Pennsylvania’s Lacawac Sanctuary Offers Rare Pristine Glacial Lake to Researchers

The red spotted newt or "eft", the terrestrial juvenile stage shown here, are very common at Lacawac. (Credit: Mikayla Kocan, 2018)

The red spotted newt or "eft", the terrestrial juvenile stage shown here, are very common at Lacawac. (Credit: Mikayla Kocan, 2018)Lacawac Sanctuary’s claim to fame is that it possesses the southernmost unpolluted glacial lake in the U.S. Pristine lakes are rare today, and Lake Lacawac is an invaluable resource for conservationists and research scientists. Lacawac Sanctuary was also named a National Natural Landmark in 1968. The name of Lake Lacawac, interestingly, comes from the Lenape Indian term for fork. Consisting of 510 acres, the Sanctuary includes mature second-growth forests, two ponds, several wetlands and a mile of Lake Wallenpaupack shoreline. There is also a suite of buildings that date back to the turn of the 20th century. Some of the buildings, such as the Ice House, the Lodge and the Carriage House are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Lake Lacawac is so untouched and so precious, only researchers are allowed to use watercraft on the lake. Swimming and fishing are also not allowed. “Not only do we need to restrict the lake to researchers, if they want to use their own watercraft they need to wash it with a four percent bleach solution before they can go out on the lake,” says Beth Norman, Director of Science and Research at Lacawac Sanctuary. “Otherwise, the risk of contamination with invasive species is just too high.”

Lake Lacawac. (Photo credit: Mikayla Kocan, 2018)

Norman is a relatively new addition to Lacawac Sanctuary, arriving in February 2018. Her doctorate was completed at Virginia Tech in the area of Biological Sciences, specifically Aquatic Ecology. She did postdoctoral work at Trent University in Ontario and the Michigan State University.

“Lacawac Sanctuary wanted someone with the right research background for this position, and I wanted to work at a place where I could not only do my own research but also interact with researchers all over the world. I also like that we’re not just a field station here, but also an education center. The Director position here turned out to be a great fit for me,” says Norman.

All kinds of students visit Lake Lacawac, from preschool age to high school to undergraduates. Undergraduate and doctoral students, usually about 5-7 students, work there in the summer on about 15 projects. Lacawac Sanctuary educational facilities are designed to bring research science and scientific methodology out into the open, so students can see how the research process actually works. “People like to see scientists doing actual science,” Norman explains. “That’s one of the great things we offer here.”

Norman’s current research involves taking a look at nitrogen cycling at lakes in the region, and how nutrients move through the ecosystem.

“I would say our big focus here is limnology,” says Norman. “We have the southernmost unpolluted glacial lake in the U.S. because, in the early 1900s, this area was purchased by a family for their second home. As a result, the entire watershed here was not developed.” This created a boon for researchers. “We can study the ecological area here that has been untouched by people. It’s a rare find. We can, therefore, isolate the effects of climate change, look at native, pristine plankton populations and gather remote sensing data with buoys,” Norman adds.

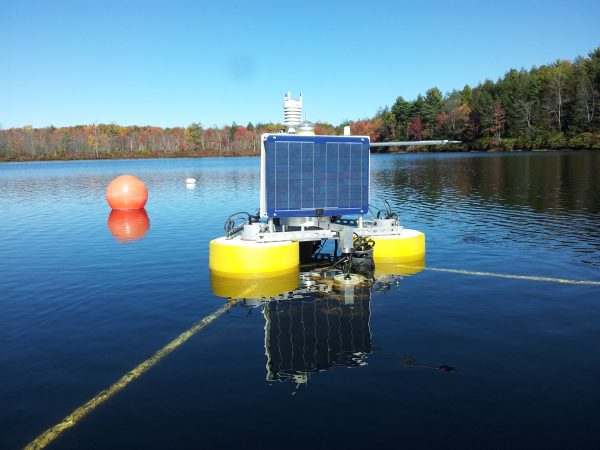

Lake Lacawac has two main research buoys: the RAFT and the ARTHUR. The RAFT has been on the lake since 1992, and it’s on the lake year round. During the winter, it is docked on the lake, but still gathering data. It takes data every 15 minutes, year round. There is also a weather station on a platform on top of the RAFT, which transmits information about lake weather. Lehigh University’s Bruce Hargreaves did much of the pivotal work outfitting the RAFT.

