Monitoring Mariculture in the Gulf of Alaska

The mariculture industry in the Gulf of Alaska has been steadily growing in recent years, guided by ongoing research to help refine farm location and cultivation practices. A subset of aquaculture, mariculture focuses on rearing organisms in the open ocean.

In Alaska, finfish farming is illegal, so most farms cultivate kelp, oysters, or a combination of the two. These small, locally operated farms started popping up in the Gulf of Alaska in the early 1990s, when shellfish farming first became legal. Kelp farming did not begin to catch on in the state until 2016.

Many of the coastal areas that have grown interested in mariculture are historically commercial fishing communities. However, in the past couple of decades, commercial fish stocks and the market around them have become less stable.

One event leading to the instability of the fishing industry in the central Gulf of Alaska was the 1989 oil spill of the Exxon Valdez. This event devastated the Gulf’s fisheries, ecosystems, and the local economy.

In 2023, Mariculture Research and Restoration Consortium, or MarRecon, for short, was started with the goal of studying the developing mariculture industry in the Gulf of Alaska, specifically in areas impacted by the oil spill. The project looks at mariculture through the lens of ecological and economic restoration to these areas.

MarRecon partner farm, Spinnaker Sea Farms, on a snowy spring day. This farm is located in Kachemak Bay near Homer, Alaska. (Credit: Sierra Greene / University of Alaska Fairbanks)

How Mariculture is Monitored

Sierra Greene is one of many researchers working to study and improve mariculture operations in the Gulf. MarRecon researchers study various aspects of mariculture, from its impact on fish and bird communities to crop cultivation and the economics of it. Greene’s role is to study the oceanographic principles surrounding farms to help explain growth.

The program partnered with nine aquatic farms across the state in the Kodiak Archipelago, Prince William Sound, and Kachemak Bay. With the goal of monitoring water quality and correlating data to growth, Greene and her colleagues deployed “production arrays” on each farm.

These arrays are made up of lines and buoys that house oceanographic sensors, as well as grow kelp and oysters. The oceanographic monitoring sensors measure the temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and chlorophyll of each site.

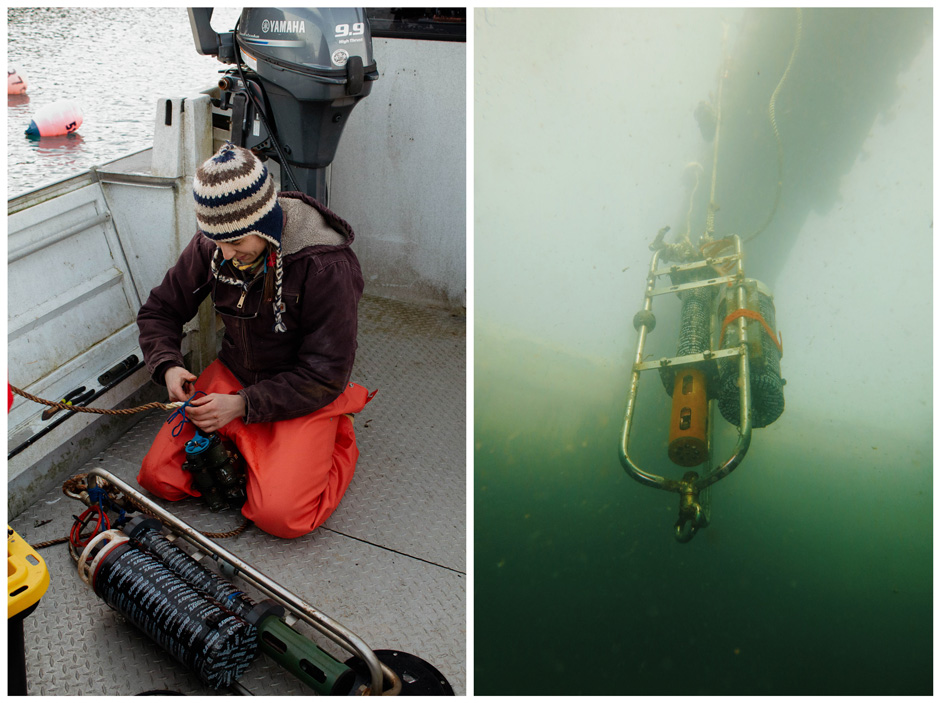

(Left) Researcher, Sierra Greene, servicing the mooring located on the Native Village of Eyak research kelp farm in Prince William Sound. (Credit: Jessica Whitney / Alaska Sea Grant). (Right) Production array oceanographic mooring, including the YSI EXO2 and its NexSens battery pack, hanging from Bootleggers Cove Oyster Farm in Kachemak Bay. (credit: Jessica Whitney / Alaska Sea Grant).

