Once Upon An Oyster: Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory Helps Protect New Jersey’s Century Old Shellfish Industry

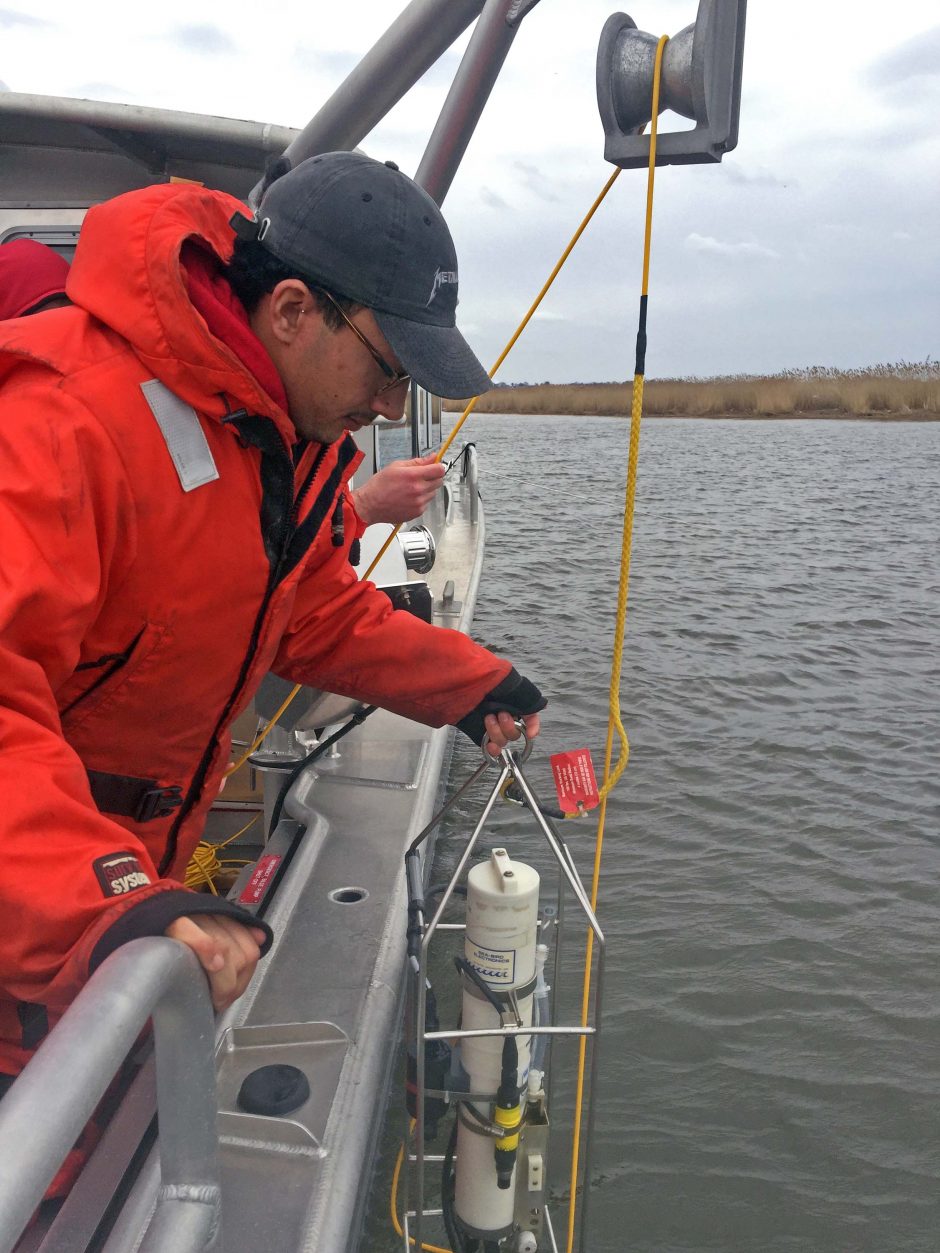

A Rutgers undergraduate student deploys a SeaBird CTD (Conductivity-Temperature-Depth) data sonde in the Raritan River to collect temperature and salinity profiles to locate and describe the salt wedge create by tidal exchanges in the estuary. (Credit: David Bushek)

