San Francisco Bay’s Nutrient Phenomena

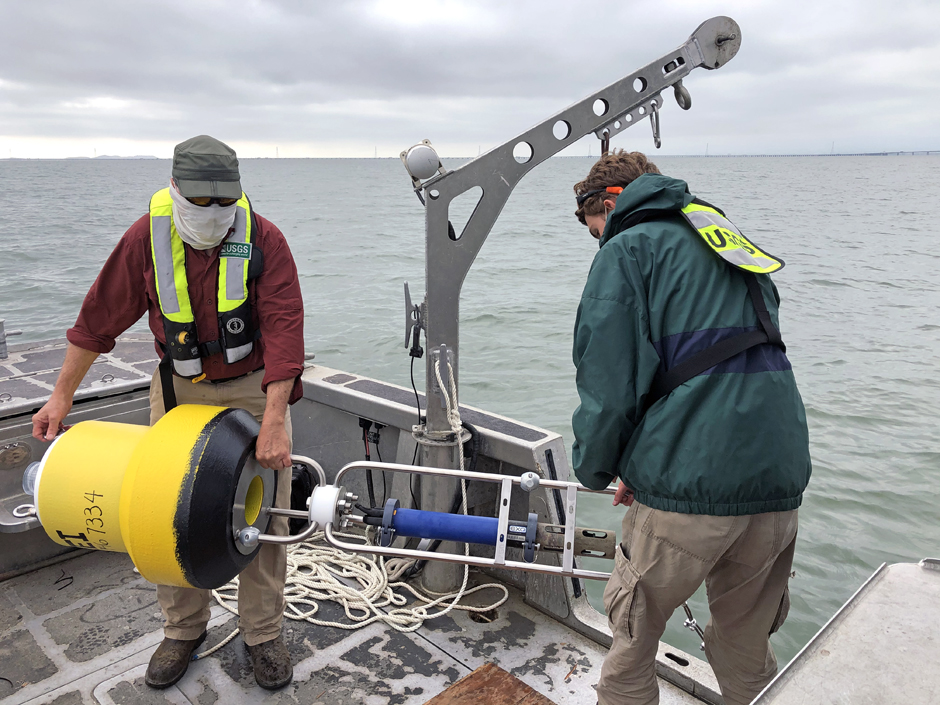

This lightweight buoy is equipped with an instrument cage, anti-rotation collar for stability and sacrificial zinc anode for protection against corrosion while deployed. (Credit: SFEI)

This lightweight buoy is equipped with an instrument cage, anti-rotation collar for stability and sacrificial zinc anode for protection against corrosion while deployed. (Credit: SFEI)From the gold rushes to the birth of Silicon Valley, the San Francisco Bay Area is known for welcoming swaths of people looking for a new frontier of culture and natural beauty. It has had a front-row seat to some of America’s most rapid industrialization and population growth for the past 200 years and is now home to over seven million people. Tourism booms as people from all around the world come to see the iconic Golden Gate Bridge and the expansive bay that lies beneath. But the bay is not just for looks. It plays an essential role in supporting modern California living–and we are not just talking about surfing.

Water from every toilet flush, shower and load of laundry is treated and pumped back into the bay. San Francisco’s wastewater management processes have kept cities going and scientists busy for quite some time. The San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) researchers are committed to monitoring contamination levels in the bay and studying the associated ecological impacts. Derek Roberts, PhD, is an environmental scientist with SFEI’s Clean Water Program, specifically the Nutrient Management Strategy (NMS), one of the nation’s leading water quality science programs aimed at protecting aquatic resources.

Concern arose for the Estuary in the late ‘80s, and SFEI was born in 1993. More recently, environmental regulating authorities proposed that publicly owned treatment works either decrease their nutrient load or fund studies to determine the effects. Given the option, the facilities chose science over reform. This was a catalyst for the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board to instate the Nutrient Management Strategy as their response.

The NMS project is a collaboration with the USGS California Water Science Center Biogeochemistry Group that spans a myriad of studies like water quality monitoring, targeted field investigations, and numerical modeling. The goal of this adaptable, ongoing study is to allow data to shape suggested practice standards. While libraries of data exist for parts of San Francisco Bay, there are lesser-studied areas that may hold the key to unlocking the nutrient mystery and identifying natural protective processes that have the potential to fail.