Sitting on Lake Lacawac year-round is the research platform, RAFT. (Credit: courtesy of Lacawac Sanctuary)

The ARTHUR buoy, named for Arthur Watres (founder of the Lacawac Sanctuary), also sports a meaningful acronym. ARTHUR is also: Aquatic Resource for High Frequency Underwater Resource. It was launched on the lake in 2011. The ARTHUR goes in and out of the lake each summer. It has recently had additional sensors added. What makes the ARTHUR unique is that it has a winch with a buoy platform that can go up and down the entire water column. Every six hours it does a complete profile from top to bottom to top again. The ARTHUR is run by Miami University in Oxford, with Craig Williamson acting as the POC for the effort.

Data gathered by the buoys include temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, conductivity and chlorophyll-a. The lake also has dissolved oxygen sensors every meter.

A weather station is also located on land, and it gives terrestrial wind speed. YSI handheld meters, Pro Plus units, are used for work on Lake Lacawac and on other area water bodies. These are used to measure pH, conductivity and temperature. “The information we gather is disseminated widely, as we are also a member of the Global Lakes Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON),” says Norman. “The data are used in many ways, including helping area leaders make management decisions.”

“Something we keep an eye on in the lake is algal concentrations,” Norman mentions. “We don’t currently see HAB like many other bodies of water have in this area since this lake is pristine and people aren’t using it for transport. Even so, we are always concerned about the possibility of invasive species.” Each pond, for example, has unique equipment to prevent contamination.

Pictured here is the ARTHUR data buoy platform. (Credit: courtesy of Lacawac Sanctuary)

“The pristine lake conditions make it possible for us to separate local vs. global drivers in changes we see,” Norman explains. “It’s important to keep it pristine, or we won’t be able to make those very important distinctions in our research.”

In addition to the extensive Lake Lacawac studies, there is also a deer browsing study that has been ongoing for 20 years. “There are two permanent study areas, one with deer and one without for comparison. We are looking at the impact of deer browsing on forest regeneration,” Norman mentions. “Deer are native to this area, but they were almost completely wiped out by the early 1900s. Later, deer were imported to this area for hunting. Deer you see here today are likely descendants of those imported deer.”

Some invasive species Norman and others keep watch for include milfoil plants, tough macrophytes that can be re-hydrated after drying up; Asian clams; and zebra mussels.

Some native fish species in Lake Lacawac are perch, sunfish, smallmouth bass and pumpkinseed. Red-spotted salamanders can be found in the area, as well as bald eagles (though the bald eagles aren’t nesting).

“We’ve lost the American chestnuts we used to have in the 1900s,” says Norman. “It’s actually easier for us to protect the lake than the forest.”

The lake is a seepage lake. One side is sandy, and the other side is a bog. “We’re trying to restore habitat for the Golden-winged Warbler,” adds Norman. “They like scrub habitat, so we are selectively logging the canopy to try to help them.”

Graduate student Rachel Pilla from Miami University of Ohio deploying the dissolved oxygen sensor string. (Credit: courtesy of Lacawac Sanctuary)

Some of the 20th-century buildings on the property are also a focus for preservation. “They are some of the first examples of the Adirondack style of architecture in the Pocono region,” Norman indicates.

In terms of future plans, Norman says Lacawac Sanctuary plans on doing a better job curating the data they already have. “We would like to get it better organized and archived,” she says.

In addition to all the other special things about Lake Lacawac, Norman mentions it’s also a really good place to deploy prototypes. “There are so few people here, and the only ones who are here on the lake are researchers. That means if you launch a prototype here, no one will mess with it,” Norman says.

Lacawac Sanctuary is involved in long term biological research funded by the NSF. They have collaborations with Miami University in Oxford and RPI in New York. “We’re all committed to long term data collection,” Norman says.

Working at Lacawac Sanctuary has been rewarding for Norman. “It’s really gratifying to see students invested in their own research and in making Lacawac Sanctuary work. It’s a communal research effort,” she enthuses. “I also love living on site. Where else can I wake up and see a black bear pressing its nose on my window?”

0 comments