Sensor instrumentation at each site varies, though most are YSI EXO2 or EXO3 sondes deployed at about three to four meters down year-round.

Greene maintains the network of arrays, visiting each site every couple of months to calibrate sensors and offload their data. “Then I work up all of that data to try and look at some regional trends and differences between each site,” states Greene.

In addition to the sondes managed by Greene, the farmers conduct their own water quality monitoring as partners of the project. Once a month, the farmers collect CTD casts to capture stratification and conditions throughout the water column. They also collect and filter water for inorganic nutrient samples.

Greene explains, “We have a lot of freshwater influence that’s pretty different between each site. So, we’re trying to see what the different bodies of water look like within each region because of this.”

All of the collected data is used to generate reports for the farmers and also models to predict kelp and oyster growth at each site using all of the collected parameters. This data is then shared publicly through the Alaska Ocean Observing System (AOOS) network.

Kelp farmer, Nick Mangini, holds up giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) from a wild kelp bed near his farm in Kodiak, Alaska. (Credit: Jessica Whitney / Alaska Sea Grant).

Monitoring Challenges in Alaskan Mariculture Operations

When designing monitoring solutions for this project, organizers had to consider the unique environmental demands and data needs.

First, each site is remote and only accessible by boat, so instrumentation must be durable and capable of enduring a range of conditions. Some sites are situated in protected bays that are sheltered from storms but exposed to glacial runoff that can form ice sheets in the winter, while others are more exposed to larger waves and currents, but not likely to have the freshwater influence.

Second, mariculture in the Gulf is different from common aquaculture ponds that operate in a much smaller, more controlled area—these kelp and oyster farms are operated in open water, supported only by lines, anchors, and buoys.

Building off this is the size of the Gulf of Alaska, which has made monitoring difficult, leading to limited knowledge of the coastal nearshore areas of the Gulf.

Greene explains, “The coastline of the Gulf of Alaska is just massive and each area is very different. […] So, we’re trying to collect more data on that in general, and then see which areas are best for growing kelp and which areas are best for growing oysters, and try to make similarities between different sites so that when new farmers want to get involved, they can have a better idea of where to look.”

She continues, “For instance, would an area that has a lot of freshwater runoff be better or worse for growth? It would have lower salinity, but then also bring in more nutrients from land runoff. Or maybe it’s a place that’s more exposed to the open ocean? That could lack the shore-based nutrients, but maybe the phytoplankton bloom would occur earlier and provide more food for oysters farms.”

Surface oysters growing on the production array at Kodiak Island Sustainable Seaweeds, in Kodiak Alaska. (Credit: Jessica Whitney / Alaska Sea Grant).

Conclusion

Greene’s project is currently funded for two more years, and she is hopeful that they will be able to secure funding for an additional five years for a total of ten years of monitoring mariculture in the Gulf of Alaska.

Being so new, the mariculture industry—and the associated necessary monitoring—is continuing to develop as farmers and researchers work together to refine practices.

Farmers are generally open to learning more about their farms through MarRecon and modifying their practices as they try out what works and what doesn’t. This is an exciting time to be part of the industry.

As Greene explains, “There’s not really any set plans for a farm, or how to run a mariculture small business, or what’s the best way to do it. Everyone’s out there trying new things to push the industry forward and help understand what makes their farms tick.”

A sunny day on MarRecon partner farm, Simpson Bay Oyster Co. This farm is located on a protected bay in Prince William Sound near Cordova, Alaska. (Credit: Sierra Greene / University of Alaska Fairbanks)

0 comments