Dave Bushek, Director of the Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory and Professor of Marine and Coastal Science at Rutgers, has spent 15 years at the Shellfish Lab. In that time, there has been a lot to be proud of. “We’re the third most productive oyster research lab in the world,” he says. “Our geneticist is also the second most productive in the world.” All of that research is built on a foundation of knowledge about shellfish, an industry that has been going strong in New Jersey for over a hundred years.

“The shellfish industry started with oysters,” Bushek explains. “Now it includes clams, scallops, squid, hard clams and also aquaculture work.”

A member of the Organization of Biological Field Stations (OBFS), the Haskin Shellfish Research Lab performs many studies that benefit the New Jersey shellfish industry. “We do stock assessments of fisheries to improve and ensure their sustainability,” Bushek says. “We also look at how climate change impacts ocean acidification and other environmental changes that will affect shellfish. The largest focus of my lab is on disease. We are especially interested in oyster diseases.”

Part of being one of the world’s most productive labs involves collecting a lot of data. “We gather traditional data, such as fisheries harvest or directed sampling of shellfish from research vessels. But we also use newer technologies such as using data sondes to gather water quality information like oxygen data. We work with the Coastal Ocean Observation Laboratory to gather remote sensing data and we’ve recently used video surveys in interesting ways, such as to monitor scallops or demonstrate how easily horseshoe crabs traverse oyster farms on their way to spawning beaches,” Bushek mentions.

Dr. Joshua Moody, Senior Restoration Coordinator for the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, uses a Trimble RTK-GPS (Real Time Kinematic – Global Positioning System) to accurately map the location and tidal elevation of an oyster rack as part of a study examining the effects of tidal exposure on vibrio bacteria growth in farmed oysters. (Credit: David Bushek)

In terms of the data sondes, Bushek says the Haskin Lab uses a fleet of YSI EXO2 sondes to monitor water quality changes in collaboration with Versar Inc. “We have nine deployed. The sensors monitor water quality changes. We gather data on dissolved oxygen, water level, temperature, salinity, turbidity and pH.”

But the heart and soul of Haskin Lab remains oysters. “We monitor the oyster population in Delaware Bay for recruitment, growth, disease and survival to help the state and the industry sustainably manage the resource.”

There are two main oyster diseases that Bushek and his team monitor. One is caused by the protozoan Haplosporidium nelsoni and has been around since 1957. This disease is called MSX, or Multinucleated sphere X, referring to the many nuclei of the protozoan. “Oysters have developed quite a bit of resistance to it,” says Bushek. The other disease, the one that is actually striking oysters harder, is called Dermo, and it has been around since about 1990. “Neither disease is harmful to humans,” Bushek emphasizes. Outbreaks of Dermo have become worse as climate change has warmed waters, as Dermo is a warm water pathogen. “Some oyster deaths are natural. I would say about 5-10 percent mortality is natural,” says Bushek. “But because of Dermo, it’s now more like 20-30 percent mortality.”

An Onset HOBO Salt Water Conductivity/Salinity Data Logger (U24-002-C) is fouled by bryozoans after one month of deployment in Delaware Bay. (Credit: David Bushek)

While a 20-30 percent mortality for oysters sounds very serious, Bushek says that the environment itself can push back on Dermo. “We’ve seen that if there’s low salinity in the Bay, the Dermo retreats,” says Bushek, “and we are seeing that now with the persistent wet weather since July. On the other hand, if we get a drought, Dermo becomes worse.”

MSX and Dermo aside, oyster management at Haskin continues apace. “We work with the industry and the state to manage oysters by manipulating where they are in the Bay to try to optimize conditions for them,” Bushek explains.