The buoys just before deployment showcase the NexSens custom-built cage that secures a Sea-Bird Scientific SUNA V2 UV nitrate sensor. (Credit: SFEI)

Nutrient Phenomenon

It is no secret that San Francisco Bay is full of nutrients. But many find it shocking that harmful algal blooms (HABs) have historically been a rare occurrence. While the potential for such issues to persist has long been present, other factors like turbidity, tides and natural processes seem to have inhibited growth in the past.

Roberts explained that “San Francisco Bay has some of the highest nutrient concentrations of any major estuary in the world but it rarely exhibits the symptoms that come with nutrient loading, like harmful algal blooms (HABs) and low dissolved oxygen…So the bay has this dynamic, complex system that has generally been resilient to pollution, but in recent years, has been showing some weaknesses.”

The weaknesses Roberts alluded to are concerning. The phenomena of SF Bay’s resilience to eutrophication may be dwindling, potentially increasing the risk for harmful algal blooms (HABS) and hypoxic conditions. Significant increases in phytoplankton biomass since the ‘90s, an unprecedented autumn phytoplankton bloom in ‘99, steadily decreasing DO levels and a red tide event in ‘04 are all red flags of a system that can’t quite keep up. Share on X

The health of the bay is of utmost importance, and surprisingly, is naturally predisposed to a robust resilience against pollution. In spite of high nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations from wastewater, HABs don’t seem to manifest to the extent science would expect. This phenomenon is largely due to heavy tidal flushing, multitudes of filter-feeding clams, and the turbid water conditions characteristic of San Francisco Bay.

While tides are strong, nutrient levels remain high. Clams filter feed the algae and high turbidity blocks sunlight from allowing algae to germinate, subsequently avoiding triggers that cause low dissolved oxygen. In spite of these systems that have sustained the bay for so long, standard practices may have to change in order to maintain the health of the bay.

“From historical data we believe that at any given time there are enough nutrients in the bay for algae to thrive,” Roberts noted, “But there isn’t enough light in the channel for them to manifest in absent stratified conditions. However, preliminary data on the shoals may be suggesting otherwise.”

Team members deployed the buoys on August 12 with full intent to return a month later for servicing and data collection; however, smoky conditions from the outbreak of fires delayed their return. (Credit: SFEI)

Topography

San Francisco Bay has a deep channel running through its center that has been closely monitored for years. The most well known area is beneath the Golden Gate Bridge that spans the deepest part of this channel, a profound 372 feet from ocean surface to floor. However, from an aerial view, wide shallow shoals on either side of the channel dominate the bay itself. Not nearly as much research has been done on the shoals and Roberts is hopeful for enlightening data that could fill in the gaps of the nutrient phenomena.

“[In the channel] Even when there is a relatively large algal bloom, we don’t see nutrient levels dropping to where we would consider the system nutrient limited. However, new findings on the shoals have shown that the system may become nutrient limited but we need high frequency data to understand if and when that happens. And It’s on those shallow shoals that some of the most complex biogeochemical processes happen–nutrient cycling, algae growth, etc.”

In mid-August of this year, Roberts’ team launched a new shoal monitoring program. Roberts suspects data may show algal blooms on the shoals that become nutrient limited. He explained that if the data supports that nutrients are the limiting factor in shallow regions, then the team will be able to better gage sensitivity to nutrient levels. He is interested to know whether or not they need to decrease, and if so, to what degree.

Approach

Two new NexSens CB-50 data buoys that now float in the shoals are equipped with a YSI EXO2 multiparameter sonde and appropriate sensors complete with a wiper for anti-fouling. The buoys are also fitted with a SUNA V2 nitrate sensor by Sea-Bird Scientific, which is suspended beneath the buoy platform inside a custom cage from NexSens Technology.

“The goal of this project is to collect a combination of water quality data, conductivity, temperature, depth, algae chlorophyll and dissolved organic matter data along with nitrate concentrations on the shoals so we can understand the interplay between shoal and channel processes and gain a fuller picture of what’s going on in the bay.”

The short term goal of the Nutrient Management Strategy is to come up with nutrient concentration recommendations for regulators. Long term goals include continuing baseline monitoring to flag symptoms of nutrient impacts and to build up a database on the mysterious San Francisco Bay shoals.

With potential California wastewater policy revisions looming in the future and gaps in nutrient data, the relatively new Nutrient Management Strategy is eager to play a significant role in the decision making processes as a leading research baron.

NAA

October 16, 2020 at 2:03 PM

Decades of research, testing and monitoring alone have not fixed any of these water quality problems.

Nutrient runoff needs to be reduced and commercial algae bloom and HAB remediation needs to be deployed to fix these devastating problems.