ecosystem better, and the work on the Great Lakes is used to determine what the future might hold for the largest freshwater system in the world.

“We could not observe the changes we see without environmental monitoring and good data sets,” Rudstam emphasizes. “They are critical to our understanding.”

More on the Cornell University Biological Field Station at Shackelton Point, a member of the Organization of Biological Field Stations (OBFS) here.

Philip Ewanicki

April 15, 2020 at 10:40 AM

I worked at Shackleton Point for Dr. John Forney the summer of 1961 under the impression that field station had been in existence for more than a year?

Katelyn Kubasky

June 17, 2020 at 3:16 PM

The article states that there are data sets that go back 60 years, this does not mean that the station itself has only been around 60 years.