Oyster and clam shells are recovered from shell processing businesses. The shells are then placed in areas where oyster larvae are likely to attach to them and thrive. They can then be transplanted to areas more favorable for them to grow into adult oysters. “We don’t move the whole population,” says Bushek. “We’re just trying to increase survival and growth by moving part of the population.” The shellfish industry uses oyster dredges to pick just the top bed of oysters to move.

In terms of monitoring the oysters, a rigorous sampling program is used to estimate the population. For these quantitative surveys, about 150 samples are taken. To get oyster estimates at the bottom of the Bay, an oyster fishing boat uses a dredge that is calibrated prior to the maneuver. “We used to send down divers with quadrats, and they would collect replicate samples from square meter quadrats of the bottom to validate what the dredge collects. Now we use patent tongs that grab a square meter of the bottom for analysis on deck,” Bushek mentions.

Dr. Daphne Munroe of the Haskin Shellfish Research lab records sonar imagery from a DIDSON 300m to study how easily horseshoe crabs traverse oyster farm gear on their way to spawning beaches. (Credit: David Bushek)

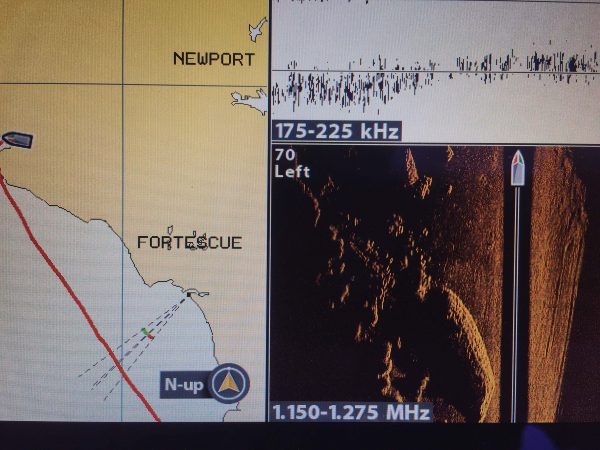

While video has been used by the Haskin Lab, in most areas the water is too turbid to use video. “In those areas, we are experimenting with sonar,” says Bushek. “Another neat thing we do is monitoring plankton with a FlowCam, not everyone is doing that. It allows us to quickly look at many different plankton parameters.”

The work done by the Haskin Lab in Delaware Bay has resulted in one of the only wild shell-fisheries that are considered sustainable. “We have done a lot of work to make ourselves worthy of that distinction. But we also rely on our collaborations with academic, industry and regulatory partners. We not only get support from them, but we also give back, in terms of data that we provide their management, which helps them make the best decisions for their organizations,” Bushek adds. “We’re a small facility, with just three faculty. But we have a rich history that goes back a century. Our original Director began work on oysters in 1888.”

Sidescan sonar imagery (lower right) is combined with navigation data and benthic sonar to monitor the performance of a living shoreline created with oyster castles — note the reef like structure in the bottom center of the image. (Credit: David Bushek)

As for himself, Bushek has found that the rich history of the Haskin Lab and his own history have become intertwined, perhaps by fate.

“I became interested in shellfish pathology because it was always clear to me how important it was to protect the shellfish here. They provide so much for so many,” Bushek enthuses. “I was initially interested in shrimp aquaculture. But the opportunity that presented itself was in marine ecology, where I began studying oysters and barnacles. Later, because of my work with oysters, I was offered a chance to do a doctorate in shellfish.” The rest is history, which Bushek and his colleagues continue to make each year with their distinguished research.

For more information about the Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory at Rutgers University visit https://hsrl.rutgers.edu/.

Top image: A Rutgers undergraduate student deploys a SeaBird CTD (Conductivity-Temperature-Depth) data sonde in the Raritan River to collect temperature and salinity profiles to locate and describe the salt wedge create by tidal exchanges in the estuary. (Credit: David Bushek)

0 comments